FROM HYPOTHESES TO QUANTIFIED DATA

The specific hypotheses presented in Part I were developed toward the end of the second year of fieldwork. While a longer field trip may yield insights not gained in shorter visits, there is no magical guarantee that these insights were valid. In this case the general theoretical arguments on which the hypotheses were developed had been subject to controversy, and the research procedure being followed during their formulation was of the type usually labelled "participant observation." This might be described as a standard, but hardly standardized, approach in which the process of data collection is underspecified and developments in the process are essentially experiential and unavoidable personal. As in everyday life, the decisions one will have to make cannot be totally anticipated nor, having arrived at a sense of meaning about a particular question, can one be totally conscious of all the steps that led to that conclusion. For these reasons I felt it necessary to devote most of the remaining several months of research time to the systematic collection of evidence bearing directly on the plausibility of the hypotheses. The method chosen was the collection of quantifiable data through standardized interviews with a sample of Kipsigis men sufficient large in number to allow tests of statistical significance.

While the experimental method appears to be a fairly clear-cut and objective way to test ideas, the validity of the results obtained in any particular study depend, by the logic of the method, on the extent to which the initial premises of the approach have not been violated. Yet the application of the method to any human situation is necessarily an exercise in compromise and approximation. The present study is marked by a number of such limitations, arising both from the situation and the ability and resources of the researcher. This chapter, therefore, discusses in some detail the processes by which the sample was generated and the interviews were conducted, as well as attempting an assessment of the sample which was obtained. Subsequent chapters present the analysis of these interview data with further comments concerning methodology when appropriate.

- Can a relationship, explicable in terms of sex identity, be demonstrated between these "formative" experiences and personality characteristics?

- Can a relationship, explicable in terms of sex identity, be demonstrated between these variables and ethnocentric attitudes?

- Basic information identifying the subject by name, residence, age-set, clan, marital status, etc.

- Data on education, language skills, and work histories,

- Data concerning the subject's natal family and childhood experiences, including various measures of father salience as well as information to test alternate hypotheses of personality development.

- Data concerning the subject's initiation experiences, including measures of initiation severity, the subject's reactions to his initiation, and his current attitudes toward, and involvement in initiations.

- Data concerning the subject's opinions on, or reported involvement in a series of behavioral patterns related to sex-role activities, including various measures of his sensitivity to the issue of sex identity as well as data to test alternate explanations for the response patterns on some of these measures.

- Data derived from various psychological tests of cognition relating to sex identity.

- Data concerning the subject's desired social distance from, and his past contact with, members of five other ethnic groups, and data on the subject's concepts of himself and members of these other groups.

A further decision was made to draw the sample from the heads of homesteads, within Itembe, and specifically, as nearly as possible, to draw the sample from men living in a continuous area that had some relation to existing social units.

Because of the hypotheses being considered and the nature of the measures used, two further restrictions were placed in the sample. First, pairs of full or half brothers were to be avoided since it was doubtful that enough pairs could be included as might be necessary to test whether they represented truly independent cases of childhood experiences. Secondly, it was decided to include only married men whose wives had experienced pregnancy (because of questions relating to pregnancy taboos and the subject's physical reactions to his wife's pregnancy). This restriction in effect placed a lower limit on the age of sample members. Finally, in those cases where both a father and son were living together, and both met the above criteria and were equally available for interviewing, preference was given to the homestead head, father-son pairs among men living on different homesteads were not avoided. Two such pairs occurred in the final sample actually interviewed.

Working from government records of the settlement of the area and from data collected earlier from the local primary school records and from genealogical interviews, a list of all the men within the chosen area was drawn up. Selection among men who were known to be siblings was made by flipping coins. The preliminary list was then checked by a local elder who had an extensive knowledge of the genealogical relationships in the sample area and a few other pairs of siblings were identified as well as a few men who were absent. Additionally, four men were eliminated for specific reasons: one who was deaf and dumb (but whose half brother was interviewed), one who was partially senile, one who was a Nandi, and one man who had refused to cooperate with my research from the beginning.

The resulting list constituted the potential sample with which the interviewing started.

As expected, a number of changes were made in the questionnaire on the basis of pretesting. Following these sessions I also consulted with John and Beatrice Whiting, in Nairobi as directors of the Child Development Research Unit.1 They made available two of the cognitive tests developed for cross-cultural research by Whiting and Lionells (referred to as the Triads Test and the Design Completion Test) which I included in the revised interview schedule. As the analysis will show, these tests were of critical value to my research.

The pretesting sessions also sought to reveal the best way for my assistant and myself to divide the tasks of interviewing. Having tried several variations, it was agreed that I would read the preamble and ask the introductory questions (in Kipsigis), record all the answers (in English) and manipulate the materials used in the psychological tests. The bulk of the questioning would be done by the assistant with only minimal interruptions, in English, if I felt a response was unclear or if the assistant had make a mistake in following one of the optional lines of questioning in the interview schedule. With minor exceptions this was the approach followed in the final interviews. There was some variation in who asked the introductory questions (which are probably those least susceptible to influence by the interviewer), but almost none during the bulk of the interviews. Regardless of the subject's linguistic skills all questions were asked in Kipsigis.

The interviews began on October 26, 1967 in the back room of a shop located approximately in the center of the sample area. An attempt was made to establish a similar atmosphere for all subjects. Initial greetings were kept brief and extraneous discussions were minimized during the course of the interviews. The goal was to create a situation different from usual Kipsigis conversations, and thus to avoid the normal conventions of politeness about what could and could not be asked and what could and could not be answered. Although all subjects were told that they could refuse to answer any questions they wished, there were scarcely any direct refusals, and very few subjects used the standard Kipsigis method of refusal, "I don't know" (m'angen) on any of the questions. Neither I no the assistant ever had the feeling that a subject was fabricating answers (which would be very atypical behavior among the Kipsigis). This feeling is supported by the fact that with several subjects for whom genealogical data had been collected a year earlier, much fuller information was elicited during the interviews and with much less difficulty. This duplication of data did not reveal discrepancies of the sort that might arise from false answers.

The course of the interviews was not, however, without its problems. It proved to be quite difficult to find as many subjects as planned, and since total participation by the original potential sample was not achieved, it is necessary to discuss these difficulties in some detail and to consider the extent to which the actual group of subjects interviewed may be a distortion of the original potential sample.

When the interviews started, large signs were posted outside the shop explaining that I wished to see the men whose names were listed (the potential sample) for approximately two hours of work for which they would be paid. The young mn working in the shop was literate, and sympathetic to my research, and spontaneously took on the chore of explaining the sign to his curious but illiterate customers. In addition, the first subject interviewed was recruited to visit other potential sample members at their homes to ask them to be interviewed.

As the interviewing proceeded, it became apparent that several members of the potential sample were no available because they were working every day outside the sample area. It also became difficult to find men who were available even though they were at home for a number of reasons. November and December area the months of plowing, and with the difficult soil conditions and ox-drawn plows used in the area, this is by far the major task in the men's annual cycle of activities. Plowing starts at dawn, stops by mid-morning with the heat of the day, and is generally followed by heavy drinking. On many other days unseasonably heavy rain made the road to the shops impassible for many hours and suppressed the general level of movement in the area.

The period of interviewing also corresponded to a tax collection campaign by the Kipsigis County Council with the assistance of national and local police. Since census records were not available, they conducted house to house checks for current tax receipts, set up road blocks, and made a series of "raids" (including one at the shops while an interview was in progress) looking for tax defaulters. Many potential subjects therefore avoided the area of the shops for some days. On those rare occasions when several subjects appeared together, it proved impossible for us to interview more than four in one day. Additionally, I lost many days due to dysentery. Suffice it to say the task of collecting data from a reasonably large sample under such conditions can prove much more difficult than anticipated.

During the course of interviewing it was decided to increase the sample area to include thirty-nine more homesteads. Information on which of these homesteads had men who met the sample criteria was not as complete as that for the original area. Only four homesteads could be definitely eliminated, though there were undoubtedly others that were not suitable. A second subject was hired to help approach men in this new area. Twenty-two men from this area were interviewed. A few others were present when the interviews were finally stopped because I had no more time. It is not clear of any of the men from this added area were not interviewed because they specifically refused to be.

All in all, sixty-one men were interviewed. Two failed to complete the last section of questions on out-group attributes, one because of fatigue, and one because the interview was interrupted by a medical emergency in the community requiring my services as an ambulance driver. When the information on father's name, father's and mother's clans, and number of father's wives was cross-referenced for all subjects, I discovered that there were two pairs of half brothers and one pair of full brothers among those interviewed. In one pair, one subject was eliminated because he was much younger, his responses contained many more blank answers than any other subject, and because it became apparent after the interview that his parents had been divorced very early in his life and that the information on that section of his life was inconsistent. In the other two cases, one member of the pair was eliminated by flipping a coin.

The remain fifty-eight men (fifty-six of whom answered the full questionnaire) can be termed the refined sample on which the various statistical analyses are based.

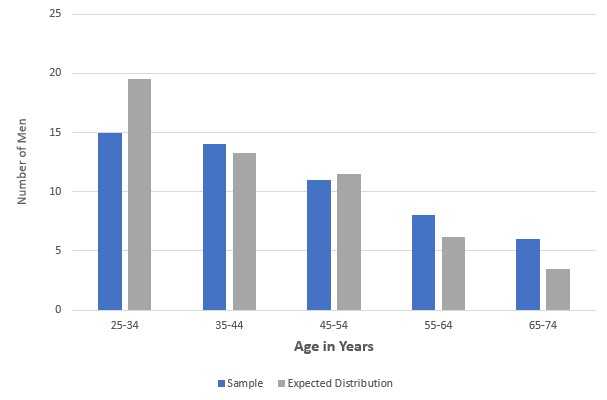

First it must be recognized that there area no data on the frequencies of distribution among the total population for most of the variables discussed here. Nevertheless, a few crude tests are possible. Ominde (1986:176) has published a diagram of the age-sex pyramid of Kipsigis in Kericho District based on the 1961 census. Table VI - 1 compares the actual age distribution of the refined sample with "expected values" based on Ominde's diagram.2

| Age in Years | Number of Subjects |

Expected Distribution* |

|---|---|---|

| **20 - 24 | 4 | |

| 25 - 34 | 15 | 19.5 |

| 35 - 44 | 14 | 13.3 |

| 45 - 54 | 11 | 11.5 |

| 55 - 64 | 8 | 6. |

| 65 - 74 | 6 | 3.5 |

| Totals | 58 | 54 |

in Kericho District (Ominde 1968:176).

** Five year interval, no subjects under age 20.

The distribution of subjects by age categories does not deviate significantly from the figures derived from these data on the total population (x2 = 3.41, p is between .40 and .50). When it is remembered that the sample was restricted to married men, and that preference was given to the older men of the homestead, (if both were present and available for interviewing), the differences between the age profile of the sample and the age characteristics of the total population become understandable. It should be remarked, however, that a disproportionate share of the Kipsigis living outside Kericho District are younger men involved in wage labor.

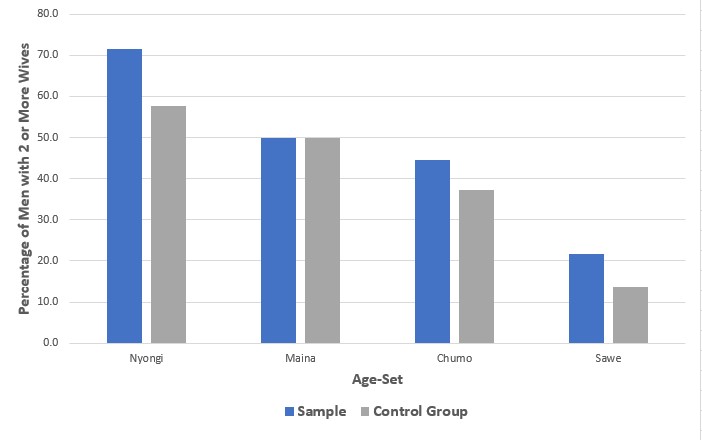

It has also been possible to check the refined sample by drawing on data from genealogical records collected separately from the interviews in the same area of Itembe. The genealogies include data on the age-set, clan, location, and number of marriages of the household head's father, brother, and brothers-in-law. From these data it is possible to construct a post hoc "control group" consisting of all the men mentioned, other than the subjects (fourteen of the sample members were included in the census of Kapsuswek, and twelve other subjects were mentioned as relatives in one or more genealogies). To this group has been added those fathers of subjects for whom data were collected during he interviews who do not otherwise occur in the genealogical records. There is no reason to believe that the composition of this "control group" is biased with relation to the topics under consideration in this study. A few comparisons can be made on the basic sociometric variables between this "control group" and the refined sample. Table 6-2 compares polygyny by age-set between the fifty-eight subjects and a group of 150 of their kinsmen, in-laws, and neighbors. The comparison strongly suggests that the sample closely represents the wider population.

| Age-Set | Total Number |

Number Monogamous |

Number Polygynous |

Percent Polygynous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Nyongi | 7 | 2 | 5 | 71.4 |

| Maina | 10 | 5 | 5 | 50.0 | |

| Chumo | 18 | 10 | 8 | 44.4 | |

| Sawe | 23 | 18 | 5 | 21.7 | |

| Totals | 58 | 35 | 23 | 39.7 | |

| Control Group | Nyongi | 33 | 14 | 19 | 57.6 |

| Maina | 30 | 15 | 15 | 50.0 | |

| Chumo | 43 | 27 | 16 | 37.2 | |

| Sawe | 44 | 38 | 6 | 13.6 | |

| Totals | 150 | 94 | 56 | 37.3 |

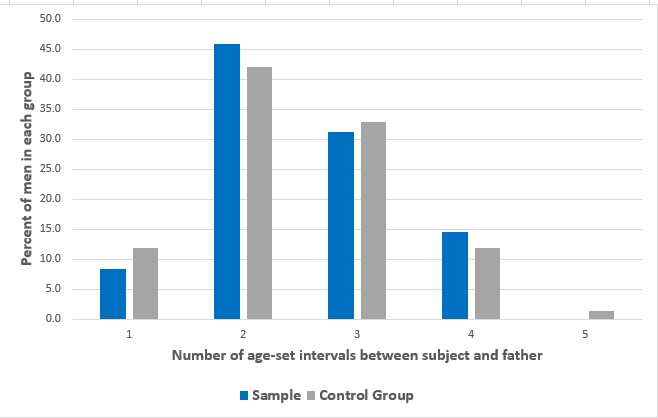

Data are also available for forty-eight subjects, and seventy-six men in the control group, to allow a comparison of the number of "age-set intervals" between the age-sets of the subjects, or control group members, and their fathers (Table 6-3). Here again there are parallel findings which tend to confirm the assumption that the interview sample is representative of the larger population.

| Sample | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Set Intervals | Number of Father-Son Pairs |

Percent | Number of Father-Son Pairs |

Percent |

| 1 | 4 | 8.3 | 9 | 11.8 |

| 2 | 22 | 45.8 | 32 | 42.1 |

| 3 | 15 | 31.3 | 25 | 32.9 |

| 4 | 7 | 14.6 | 9 | 11.8 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.3 |

For a few of the dependent variables (e.g. the Triads Test, the Design Completion Test, and the measures of ethnocentrism) there are data from other sources relevant to the findings of this study, and such data will be discussed below. Yet for most of the measures used in this study there is no reasonable way to suggest the corresponding parameters of the total population about whom inferences are to be made. Here we must review the restrictions arising out of the definition of the sample and the possible distortions caused by the failure to interview all of the potential sample, and ask how these factors may have biased the results.

First, the restriction of the sample to a small geographical area: the ecological differences mentioned in Chapter I between the sample area, which is mostly suitable for grazing, and the much more fertile hill areas within Kericho District suggest that there may be differences in the types of people who would choose to live in these areas. Within the obvious restrictions of availability of land and the problem of leaving a closely interrelated community, individual Kipsigis are free to move anywhere within their area, i.e. ownership of land and membership in a community does not depend upon an identification of land areas with prescribed statuses such as clan membership. Records of the settlement of Itembe in the 1950s reveal that while plots were given to many families then living in the area as "squatters" (and who presumably had no other place to go), a large proportion of the plot holders came from many different areas. Although a few of these original settlers have since left for the more fertile areas, there is some reason to believe that many of those who remain did not select to move to Itembe because of personality characteristics that might be related to ecological conditions. While some men quite clearly express their commitment to pastoral values and judge the area only as it is suitable for the more traditional economics, others complain that they are being frustrated by the conditions from developing more in the modern activities of cash crop farming. It is my impression that further testing would establish few, if any, significant personality differences between the sample members and their tribesmen in the higher areas.

But while ecological factors do not appear to be directly related to any gross personality differences in the various parts of the district, soil, rainfall and roads are becoming increasing important in determining the pattern of economic modernization within Kericho District, just as they are within Kenya as a whole (Soja 1968). Thus the sample members are perhaps best characterized as being less influenced by the recent changes in Kipsigis life than people in more fertile areas. The population density in Itembe is less than that of the district as a whole, the proportion of children in school is less, the amount of cash spent by a typical household is probably a bit less, etc. It is not at all clear, however, how these factors might affect the basic variables of this study, if indeed they do.

The restriction of the sample to married men des not seem to be of any significance beyond the obvious one of eliminating initiated by as yet unmarried youths. The only case of a man in the sample area without a wife was an elderly widower who was eliminated from the sample because he was senile (his mental and physical decline was related to the fact that he was living alone, but that is another matter).

Another way to consider possible biases in the sample is to look at who is not included, Some of the men originally included in the potential sample proved to be away from home working, or living at home but working outside the area every day. Some of this work involved seasonal agricultural work (plowing) for other Kipsigis, while other men were in more regular wage-earning jobs in towns. A look at the work histories of the subjects shows that ninety-seven per cent of them have worked for wages in one sense or another, though a large proportion of them (fifty-seven per cent) have only done agricultural work, in most cases o European estates as "squatters" during the colonial period. However the range of jobs is rather wide. It is doubtful, then, whether the absence of some community members at jobs means that the sample shows a bias of under-representing wage earners, particularly when it is noted that the typical pattern of employment among the Kipsigis is to work for a period of a few years in order to establish oneself as the head of a household and farm.

On the other hand, the fact that some men in the potential sample refused to be interviewed appears more serious. Although the exact number of men who refused cannot be determined, and is apparently not very large, one man openly refused and it is presumed a few others were unwilling to make themselves available. These men were unwilling to enter into the interview, an intensive confrontation with a young "European" in which they would be asked many questions and would be without the status reinforcements of a usual Kipsigis social setting. If one had to guess at the effects of these refusals on the sample, it would appear that the sample does not fully represent those who are more ill at ease with non-Kipsigis, those who are perhaps more ethnocentric than the average.

Concerning the expansion of the sample area during the interviews, it should be noted that there was no appreciable difference between the added area and the original area of the potential sample. If this change had any effect, it was perhaps to increase the number of sample members who were self-selected, though it was my impression at the time that those men who were approached in the expanded area came to the interviews and that those who did not come had not yet been approached. Undoubtedly many more men would have come if the interviews had not ended when they did.

To generalize, there are both specific data and plausible reasons for assuming the sample is representative of the people of Sot Division, and no evidence to suppose that the sample does not reflect the great majority of men, if perhaps not the most egregious types in the Kipsigis tribe as a whole.

The utility of the sample to supply data from which statements about the total tribe can be drawn relies also on the type of interpretations to be made from the data. The intent here is to investigate the interrelation of variables among individuals and not to determine the exact frequency distributions of any trait among the total population. The data are concerned with relative differences among individuals, not with estimating the percentage of all Kipsigis who would score feminine on a certain test of sex identity or in measuring the absolute intensity of an attitude toward a neighboring tribe. The nature of the sample clearly allows more confidence in making the first sort of statement, which is the purpose of this study, while the imperfections of the sample are primarily obstacles to making statements of the second sort.

2 Approximate percentages were read off of Ominde's age-sex pyramid for the five ten-year intervals shown, and these percentages were each multiplied by 54, the number of subjects in these intervals, to arrive at the expected values, i.e. to determine how 54 units would be distributed among these intervals if they followed the pattern of distribution found in the total population.