MEASURES OF RELATIVE MASCULINITY

This chapter presents a variety of attempts to measure the sample members on the overall dimension of “relative masculinity." The measures are arranged in three groups, test measures, general behavioral measures, and initiation measures, proceeding in general from those designed to be of universal applicability to those dealing with specific aspects of Kipsigis conditions.

The concept of relative masculinity encompasses a variety of ideas that may or may not be congruent one with the other. Different measures deal with different levels of personality and can be expected to yield different "scores" of relative masculinity on the same sample. All of the sample members, of course, have been defined by their initiations as men, all now occupy masculine roles in their communities, all think of themselves consciously as man, and all are masculine in the most obvious, overt aspects of their behavior. They show great variation, however, in the extent to which their personal behavior approximates ideal definitions of male roles, as well as in behavioral patterns not considered by the Kipsigis to be obvious markers of masculinity.

When discussing sex identity on a latent or subconscious level, measurement becomes problematic, and it is recognized that in an hour and a half interview (no matter how skillfully _ conducted) one cannot attach complete confidence to any The many measures of relative masculinity used here are something like a series of shotgun blasts at a target that is neither precisely defined nor well illuminated, and quite possibly not totally coherent. It was not expected that all of the measures would be "hits," that those which were "hits" would be measuring precisely the same dimension, or that in each case it would be clear exactly what was being measured. Rather, it was hoped that several measures would demonstrate by their combined results as much as by their individual merits that there is "something there."

Just what is meant conceptually by relative masculinity has been left intentionally vague. The study was not intended to be an original exploration of the complexities of the concepts of father salience, sex identity, and ethnocentrism, and it was not expected that the crude measures used in the field would supply the detail necessary for further conceptual clarifications of this sort. The aim was to demonstrate possible relationships between certain patterns of personality development and expressive aspects of culture in one society, despite the conceptual vagueness that currently exists.

All this having been said, I will try to state briefly what I think is implied in the dimension I have labeled relative masculinity.

Clearly the first meaning of masculinity implies a contrast with femininity, that which is characteristic of men as opposed to that which is characteristic of women. As many have noted such differences may be species—wide or particular to the sex roles of one society, and the interaction of these two levels has been a subject of much debate. This issue lies beyond the scope of this research, though obviously of direct relevance to it. In one sense, one can speak of a Kipsigis man as being relatively less masculine if his behavior in some particular situation is more like the typical behavior of Kipsigis women than the typical behavior of Kipsigis men.

Just as clearly, some aspects of masculinity do not stand in direct opposition to femininity. The biological functions of the two sexes, and the interaction patterns that they determine, are complementary but not symmetrically opposed. Stating that one should wait a year before resuming sexual relations with a wife who has borne a child is interpreted below as a less masculine response that favoring an interval of four months, but it is not exactly a feminine response.

It should also be noted that the variables discussed in this chapter have been referred to as relative masculinity, sex identity, and cross-sex anxiety. This last term implies an inconsistency between different aspects of one's identity that causes psychological stress within the individual and/or behavior that somehow deviates from the cultural norms (including overcompensation or "protest masculinity" [B. Whiting 1965]). Anxiety, stress, and deviant behavior are perhaps too extreme a set of terms to apply where all of the men in the sample are coping adequately with the psychic and social demands of Kipsigis manhood. "Cross-sex anxiety“ in this instance is probably better understood as a dynamic tension focused on the issue of sex differences. This tension, far from being debilitating or conducive to deviant behavior (as might be suggested by the word anxiety), may serve in an integrated personality as a driving force for achievement in some highly valued roles, e.g., serving as an instructor of male initiates. Thus for most of the measures described below, the subjects are being scored, not simply on the degree to which they are like men or like women, but the degree to which they are sensitive to the duality of gender in themselves and others. The use of the labels "masculine" and "feminine" is an inaccuracy preserved out of lack of more suitable terminology.

Empirically, any test can be interpreted as a measure of relative masculinity for a sample of males if the results show a significant difference, along one dimension, between the mean scores of comparable male and female samples drawn from one population, and also show variation in the responses of those male subjects. If the results are so patterned, one can compare the scores of individual males in terms of relative masculinity defined as the extent to which an individual scores as other males do or as women do on the test.

Demonstrating that the results pattern according to sex is spoken of as validating the test and involves a few problems. Obviously, the male and female samples used must be shown to be comparable on characteristics that may be suspected of influencing the test results, and that are not intrinsically related to sex differences. A difference between the mean scores for a sample of young girls and a sample of old men, for example, could be due to either sex, or age, or both. The situation becomes more problematical when the two samples differ on an important variable, such as education, because of real differences within the society in the educational levels of the two sexes. In such a case separate calculations must be made to control for the effect of education on the test scores. Secondly, the female sample must be drawn from the same social and cultural unit as the male sample, i.e., the sex difference in the results must be validated within the culture in which the test is used as a measure of relative masculinity. If the inquiry is to be limited to one culture, any number of measures can be derived that may yield significant male/female differences and can then, following the above logic, be used as measures of relative masculinity. These measures, however, may reflect cultural definitions of differences between male and female behavior patterns for the particular culture in question, and if applied to another culture, may reveal no significant sex difference or possibly differences in the reverse direction. An example of such a measure might be the degree of participation in agricultural activities by sex, which we know varies widely in Africa.

It is not essential for the interpretation of the results of the test within one culture to demonstrate that the sex differences obtained also hold beyond that culture. But if it can be shown that the measure being used does yield significant sex differences across a range of cultures this clearly suggests that the test measures something more intrinsic, more basic to sex differences per se.

The Triads Test and the Design Completion Test discussed below (in addition to other tests not included in the present study) were administered to samples of boys, girls, and women drawn from the same area in Taruswa as my sample (many of the subjects being from the same households as the subjects in the present study). These tests were administered by Jane F. Martin as part of the Child Development Research Unit directed by John Whiting. I am indebted to them for the results presented here. In all, sixty-one females were tested, thirty—three girls ranging in age from five to sixteen years old, and twenty—eight women age sixteen to fifty-eight. Also twenty—eight boys age six to sixteen and twenty-two young men age fourteen to nineteen were tested. The scores for the adult male sample in the present study will be compared with that sector of the female sample which is most comparable, that is those women twenty years old and over who are married. In all there were twenty—three such women.

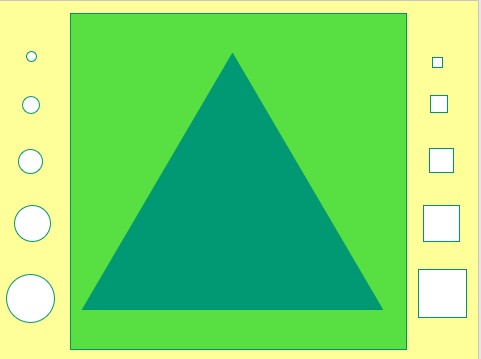

Sketch of Triads Test Materials

and A Typical Presentation

The test therefore involved making a choice between discriminating by size or by shape (e.g., which two in the example shown are alike?). A system of scoring of values assigned to each possible choice (based on the degree of difference of sizes involved) for each triad yielded one final score (on a scale from +40 to -48) indicating the degree to which a subject discriminated by size or by shape.

The hypothesis associated with the Triads Test is that men concerned with their own sex identity will show a tendency to make discriminations based on shape (symbolic of sex in the sense of gender), as will women who are hypothesized to be more attuned to such distinctions, while those men with a positive masculine identity, and hence less concern in making identifications in this way, will show a tendency to discriminate according to size (representing a concern with status, age, power, etc.).

A comparison of the mean scores for the fifty-eight male subjects and the twenty—three female subjects shows a difference in the predicted direction, i.e., the women as a group tended to discriminate by shape rather than by size more than the men (for a test of the difference between the two means t = 1.63; for a fourfold contingency table split at the total median x2 = 1.70; in either case p < .10, one-tailed test). While this difference is not statistically strong, I feel it is sufficient (considering the limits of the validation procedure) to justify the use of the Triads Test as a measure of relative masculinity.

The Design Completion Test

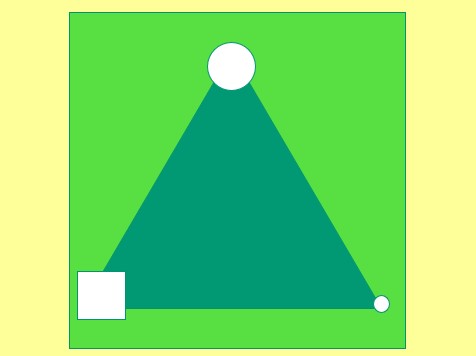

Sketch of Two Stumulus Boards

With Possible Response Pieces

The assumption behind this test is that the designs produced would reveal something about the personality of the subject, and that in particular the responses, as coded here, would show differences between male and female subjects. This test follows Franck (Franck and Rosen 1949) who first studied differences in the designs produced by male and females with a test involving thirty—six simple shapes that the subject was asked to incorporate into a completed design.

Research findings suggested that males and females differed with respect to several scorable dimensions, including the degree of slant in the drawings, the amount of closing off of shapes, underlining, the number of figures, internal elaboration of the stimulus, blunting, and whether the design was oriented up or down. Although the Franck test does not systematically correlate highly with other tests of masculinity—femininity, its power to discriminate has been tested in several research studies, and it has proved a valuable research instrument (Whiting and Lionells l967:1).

Franck's work was inspired by Erik Erikson's observations of differences in the way American boys and girls selected toys and arranged them in a defined play-space (1951). A typical response among the boys was to build up a tower of blocks and then knock it down, while girls typically arranged dolls, doll furniture, and other toys in closed circles. The assumption underlying the Franck test was that drawings represent a covert or latent representation of sexual identification expressed through body imagery.2

The Design Completion Test is an attempt to develop a measure utilizing the Franck findings in a way that can be administered cross—culturally and does not presumedexterity with writing implements, and is in a form that involves simple and reliable coding procedures.

The designs produced by the Kipsigis male sample were coded independently by Marylou Lionells and Jane P. Martin. The reliability between coders and approximately ninety-five per cent.

It was hypothesized that designs showing external elaboration and/or extension of the stimuli would be typically male responses

The Design Completion Test

Sketch of Two Responses

Showing Stimulus Extension

and designs showing internal elaboration, closure, or reduplication of the stimuli would be typically female responses.

The Design Completion Test

Sketch of Two Responses

Showing Closure and Internal Elaboration

The dimension used here is based on the coded scores comparing the number of "masculine" responses with the number of "feminine" responses.

A comparison of the scores for the fifty-eight male subjects and the twenty-three female subjects shows the predicted pattern: on the average the women made fewer designs involving extensions and more designs involving internal elaboration than did the men. The difference in the mean scores for each sex on extensions minus internal elaborations is significant (t = 2.13; p <.025, one-tailed test), and can be considered empirical justification for using this test as a measure of relative masculinity.

As part of the larger research schedule of CDRU the Design Completion Test was administered to over four hundred subjects in seven different communities in Kenya representing several ethnic groups. Similar differences, for a variety of response characteristics, have been found "between the designs constructed by males and females in each of the panel communities" (Whiting and Whiting 1970:16).

Two other test measures were included in the interviews. The first, an evaluation of age—sex terms based on Osgood's semantic differential technique (adopted from D'Andrade 1966b, see also D'Andrade 1973), did not produce statistically significant correlations with other measures. The second test asked subjects which of a series of age-sex roles (three male and three female) they would prefer for themselves. They were then asked for their second choice, third, etc. Many subjects showed confusion about making such hypothetical choices, and a large number refused to do so when only female roles remained to be selected. In many cases it was necessary for the interpreter to explain the task at some length and it was obvious to us that subjects were seeking cues from us to a much greater extent than in any other part of the interviews. After several interviews had occurred I found it necessary to ask the interpreter not to press subjects too hard as refusals were unavoidable and could be considered valid responses. Apparently, a change in the expectations of the interviewing team was unconsciously communicated to later subjects, for when the responses for the first half of the sample are compared to those for the second half, the number of refusals increases significantly (no other variable shows a significant difference when the two halves of the sample are compared in this manner). This measure has therefore been eliminated from further analysis.

The extent to which the specific interpretations given to the results of the above mentioned tests are valid, depends largely on the power of the rationale underlying these tests to predict those other measures with which they will and will not be correlated.

This section describes a series of measures based on the subjects‘ reported participation in and attitudes toward behavior patterns associated with sex-specific roles. In one way or another, questions in this section attempt to measure the degree of anxiety a subject may have concerning his sex identity. The measures deal with different levels of behavior and awareness. What they share in common is a consistent and, I hope, obvious and logical connection between the nature of the behavior in question and they most reasonable interpretation to be made about that behavior. They are attempts to develop measures with what is known as face validity.

While the psychological mechanisms leading to male pregnancy symptoms are not fully understood, the Munroes have demonstrated their association with father—absence during childhood for an American sample (R. H. Munroe et al. 1966) and with mother—child (father—absent) household during childhood for a sample of Black Caribs in British Honduras (Munroe and Munroe 1966). The theory of the development of cross—sex identity hypothesizes that the lack of a father or effective father figure during the early years of a boy's life leads to a situation in which the boy will identify to some degree with the available (female) models. It is further hypothesized that this feminine aspect of his identity, if not resolved in adolescence, will be expressed during his wife's pregnancies, a period of obvious feminine significance. Munroe and Munroe (1973) present the argument in detail, comparing the data on male pregnancy symptoms from my interviews with that from three other Kenyan groups (see also Munroe and Munroe 1971, Munroe, Munroe and Whiting 1973, Munroe, Munroe and Nerlove 1973).

The specific questions dealing with male pregnancy symptoms started with an introduction explaining that such things occurred in many cultures, including my own. The subject was then asked specifically about a series of possible symptoms and, if the reply was positive, for which of his wife's (wives') pregnancies this occurred. Subjects who reported symptoms were asked what they thought caused them. Many reported not knowing the cause. Some of the remarks which were made were as follows:

- I was worried. (About the woman or the child?) Mostly about the woman.

- I thought my blood supply was diminished because it was taken from me to form another human being.

- It was caused by doing a lot of work.

- On just hears from time to time about someone who has impregnated a woman being lazy.

- Having a child uses part of me, thus causing fatigue (this subject also reported nausea and food cravings).

- It is caused by something to do with my blood, because I touched the woman (no further explanation).

- It was caused by the beginning of childbearing (symptoms during wife's first pregnancy only).

- I was sick because the children were being born.

- When someone is frequently sleepy it is because he has impregnated a woman.

- Your blood is being drawn off to form another man.

- My blood pressure becomes high and my pulse increases. Food cravings and fatigue are due to the increased body heat caused by loss of blood to make a new person.

- Your blood is working; it is lessened by sleeping with the woman.

- I've heard that when a woman is pregnant with a boy the man grows thin.

In addition to these questions concerning the subjects, information was also collected from each subject on the history of pregnancies of each of his wives. The data collected include the following for each pregnancy: whether the woman experienced a difficult delivery, whether the pregnancy resulted in a live birth or not, if a live birth the sex of the child, and whether the child was surviving or the age at death. It was also recorded if the woman felt sick during each pregnancy, what the symptoms were and for which pregnancy, whether she experienced any food cravings, for which food stuff and which pregnancy, and whether the subject would describe her behavior as calm or upset during pregnancy. Because of the problems of determining women's ages, especially for the junior wives of polygynous men, the subject was also asked to estimate the age of the oldest and youngest surviving children and whether he expected his wife to experience further pregnancies.

A variety of explanations have been offered for the occurrence of male pregnancy symptoms. Some of them are:

(i) The man feels sick because he sympathetically identifies with the woman's difficulties at the time and not because of any deeper aspect of his identity. If this were true, one would expect some correspondence between the pattern of pregnancies for which the woman felt symptoms and those for which the nature of their symptoms (e.g., parallel food cravings). No such systematic correspondences exist in the data from the Kipsigis sample.

(ii) The man's symptoms are caused by repressed guilt over the difficulties the woman is experiencing, or the unborn child is suffering, as a result of his actions. If this were true one would expect that the pregnancies during which the husbands felt symptoms would be those during which the wives were reported to be sick, or alternately would correspond to some or all of the pregnancies following those ending in a difficult or unsuccessful birth. No such s44ystematic correspondences exist in the data. (iii) The man's symptoms are caused by repressed guilt over the realization brought on by observing his wife that his mother suffered during his development and birth. If this were true, these men who44se mothers did have definite difficulties would be more likely to experience symptoms. Subjects were asked if they had heard if their mothers had any difficulties, and if so who had told them. This question did not elicit many definite answers: six men said they had heard that their mothers had had no difficulties with their own births, four reported that they knew of specific difficulties (including one man whose mother died during his birth), and forty—eight replied that they did not know. Clearly the question was poorly phrased. However, one of the men remarked "I don't know, but she must have felt weak when pregnant and had labor pains when I was born." This suggests a slightly different interpretation of the responses: the assumption is made that all men will recognize that what this one man said is true but that those men with guilt over their mother's pain and thus those men most likely to experience symptoms if this hypothesis is true, will be more likely to avoid expressing this realization on an open conscious level. The results, when interpreted in this way, are suggestive:

| Defensive Response "Don't Know" |

Realistic Response "Yes", "No", "Presumably So" |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced Male Pregnancy Symptoms | Yes | 30 | 2 |

| No | 17 | 9 |

(iv) the man's symptoms are due to repressed aggressive feelings (hostility) toward the unborn child that is a transference of earlier feelings felt when the subject was replaced by a younger sibling as the primary object 0 his mother's attention. If this were true, one would expect that those men who were the last born in their natal families not to have symptoms, and perhaps the disappointment at being replaced could be considered strongest for first born children and that symptoms than those men who were middle children. However, no relationship exists between the occurrence of male pregnancy symptoms among subjects and their birth order among siblings.

As discussed below, the pattern of male pregnancy symptoms does correlate with other measures, notable father-absence, as predicted by the hypotheses based on the concept of sex identity.

The comparison of birth order among siblings and the responses to the question mother's bed, do not show any relationship, as might be expected if the responses to this question were based on differential sleeping patterns for either the first born or the last born of a family.

In general there is very little contact between Kipsigis men and children. The only regularized pattern I observed was between men and children who were learning to verbalize. Many men enjoyed engaging such children in word play, repeating greetings, asking the child his name, asking the child the man's name, etc. Older boys tend to gravitate to the edges of men's groups in preference to the area immediately in front of their mother‘s house with its attendant chores of helping the mother with domestic tasks and serving as a baby sitter (particularly if there is no suitable older sister in the family). In doing this, however, the boys remain silent and can be expected to be called on to perform a variety of errands for the men that they might avoid if they were elsewhere. The only times I observed a man holding a small child in his arms were when either the child or the mother was sick.

f It was also recognized that this measure might reveal not a care. Many men had described to me how in their childhood the old men refused to touch children and would only "hand" food to a child by placing it on the instep of their food and extending the leg to the child. There are also cultural restrictions against a child touching a man's eating utensils (though this has been eased among the younger men) and in generally keeping his distance from the man's bed and the man himself.

Subjects were asked four questions concerning child care. If the response was yes, they were asked if they did the task in question only when the mother was busy and unavailable, or also when the mother was not busy and could have done the task herself. The first response was scored l, and the second 2. A negative response was scored 0. The question were: When your children were small, about a year old:

- Did you feed the young child?

- Did you dress the young child?

- Did you play with the young child?

- Did you bathe the young child?

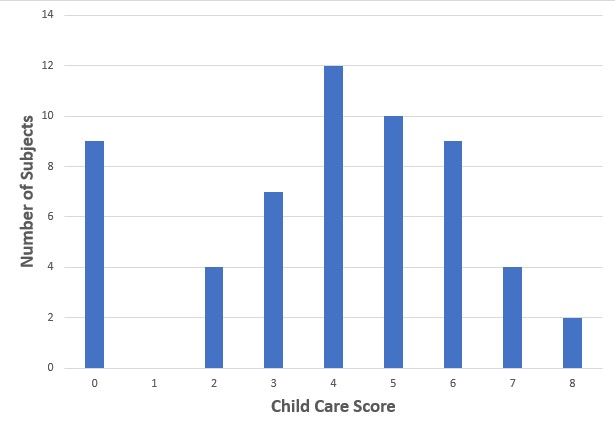

Distribution of Scores on Child Care Measure

N = 57 (Not applicable for one subject, wife in first pregnancy)

Subjects were asked about taboos relating to sexual behavior with pregnant women and women who have recently given birth, as well as about taboos relating to a man's behavior during his wife's pregnancy.

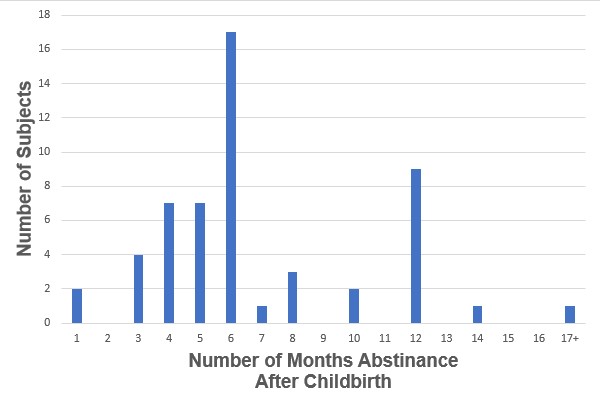

The responses on this item (referred to as PPST) suggest that this variable could be dichotomized at nine months and preserve a meaningful distinction between those subjects who reported longer or shorter periods.

Reported Length of Post-Partum Sex Taboo

N = 54

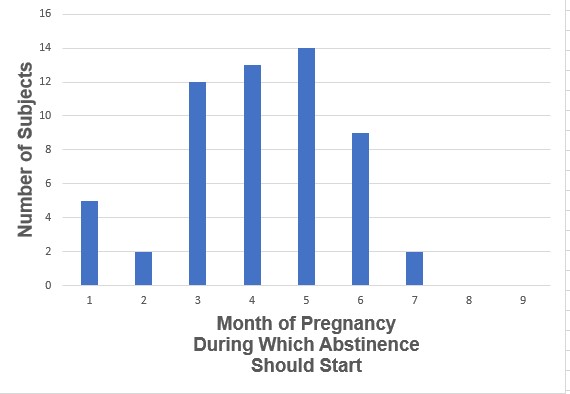

Pregnancy Taboo

N = 57

For both the post-partum taboo and the pregnancy taboo subjects were asked why they felt a man should abstain for as long as they had said, and what would happen if these periods were not observed. These question were designed to reveal the direction of perceived anxiety (hostility) if these taboos were broken. The responses, however, were highly standardized and therefore not useful in making distinctions between individuals. In both cases the most commonly reported danger was for the child. Similarly the questions on the importance of the taboos, and the subjects‘ belief in the reasons for them, were almost all answered in the affirmative and are therefore not useful for testing individual differences.

| Remembers Mother's Bed |

Does Not Remember |

|

|---|---|---|

| PPST Longer ThanNine Months | 8 | 5 |

| PPST Shorter ThanNine Months | 17 | 30 |

In a few instances, the pattern of responses on these measures are explicable in terms of some of the control variables (discussed below). In general, however, the lack of intercorrelations among these measures is contrary to expectations, and must be considered disappointing.

Data on the subjects‘ fathers‘ activities during the subjects‘ initiations were collected, as well as similar data on subjects‘ activities during their sons‘ initiations. A few universal duties appear quite clearly. Almost everyone attends his own son's circumcision. Only two fathers of subjects, among those living at the time, did not attend the operation, one of them because the subject in question had joined the initiates without his father's knowledge. A similar pattern is seen among the subjects‘ responses concerning their own sons. As one put it "I never go to see initiations, except in the case of my own child when I'm compelled to go." All fathers of subjects who were living at the time visited their sons in seclusion at least once.

Of the fifty fathers of subjects who were alive when at least one of their children (male or female) reached initiation age, thirty-three fed initiates from their houses, i.e., served as kwanda (plus one widowed mother who fed girls). Also, twenty of the twenty—five subjects with initiated children have fed initiates at least once. Three subjects explained that their clans (Kaptuiyek, Kabarangwek, and Kaborowek) did not feed initiates, though for Kabarangwek this was contradicted by three others of the clan. One man reported that his clan (Kamochilek) fed only female initiates. A clansman gave data consistent with this. Only four subjects and seven fathers of subjects had served in one of the four official roles in the rituals. Data on the less formal aspects of participation appear to offer better chances for constructing useful measures.

- Have initiations changed since the arrival of the Europeans?

- Do you think the men circumcised in the hospitals have really undergone initiations?

- Do you think the Kipsigis will abandon traditional initiations?

- Do you think they should?

- have changed 30

- hospital initiates OK 29

- will change to some extent 19

- should change to some extent 17

| 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Have Changed | .07 | .37** | .08 |

| 2. Hospital Initiates OK | .33** | .49** | |

| 4/ Should Change | .56** |

Subjects were asked if they thought their own initiation experience were harder or easier than those of most Kipsigis men. It was hypothesized that subjects with cross-sex anxiety would respond defensively, claiming that their initiations were easy (not involving stress). Thirty-four men said that their initiations were easy, twenty-two said that theirs were about the same as everyone else's or harder (two subjects did not give a direct answer).

Only three significant correlations were found among the ten possible comparisons of these measures. The men who assisted in preparing the ordeals for the initiates also tended to be those who took part in physically beating initiates (phi = .30, p = .0224, one-tailed test). Those who assisted in ordeals also tended to ne more conservative about initiations (phi = .26, p = .0459, one-tailed test). More interesting the men who were conservative tended to report their own initiations as having been easy (phi = .26, p < .05, one-tailed test).

A comparison of the two test measures and the six general behavioral measures shows three significant associations. Most importantly, the presence of male pregnancy symptoms is associated with "feminine" scores on both of the test measures:

| Triads (dichotomized) |

Experienced Symptoms |

No Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Shape | 21 | 8 |

| Size | 11 | 18 |

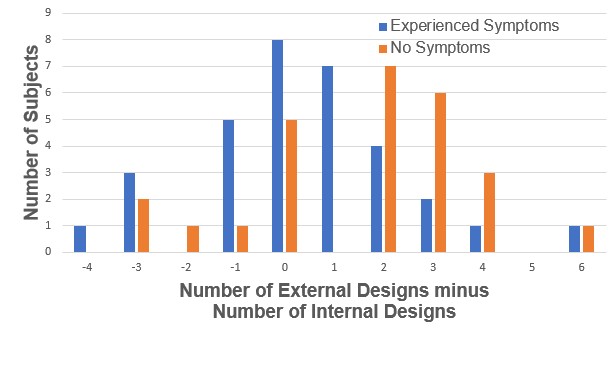

Design Completion and Male Pregnancy Symptoms

N = 58, rpbi = .27, p < .025 one-tailed test

The other significant association was between length of post-partum sex taboo and the score on the Design Completion Test. Those men who reported that the PPST should be observed for more than nine months tended to make designs involving more internal elaborations and fewer extensions and external elaborations (rpbi = .30, p < .025, one-tailed test).

As shown in Table 9-9, the Triads Test scores are also significantly related to the cluster of variables: having attended school, having better language skills, and more simply, being literature. Moreover, these relationships hold, more or less, when controlled for age. In other words formal education affects this aspect of cognitive style independent of age.

| Triads Test shape/size |

Triads Test controlled for age (partial correlation) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age in Yearsyoung to old | .36** | |

| Schooling7 years to 0 | .45** | .36** |

| Language Skills scores 10 to 0 |

.36** | .25* |

| Literacy yes,semi / none |

.37** | .25* |

| Military Service some / none |

-.04 | |

| Sibling Group more boys / more girls |

-.14 | |

| Birth Order Among Sons first,only / junior |

.07 | |

| Subject's Marital Status monogamous / polygynous |

.25* | .15 |

Conversely, when the correlation between the Triads Test and subject's marital status is controlled for age the relationship disappears.

Age in years is significantly correlated with a lower score on child care, i.e., the younger men report greater participation in child care activities (r = .40, p < .001, one-tailed test). Significant correlations also appear between a high score on child care and the variables schooling, language skills, and literacy. These relationships do not hold, however, when controlled for age. These results appear to support the common observation heard among the Kipsigis that the social distance maintained between fathers and young children has been relaxed considerably in recent decades.

The other correlation between a control variable and a behavioral measure involves the influence of age on the mention of a taboo restricting an expectant father. As one would suspect, the younger men indicated significantly less knowledge of such taboos: (rpbi = .26, p .05 two tailed test).

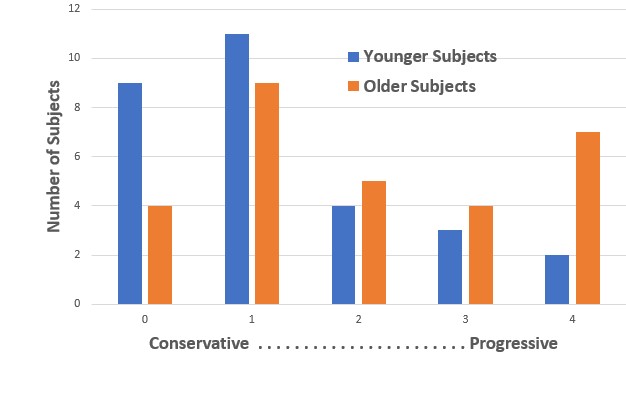

Age is also associated with the combined measure of conservatism regarding initiations. But here, the result is the reverse of expectations:

Age and Initiation Conservatism

N = 58, rpbi = .37, p < .01 two-tailed test

The interpretation of this finding is not clear. It may mean that the older men, having seen much more of the actual changes that have taken place, are more resigned to such change. On the other hand one might speculate that the younger men, being less removed from their own initiations, and being more involved in building their own statuses in the community, are less willing to see that initiations are, will be, or should be anything less than what they have always been.

2 Considering the results from several Kenyan samples that show consistent sex differences on a number of design characteristics (number of elements, direction of addition to stimulus, symmetry, etc.), B. Whiting suggested that the designs should be interpreted as reflections of adult role requirements: men's tasks involving "long-term complex plans" and women's tasks being "short-term and repetitive" (Whiting and Whiting 1970:16). For the design characteristic used here, internal vs. external elaborations, body imagery still seems to me to be the most plausible interpretation.

3 Several alternate terms have been suggested for these phenomena. Newman proposed the terms social couvade (deliberate, sanctioned) and psychosomatic couvade (unconsciously motivated and unsanctioned). Polgar suggested the term Mitleiden (suffering along) for the second type of behavior (Newman 1966:153-154). This, however, seems to imply parallels between the symptoms experienced by the pregnant woman and by her husband which are not found in the Kipsigis data. Male pregnancy symptoms seems to me to be the simplest label.