THE INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

There are two basic independent variables in this study: father salience during the subject's childhood, and the relataive severity of the individual subject's initiation experiences. These are considered to be antecedent factors within the life histories of the individual subjects which have influenced later personality characteristics, specifically sex identity and ethnocentric rigidity. The measures of father salience deal with variations in the general pattern of family organization discussed in Chapter 2. The measures of initiation experiences deal with variations in the subjects' participation in the initiation rites described in Chaper 3.

In this chapter, and those that follow, the influence of the control variables on particular measures will be discussed where appropriate.

"Father" here means the subject's pater. A man born of a leviratic union is considered to have had a father-absent childhood. Eleven fathers of subjects died before the subjects were ten years old. In eight cases the widowed mother was formally assigned a leviratic husband-surrogate (kipkondit). In only one case, however, did the kipkondit take up residence with the widowed mother.

"Presence" does not necessarily mean the physical presence of the pater at the subject's childhood home every day, but rather the effective social presence of the father as a member of the homestead. A subject was thus considered to have had a father-present childhood if, for example, his father regularly divided his time between the subject's mother's household and another wife's household.

The scoring of this measure was based on responses to a number of questions concerning the subject's natal family during childhood. Because of the primary importance of this variable to the hypotheses, these questions occurred early in the interviews, following naturally upon the common conversational questions of parents' names, home area, etc. This was also the first measure scored at the start of the analysis.

A number of other measures were constructed in the attempt to estimate the realtive influence of paternal and maternal figures upon the subject as a child. Although these did not prove as useful in the subsequent analysis as the direct estimate of father-absence, three will be discussed briefly.1

The scores on the variable father-absence proved to be unrelated to scores on these three other measures.

The above measures, based on structural features of the subject's natal family, are obviously very crude indicators of the quality and quantity of interaction which a subject experienced with his parents. They are, however, not greatly distorted by memory or present personality characteristics. In addition, more direct indicators of childhood experiences were sought through questions dealing with memories of punishment and protection by each parent, estimates of parental favoritism, and so forth. Not surprisingly, these data have not produced significant correlations with other variables. It is, or course, a real problem whether such data should be considered as measures of childhood experiences or measures of selective distortion caused by current personality characteristics.

| Many Beatings | Few or No Beatings | |

|---|---|---|

| Relatively Long Seclusion |

24 | 5 |

| Relatively Short Seclusion |

17 | 12 |

If the subjects' responses on this question were a reflection of objective events, one would expect a relationship between the amount of beating reported and the absolute length of seclusion in months. But no such relationship was found. These two results, taken together, imply that the length of seclusion relative to one's age-set measures the severity of initiation in the sense most relevant to the hypotheses, i.e. severity as perceived by those being initiated.

The second correlation among the various measures of initiation experiences is shown in Table 8-2. Again, with age at initiation, the relative measure rather than the absolute one yields a statistically significant association.

| Relative Length | of Seclusion | ||

| Long | Short | ||

| Older | 10 | 2 | |

| Age at initiation relative tomenjo mates |

Same/Middle | 10 | 18 |

| Younger | 9 | 9 |

The association of these two variables, each of which was expected on the basis of remarks made by informants to be useful measures of the perceived severity of initiation, led to the construction of a combined measure of the relative severity of initiation. This was done by dividing the sample between those cases indicated in red from those indicated in blue in Table 8-2. Thus a subject was considered to have undergone a relatively severe initiation if he was older than most of the other boys in his group, or if of the same age as the others, if his group was secluded for a longer period than most of the initiation groups in his age-set (22 cases), and to have undergone a relatively easy initiation if younger, or if of the same age, if secluded for a relatively shorter period (36 cases).

Further data on the subjects' reactions to, and opinions of, initiation rites are discussed in Chapter 9 as measures of personality characteristics.

No significant relationship exists between any of the measures of father salience and any of the measures of severity of initiation. In other words, the two variables considered conceptually to be the independent variables in the subsequent analysis are also statistically independent of each other. For father-absence and the combined measure of relative severity of initiation the correlation coefficient r = .03.

and the Independent Variables

Subject's age was found to be related to father's marital status during the subject's first ten years (Table 8-3). The older subjects tended to have (had) polygynously married fathers, the younger subjects monogamously married fathers.

| Father's Marital | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Polygynous | Monogamous | ||

| Subject's Age | Old | 22 | 7 |

| (dichotomized) | Young | 13 | 16 |

If one assumes that the average difference in ages of fathers and sons has not changed significantly over recent generations (i.e. the older subjects were not born later in their fathers' life cycles), this finding might be considered as indirect evidence of a decline in the rate of polygyny. A very similar relationship exists between subject's age and the parental ratio measure, which is a slightly different coding of the same data on the father's marital status (phi = .27, p = .037, two-tailed test).

The other two correlations between a control variable and a measure of father salience are of much greater importance to the basic hypotheses. The correlation coefficient between father-absence and subject's age is r = .24. This relationship was not predicted, and does no relate to the reasoning behind the basic hypotheses, and therefore a two-tailed test of significance is appropriate, in which case the strength of the correlation does not attain the usually recognized level of statistical significance (p < .05). Nonetheless, because this relationship is not easily explicable, and because subject's age is the most direct measure of the great changes that have taken place among the Kipsigis in the twentieth century, it appears wise to control for age when discussing the effect of father-absence on the dependent variables (Chapter 11).

This decision is reinforced by the other significant finding, an association between father-absence and being literate (r = .34, p < .01, two-tailed test). This finding is rather troubling since one may assume that literacy, however acquired, probably affects some of the tests of cognition used below as measures of relative masculinity, and quite possibly also one's views of other ethnic groups. Moreover, the relationship between father-absence and literacy does not disappear when controlled for age (partial correlation coefficient r = .27, p < .05, two-tailed test). Clearly attention must be given to these interrelationships when discussing the final results.

Year of Initiation and Length of Seclusion

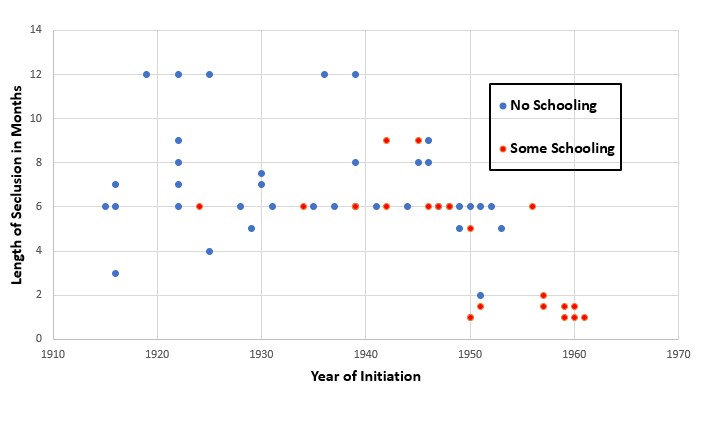

Most obvious, and perhaps most important in its implications, is the decline in the length of time spent by initiates in seclusion. The period of the initiation experience has been severely compressed. Table 8-4 shows the reported length of seclusion and the estimated (or reported) year of initiation for the 58 subjects. Even considering the large number of responses of six months, there has been a general decrease in the length of seclusion over time (r = .56). In the years just after World War II, there was a major shift from initiations lasting six or seven months to many lasting four or five weeks. This shift corresponds approximately with the start of Sawe age-set in 1946 and is closely associated with the increasing proportion of boys of initiation age attending school. The correlation coefficient for length of seclusion and year of initiation for the school group is r = .66 (p < .01, two-tailed test) and for the non-school group r = .31 (p < .05, two-tailed test). This can be seen as the result of three factors: primarily there was an expansion in the number of schools in the district, and more boys had the opportunity to attend school. Secondly, those in school have gone on further, continuing their educations to any older age, in recent years. Thirdly, though the data from the sample do not show this, the age of initiates has dropped from perhaps a median of sixteen to about thirteen today. There is universal agreement among Kipsigis men on this point. This conflict between modern education and traditional initiation, in terms of the demands on the initiate's time, became critical, and local government bylaws were passed making it an offense to seclude any male initiates during term time (since school boys readily left school to join their friends). Since the primary school year runs from mid-January to early December, the total initiation cycle has had to be compressed into six weeks around Christmas. As Table 8-4 indicates, there were attempts in the early 1950s to segregate the school boys from the others and to hold initiations of different durations in the same year. This, however, proved unworkable, thought the same pattern of dual initiations, one of several months and one compressed into the school holidays, was still being practiced for female initiates at the time of this research (1965-1968), since very few girls of initiation age (about fifteen or sixteen) were in school.

The sharp decline in the length of seclusion for males has necessitated certain abbreviations in the scheduling of the stages of initiation. Since the period of recuperation following the operation cannot be shortened, the later stages have been greatly compressed. Where once the boys hunted a great deal, they now spend a few weeks at it. Similarly the period following Kayaet, when the initiates wear the marangochek headdresses, has been dropped by almost all communities. For most groups the Kayaet ceremony is followed the next day by the Yatet ap Oret, or coming out ceremony. Quite obviously the great increase in cleared land and its enclosure have made a knowledge of hunting skills of little practical value in almost all of the district. The older men have tried to keep the formal rituals intact through all these changes, but here again education is causing some conflicts. The younger men, particularly the most educated among them, feel that such items as the instructions in supernatural manipulations during tienjinet to be little more than outdated superstitions.

Thus there is clear evidence that the severity of initiations has declined in absolute terms in recent decades. In terms of the differential effect of variation in initiation experiences, however, it seems likely that differences between generations may not be as salient to the initiates as differences in the treatment of initiates of the same generation. For this reason the combined measure of the severity of initiation experiences is based on relative age at initiation and relative length of seclusion. The measure thus constructed is partially successful in controlling for these historical changes (the correlation coefficient for subject's age in years and a relatively severe initiation is r = .21, p > .10, two-tailed test).

The combined measure of relative severity of initiation is not related to any of the other control variables, including schooling.