I post this work here primarily to keep it from disappearing into the earth before I do. I realize that it is a document from the past, both in it's content and in it's anthropological approach. Perhaps parts of it, most likely Chapter 2, describing Kipsigis social organization and kinship, and Chapter 3, describing male initiations as conducted in the 1960s, will be of interest to a few people interested in Kalenjin traditions. If you manage to read the complete work, you will be among one of the most exclusive sets of people in the world.

I conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Bomet Division (now Bomet County), Kericho, Kenya, from August 1965 through February 1968. This work is a revision of my doctoral dissertion, based on that research, completed in 1970. I was able to return to the research area for several weeks in 1972 while serving as the Field Director of the Child Development Research Unit, a joint project of Harvard University and the School of Edication, University of Nairobi. I have incorporated some updated information, particularly in Chapters 1 and 2, from that visit, along with very short stays in 1995 and 1996 while leading a summer study abroad course for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I have also augmented the original work with various illustrations, and have made minor editorial clarifications.

The name of the primary community, Kapsuswek, is a pseudonym. All of the individuals described in the work are people I knew or heard about. I have identified them with actual Kipsigis names other than their own, for example, I knew a man named Arap Chumo but he is not the person so labeled here.

More recently, there has been significant work by others on Kalenjin identity and the interaction between ethnic groups in Kenya which is the subject of Chapter 4. Quite understandably most of that work deals with the role of ethinicity in the politics of independent Kenya, a subject I do not take up here. Therefore, aside from editing, I have not changed Chapter 4 since I think it would be dishonest to retroactively revise my presentation of a history and ethnic atmosphere which formed the basis of my hypotheses. Similarly, I have retained the substance of the social analysis, and the interpretive hypotheses as originally proposed. Part II is virtually unchanged from 1970.

Those with some knowledge of Kenyan history will quickly see that my grasp of that subject was quite limited, and was based on a particularly local perspective. That, of course, is my shortcoming. But I also think it reflects the limited view of the people with whom I lived. When I started the research, my central interest was in the issues involved in ethnic identity. The Kipsigis were chosen at the suggestion of my mentor, Robert A. LeVine, because of the variations in cultural differences between the Kipsigis and the several neighboring communities. I chose to work in Bomet Division, far from the county seat and administrative center in Kericho and the adjacent thousands of acres of foreign-owned tea estates, because I was interested in understanding the traditional roots of Kipsigis identity rather than starting with the multi-ethnic encounters of post-colonial settings.

When I first went to Kenya in 1965, my research interests were along the lines anthropologists glossed as 'culture and personality' – various ways of talking about the relationship between the individual and one's social mileau and cultural beliefs and practices. I was not specifically focused on studying male initiations, though I had found John Whiting's ideas about them intriguing ever since I first hear him lecture on them when I was a sophomore in college. And, of course, from reading Peristiany (1939) and other literature, I was aware that the Kipsigis practiced initiations related to a cyclical age-set system that had become a classic topic in introductory anthropological textbooks. A few months after I first arrived, the annual cycle of male intiations started up and their significance to my research was immediately obvious. Even if I had initially been interested in a totally different subject, such as agricultural production, the initiations would have been impossible to ignore. To do so would be like doing an ethnography of a suburban American community and not noticing the Christmas season.

That my focus is on male initiations, my explanation of Kipsigis kinship is from the male point of view, and my specific illustrative instances involve men is not a product of any decision to ignore the female side of Kipsigis society; it is a result of who and what was accessible to me as a single male in his mid 20s.

As an undergraduate I had spent ten weeks in the summer of 1961 on the Pine Ridge Reservation of the Oglala Sioux Tribe. After my first year of graduate studies at the University of Chicago, I returned in the summer of 1963 intending to do a study focused on the economic impact of a small company that had located a couple worksites on the reservation. That proved to be a fruitless endeavor. I was, however, intrigued by the complexities of contested identities on the reservation, and my observations about that formed my Master's thesis.

I wanted to pursure these issues further, if possible in an context not marked by the duality and crushing dependency that permeates reservation life. I had also been long interested in Africa. When I discussed these interests with Bea Whiting, who had been my undergraduate tutor, she suggested I contact Robert LeVine, who was then in the Committee on Human Development at the University of Chicago. LeVine and Donald T. Campbell of Northwestern University were then conducting an extensive project, the Cross-Cultural Study of Ethnocentrism. That project involved survey research conducted among various ethnic comunities in Kenya regarding ethnic stereotypes.

A concern with ethnic identity, with the acquisition of self identity, leads naturally to a consideration of comparisons between one's self, one's group, and the "others." Stereotypes involve evaluations of others from a particular evaluative perspective, often based on bits of information, and are often invideous. The relevance of LeVine and Campbell's research to my interest in self identity was obvious. In focusing on Kipsigis identity it was not my intention to evaluate, much less disparage anyone by following this line of research. But in my experience during the 1960s, almost any discussion of a topic involving people from any other language community, any topic of regional or national events, was framed in terms of "tribes" or explained in terms of "tribal" interests and characteristics.

Very near the top of the list of words which anthropolgists wish they could eliminate is "tribe." It has been, and continues to be, used to refer to almost any level of social organization, which is to say it is analytically useless. Attempts to give it a specific meaning and then, using those criteria, select particular examples of societies at particular moments in history is like sifting sand. Anthropologists have written quite eloquently about "the problem of tribe" (Helm 1968) and "the illusion of tribe" (Southall (1970). Elsewhere I have tried to untangle the shifting understandings of group identity among the Kipsigis (They're Playing Our Song: Media and Ethnicity in Kenya).

If the term "tribe" had any validity when used to refer to self-governing but acephalous, preliterate societies, that application became void as such groups became subject to colonial authority. The word "tribe", however, was very generally used in Kenya even though it often had derogatory overtones coming from the colonial policies which crystallized ethnic differences into labeled categories of people who were then often set against each other. Colonial policies also produced larger regional identities (e.g. Kalenjin ) which are also frequently referred to as "tribes." And then there is "tribalism," a term which masks complex dynamics of power, privilege, and emotion under a negative veil that suggests further understanding is unnecessary. This work is an investigation of ethnic attitudes; it is not a study of the politics or economics of ongoing interethnic actions. I leave that to other authors.

I do, however, ask - and this is absolutely critical - that readers keep in mind that this work is based on observations now more than 50 years old. Over 90% of Kenya's current population was born after the time period described here. In certain places in the text I found it necessary to make minor edits to make it obvious that I was writing about the past. But it would be awkward to recast the whole work. The general solution to this problem in anthropology is to speak of the time period of the research as "The Ethnographic Present".

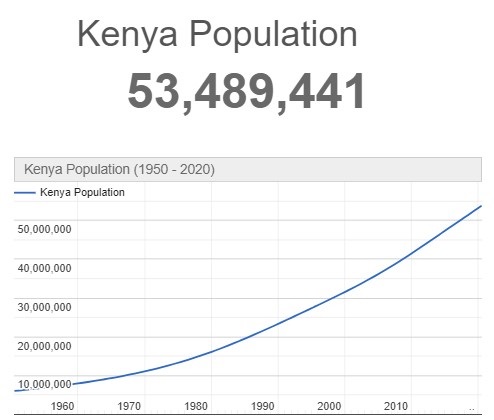

There is no country that has remained unchanged from 1965 to 2020, but the changes in Kenya have been nothing short of astounding. In Chapter 1, I present a chart of estimates of Kipsigis population from 1907 to 1969 which clearly shows exponential growth. At the time of my research, Kenya was experiencing a national population growth rate that was among the highest in the world, in essence a population explosion. In 1966 Kenya became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to adopt a national policy of birth control and family planning (Rule 1985). Needless to say, there was, and continues to be, a gap between policy and implementation, and while the national rate of increase has slowed since then, the expansion is still dramatic.

In Chapter 1, I wrote, in 1970,

That has proven to be more of an understatement than I could have imagined. If a picture is worth a thousand words, perhaps the following four pictures are worth at least four thousand. In 1966 Bomet was administratively a Divisional Center and a "trading center" that had not yet achieved the status of a town. It is now a District Headquarters and county seat. The following picture shows the main street of Bomet (there were two) in 1966 on a fairly busy day. There were a few shops on a parallel road, but this was "downtown".

Below is an aerial image of Bomet from Google Earth (downloaded in early 2020). The arrow indicates the approximate location from which the previous photo was taken.

A similar transformation has taken place in the surrounding countryside. The first image below is a rather poor reproduction of one frame of a series of aerial photographs taken by the Survey of Kenya in 1966. The original was, of course, in sharp focus and showed fine detail — my apologies to the reader for the quailty of the reproduction.

The second photo is an image of the same area which I downloaded from Google Earth in January 2020. I presume it is within the last year or so. The difference in date between them is thus a bit over fifty years.

Finally, I can do no better than borrow the words of another author, Thomas Looney, from the Preface of a work just over a hundred years old, on quite a different subject ("Shakespeare" Identified ), written in a style more eloquent than my owm:

"Truth" may suit Looney's investigation but is too sharp a word for the goals of cultural interpretation. It would be far more accurate to describe anthropology as a struggle for "pattern recognition." That term, of course, immediately draws attention to the inherent problems of perception and subjectivity which characterize all ethnographies. I have tried to report what I have heard and what I've seen and experienced as best I can. No doubt there are errors in this work at all levels, and other ways to explain what I describe when seen from other points of view. I have tried to use the analytical insights of my mentors to explain patterns of behavior that intrigued me. And I have tried to test my ideas with systematically collected data, using both questions and tools adopted by others and using questions concerning men's childhood and initiation experiences, based on my own ethnographic inquiries.

I started my fieldwork in Kenya shortly before my 25th birthday. I was 27 at the end of this period of long-term research. As a foreign guest I was granted respect beyond my years and position in life. Because of the traditional social divisions of Kipsigis society, I spent most of my time with heads of homesteads: middle aged and older men, in a word elders (boisiek, those who decide ). I am acutely aware that so many of the people who befriended me now survive only in the memories of their families. I hope that this work can repay some small part of the respect and generosity they gave me.