ETHNOCENTRISM AND SEX IDENTITY

In the previous chapters some of the main attitudes of Kipsigis men toward the neighboring Nandi, Maasai, Luo, Gusii, and Kikuyu have been sketched, and other aspects of the Kipsigis experience that might offer a deeper understanding of the nature of Kipsigis ethnocentrism (the basic organization of Kipsigis society, the central rituals of Kipsigis men, and the history of Kipsigis interaction with their neighbors) have been presented in some detail. In this chapter I will try to suggest how these various fields of data may be interrelated, and will try to generate more specific ideas about these interrelationships, which may then be tested. The argument is here presented in brief form, and then discussed in more detail, point by point, followed by a statement of the basic hypotheses of this study.

One of the main principles structuring Kipsigis stereotypes of the ethnic groups around them is the evaluation of those groups along some dimension of relative masculinity. Among themselves, the Kipsigis consider male initiations as the primary, necessary process by which an individual acquires the identity of manhood. When judging the masculinity of outsiders, the Kipsigis base their views primarily on whether or not the outgroup practices circumcision comparable to that of the Kipsigis. From this one criterion a whole series of conclusions are drawn concerning men of the other group. the data suggest that the motivation behind such ethnocentric applications of Kipsigis categories to outsiders is not just a desire for logical conceptual consistency, but also involves a degree of displacement of psychological tensions arising from a concern with one's own masculinity.

The persistence of these stereotypes (in terms of both their structure and the sentiments associated with them) may thus be one of the results of Kipsigis male initiations. But what, in turn, is the relationship between the initiation experience and the assumption of certain attitudes about masculinity? If we assume that initiations have some effect on the development of sex-role identity, we much also assume that this effect is limited, that there is some continuity between individual personality patterns before and after initiation. Thus some understanding of the effects of Kipsigis initiation (and perhaps ultimately of the content of Kipsigis ethnocentrism) may be found by looking at pre-initiation (childhood) experiences. Previous research in a variety of cultures suggests that the interaction patterns of the male child with other people, particularly his parents, may have a determining influence in the development of his own sex identity.

The analytical approach being used here deals with a model of individual personality development, and postulates a relationship between the conceptualizations of self and others on the level of individual though patterns. In order to test these ideas in detail, data must be collected for which the individual Kipsigis man is the unit of analysis. These data must first show variations among a sample of Kipsigis men in their childhood experiences, in their experiences during initiation, and in the degree of masculinity of their present identities. Secondly, the data must show that the neighboring ethnic groups are stereotyped along the lines described above, and that there is variation in the extent to which individuals in the sample subscribe to such stereotypes. Finally, and most importantly, it must be seen if the variations in these several areas of experience and behavior are significantly related, one to another, according to a specific set of hypotheses derived from this general analysis.

The above statement represents, in a very condensed and ordered form, the thinking behind this study as it was developed in the field. A number of points call for clarification and elaboration.

One of the main principles structuring Kipsigis stereotypes of the ethnic groups around them is the evaluation of those groups along some dimension of relative masculinity.

The point here is that the stereotypes of outgroups presented in Chapter IV are not a series of unique characterizations, each qualitatively different from the next, but that some more general patterns exist across these different stereotypes. The outgroups are compared according to how they vary (are perceived to vary) in the degree to which they possess some general qualities, and that one such quality, or dimension, deals with masculinity. Thus the Maasai are considered as being extremely masculine, the Luo as most feminine, and the Gusii, and more vaguely the Kikuyu, are seen as intermediate types. I would argue that this structuring of Kipsigis attitudes along a dimension of relative degrees of masculinity is not just an "etic" distinction introduced by the analysis, but a summary of "emic" distinctions made by the Kipsigis. This ordering of other tribes by degrees of relative masculinity emerges quite explicitly whenever Kipsigis compare the various groups around them.

Among themselves, the Kipsigis consider male initiations as the primary, necessary process by which an individual acquires the identity of manhood.

The fact that the Kipsigis consider initiation to be the process by which one becomes a man has been stressed in Chapter III. When asked if their initiations changed them, nearly half of the men interviewed said things like "Yes, I stopped being a child and became a man," "I was declared to have become a man," and "It made me truly a man." Also, I think it is clear from the description of initiations presented in Chapter III that a great deal of the symbolism used in initiations refers implicitly to the end of childhood and the assumption of manhood. By "primary, necessary process" is meant the belief that initiation is the one way to become a man.1 The acquisition of "the identity of manhood" implies both the recognition by others that the initiate has assumed a new age-sex role, that of a young man (murenik), and the change in the new initiate's self-image, the activation of those values and role models, presented to him both in initiation and before, which guide his thinking and behavior as a man.

When judging the masculinity of outsiders the Kipsigis base their views primarily on whether or not the out-group practices circumcision comparable to that of the Kipsigis. From this one criterion a whole series of conclusions are drawn concerning men of the other group.

Several illustration of Kipsigis concern about initiation among other groups have been presented in Chapter IV, along with the descriptions of how Kipsigis stereotypically characterize the tribes around them. The presence or absence of initiation is not considered as an isolated, or relatively unimportant variation (as perhaps the presence or absence of drums or ancestral names may be), but as a diagnostic trait which must have enormous implications or other aspects of the behavior patterns of the outgroup members. The Kipsigis credit initiation with a major role in teaching proper social values and personal virtues. They also believe that the dynamics of personality development, as they understand them, are not peculiarly Kipsigis. Thus they consider the presence or absence of initiation as the reason for the way their neighbors deviate from Kipsigis norms. In fact in many cases they deduce what the Maasai must be like because they are circumcised, and what the Luo must be like because they are uncircumcised.

At this point one might ask whether these Kipsigis characterizations of the other groups are not ethnocentric deductions, but conclusions based on observations of actual differences between the various groups - in other words, that they derive, not from Kipsigis categories, but from the realities of cultural diversity in the area. LeVine and Campbell's extensive survey of ethnocentrism in East Africa (LeVine 1966) focuses on this question of the reality content of stereotypes of outgroups. Using an approach which they have termed "reputational anthropology," they compared the stereotypic description of people in each society given by members of that society with the descriptions of people in the same society given by members of each of several surrounding societies. They found many instances in which the respondents from several different cultural backgrounds agreed in their characterizations of specific tribes. Such agreements strongly suggest common recognition of actual trait differences.

At first glance it appears that there are, indeed, many congruences between the stereotypes that follow deductively from Kipsigis categories and the characterizations which one might arrive at after detailed observations and comparisons of the Nandi, Maasai, Gusii, and Luo. Nor is this particularly surprising. At least to the extent that these characterizations imply expectations of how these groups will behave toward Kipsigis they must be based on some experienced reality. This was particularly true during the precolonial period when armed combat was much more frequent. All indications are that the stereotypes relating to the masculinity of other tribes date from that period.2

The extent to which this scheme reflects reality remains to be investigated. Is it true, as it appears and as the Kipsigis content, that the Maasai are very aggressive, and the Luo very pacific, toward neighbors? And if so, is it because, as the Kipsigis claim, the Maasai are initiated and the Luo not? At the moment we can only speculate whether initiations in other cultural settings have the effects ascribed to them by the Kipsigis.

Even if these stereotypes show some relationship to reality, they are not merely complications of objective observations. The Kipsigis do not approach the subject with blank minds, but with a host of ideas about the nature of proper human behavior, in other words, with a specific cognitive set already in mind, and with a knowledge of their neighbors that is limited in very particular ways.

This approach is narrowly selective in what are considered the significant differences between the Kipsigis and their neighbors. There are many dimensions other than initiation on which these groups differ, but these dimensions do not carry the same weight in patterning Kipsigis ethnocentrism. For example, the strong values against physical and verbal aggression toward any Kipsigis (or even any Nandi) is in strong contrast with the conflicts between different subtribes among the Maasai, or between different territorial units (based on descent) among the Gusii and Luo prior to pacification. In fact, the Kipsigis seem to be almost completely unaware that their neighbors differ on this aspect of social structure.3

Also, the ecological similarities of the Gusii and Kipsigis areas, which are in sharp contrast to the lower, dryer areas inhabited by the Maasai and Luo have widespread implications for behavior patterns (increasingly so as agriculture become more intensive). Yet the Kipsigis make no great distinctions along these lines. And although the Kipsigis recognize differences in the typical physical types of the various groups, they do not attach any behavioral significance to them. In fact, their characterization of the rather slightly built Maasai as extremely tough warriors, and the Luo, who are often very large and well muscled, as insignificant in combat seems at first illogical.

Similarly, most of the anecdotes concerning the Maasai and the Luo refer to intertribal combat in the past and represent (to the extent that such conflict has been eliminated) a time lag in the imagery used to portray these peoples.

It also appears that the evaluation of outgroups according to their relative masculinity (as indicated by their initiation practices) is of some utility to the Kipsigis only within the narrowly circumscribed range of their precolonial contacts with the Nandi, Luo, Gusii, and Maasai. The cognitive framework involving initiation would probably have to be greatly modified, or not used, if the Kipsigis were to find themselves adjacent to the uncircumcised, but bellicose, Turkana or Karamojong.4

In many ways, then, the characterization of surrounding tribes based on ideas of initiation and manhood represents not just a simplification of the social reality but an imposition of pre-conceived ideas and interests on that reality. But why do the Kipsigis attach such importance to initiation, and why do they find it necessary to comment on its presence or absence among other tribes?

The data suggest that the motivation behind such ethnocentric applications of Kipsigis categories to outsiders is not just a desire for logical conceptual consistence, but also involves a degree of displacement of psychological tensions arising from a concern with one's own masculinity.

Clearly the Kipsigis do not consider these other groups with the detached `intellectual' eye other peoples are reported to use when classifying their natural environments (Levi-Strauss 1966). Maasai and Luo are not trees; they are people and are, in some sense, obviously directly comparable to oneself. In what ways, then, do the distinctions which Kipsigis make among outsiders reflect differentiations which are considered critical within the Kipsigis context?

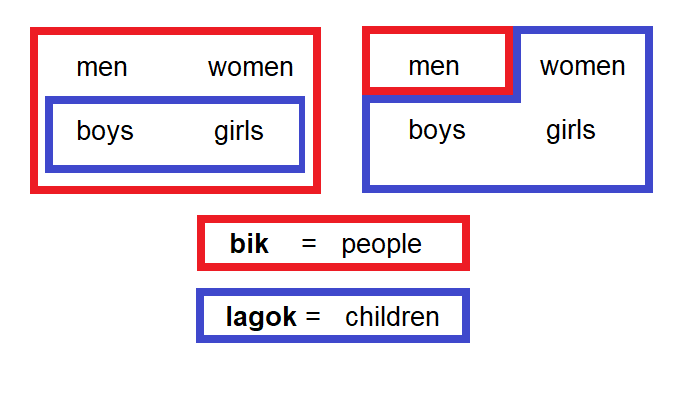

One meaning of circumcision, or its absence, in Kipsigis society is that uncircumcised males are associated with females. For Kipsigis men the major division between social categories is that between men and everyone else. This is clearly seen in the use of the plural forms of the terms for the various age-sex statuses. In most discussions the terms murenik (young men) and kwonyik (women) are used to mean men and women generally.5 Lagok literally means children, and refers most directly to boys (ng'etik) and girls (tibik).6 However, lagok is used in most everyday contexts to mean women and children. Thus the greeting Chamege lagok? (Are your children well?) refers to a man's wife and children, i.e., his dependents.7 When addressing his wife, a Kipsigis men often address their wives as "children!", "logochu!" (the vocative form of lagok).

In contrast to lagok are bik (singular = chito), which means most generally "people" as in bik ap Kipsigis, the Kipsigis people. If asked specifically, everyone agrees that women and children are bik, but this is not the everyday use of the term. There are expressions, such as kotunji toloch (discussed in Chapter 2) in which the particle -ji (-chi, a person, someone) explcitly means a woman. In situations in which lagok is used to mean women and children, bik refers to men. Thus a visitor inquires of a woman at home alone Ngoro bik?, Where are the people?, meaning "where is your husband?" Similarly, if one asks how many bik there are in the community, the answer is the number of independent male household heads; the others are lagok. And thus when a Kipsigis says of his initiation "I stopped being a child and became an adult" he uses words that imply that he ceased being associated with women and girls and joined the men. These usages can be diagrammed as follows:

The Terms Bik and Lagok

The literal Meaning vs. General Usage

These semantic distinctions fit closely with many behavioral distinctions made between men and women: in the spatial arrangement of people in and around houses; in the separations made in eating in terms of time, place, utensils, and in some situations foodstuffs; in the differences in the types of work done around the house: in the distinction between those who can and those who cannot offer opinions at community meetings; and in much more. In each case children of both sexes are grouped with the women and children, lagok, differ from men in certain personality traits that are common to both women and children. For example, they are said to show much less judgment and responsibility in their tasks if unsupervised. In innumerable ways Kipsigis boys are separated from the men and associated with the females.

Thus an uncircumcised Luo man, not being fully a man, is something less; he falls into the category of lagok, women and children, and at this level the distinctions between women and children are not important for they are similar in so many ways that set them off from men.8

But beyond this rather direct extension of Kipsigis categories to outsiders, I think it is clear that for a Kipsigis man the existence of a Luo man poses some problems that have direct implications for his own self image. A Luo man, in the flesh, causes cognitive dissonance – he just does not fit the categories. Obviously he is not a woman or a boy, but a man, a warrior (at least in the recent past), an owner of cattle, a husband, and a father. Obviously Luo men were elders and war leaders in their own communities. But if he is a man without the benefit of an initiation, what was one initiation all above? If one wasn't being changed into a man during those months (or weeks) in the bush, if one did not have to endure the pain of the operation and the beatings and the other hardships to become a man, then the elders and their understanding of life were wrong. The way out of this contradiction, and I contend it is the way most Kipsigis take, is to say that a Luo may appear to be a man, and may think that he is behaving like a man, but that in fact he is wrong because he does not have the proper understanding of manhood. Without the ordeals of initiation, the Luo must lack the proper aggressive spirit of warriors. Without the self-assurance of men, they must be frightened of witches and are fearful at night like little children. According to Kipsigis "knowledge", Luo men play with their small children, rather than remaining properly aloof and the explanation must be that they lack and appreciation for the prestige of manhood.9 What can be better proof that they don't know the first thing about how to behave than the fact that they marry (uncircumcised) children and have children by them.10

I argue that it is not just a desire for intellectual neatness, but a need to bolster one's own self image that leads Kipsigis men to make comments of this type about the Luo.

The persistence of these stereotypes (in terms of both their structure and the sentiments associated with them) may thus be one of the results of Kipsigis male initiations.

The congruence between the ways in which a Kipsigis man thinks about himself and the ways in which he thinks about a non-Kipsigis comes about by an extension of the former to the latter. Even the child learns about outgroups to some extent, but it is only in adult life that most Kipsigis have contact with members of other tribes (surely this was even more true of the precolonial situation), It is postulated here that the categories one applies to oneself and one's group are the primary or central ones, and that it is these ideas as they relate directly to being Kipsigis that are the main message of initiation for the initiates. Ideas about non-Kipsigis are included in the rituals only where they fit the pre-existing patterns of thought. The Kipsigis do not feel that they should practice circumcision because the Maasai do or because the Luo do not. They feel that it is basic to being Kipsigis per se.11 I do not think that the relationship between the initiations and the patterning stereotypes is simply the result of a communication of categories as such. Rather, the initiations deal more directly with conceptions of the self relevant to the ambiguities that develop out of typical childhood experiences, and the personal cognitive commitments resulting from this pattern of childhood experiences as reworked by initiation experiences contribute to the continued psychological investment in these stereotypes among men of the next generation.

If we assume that initiations have some effect on the development of sex-role identity, we must also assume that this effect is limited, that there is some continuity between individual personality patterns before and after initiation.

As mentioned briefly in Chapter III, newly initiated young men appear to be more serious than their former selves, acting in public with an aloofness and arrogance they did not display as boys. Peristiany, who observe initiates who had been secluded for some months, commented that "even a casual observer notices ... that the boys take at least six months to recover" (1939:26). If we also consider some of the stated aims of initiation, and the statements of at least some of the Kipsigis that they were changed by initiation, it seems reasonable to assume that this may be empirically demonstrated.

The second assumption being made here is that the effects of initiation will be in some form a re-ordering or recombination of old and new elements, some changes in emphasis in the various tendencies of the individual personality, some awakening or fuller development of patterns already latent, in at least some rudimentary form, in the individual personality prior to initiation. The opposite assumption would be that there is no continuity between the personality before and after initiation; that after initiation the identity of the initiate is not only qualitatively different but is unrelated to his childhood experiences. This assumption contradicts every set of psychological data, and the theories drawn from them, with which I am familiar. Moreover, and most importantly, it contradicts the Kipsigis view of the situation, for despite the obvious behavioral changes, the new status, the new name, and the rest that mark the initiate off from his childhood self, he is still recognized as the same person. He is still the same child (firstborn, lastborn, or whatever) of the same parents. And despite the stress placed on the transformation of the initiate's personality, he is still recognized as being what he is, in part, because of the nature of his childhood. As one would expect, the Kipsigis justify their childrearing practices, in part, in terms of the perceived effects for later life, on occasion referring to a person's childhood to explain his present behavior (for example, one old man who was troubled by the constant disobedience of one of his grown sons explained that it was because the boy's mother had died just after his birth, and from the beginning he was `spoiled' by being fed curdled cow's milk, mursik, and had never known hunger as other children do).

There are even some indications that Kipsigis recognize the influence of fathers on their sons' subsequent adult personalities (though there are proverbs to the effect that sons rarely fulfill their fathers' expectations). One man related to me that he was once told by a total stranger that it was obvious from his behavior that his father was a man of particularly strong character (which was true). The same informant also said that he had frequently observed that men who had been raised without fathers found it much easier than himself to ignore the social distance between men and women, and to chat and gossip with women in a way that he always found difficult.

Thus some understanding of the effects of Kipsigis initiation (and perhaps ultimately of the content of Kipsigis ethnocentrism) may be found by looking at pre-initiation (childhood) experiences. Previous research in a variety of cultures suggests that the interaction patterns of the male child with other people, particularly his parents, may have a determining influence in the development of his own sex identity.

The structure of Kipsigis ethnocentrism is directly related to the conception of manhood and masculinity basic to Kipsigis initiations. It is suggested that the concern with the masculinity of other tribes is related to an unstated concern with one's own masculinity. While this self-concern may be activated by the challenges of the intertribal situation, it appears that its roots lie in more basic experiences within the Kipsigis context. Nor does it seem likely that this concern derives from initiation experiences. Rather, it seems quite clear that initiation is supposed to develop a more masculine identity in the initiate, or as the Kipsigis say, to teach him to be a man. The Kipsigis feel that it is necessary to give the boy in initiation new definitions of manhood, and to reinforce these by both reassurance and tests (which the initiate is to consider as self-demonstrations of his manhood). It thus seems reasonable to postulate that a significant number of Kipsigis boys, prior to initiation, might not have sufficient identity strength as males (as this is defined in the culture) to assume the demands of their approaching adult lives, particularly in the days of the warrior age-grades. Such, at least, seems to be the implication of Kipsigis comments about initiation.

This observation is by no means novel. Research directly relevant to the present study has been carried out by John Whiting and several of his associates, and this study is based in large measure on their previous work.12 Whiting, Kluckhohn, and Anthony (1958) found significant associations cross-culturally between the presence of male initiations at adolescence and the presence (either singly or together) of exclusive mother-child sleeping arrangements during the child's first year, and prohibitions against a mother with a child a year or less in age engaging in sexual intercourse (the post-partum sex taboo).13 The primary interpretation presented in this article postulated the development of Oedipal conflicts in the male child and suggested that these rites are designed to prevent overt hostility toward the father, and other men, at adolescence (1958:361). Later the interpretation was changed (Burton and Whiting 1961; Whiting 1962). It was postulated that in societies with these customs affecting the mother-child relationship, male children would tend to identify at first with their mothers, and that conflicts would arise between this and subsequent identification as males. Male initiation rites were then interpreted as functioning to resolve these conflicts in sex-identity at adolescence, the period of adult identity formation. A person's identity is defined as his position or positions in the system of roles and statuses of his society (1961:87). In any given society there are numerous behavior patterns that are considered sex-specific, and thus many different ways in which an individual can identify with a pattern usually associated with the other sex. Identification with a pattern inappropriate to one's physiological sex is termed cross-sex identification. Burton and Whiting distinguish three kinds of identity; attributes, subjective, and optative:

Attributed identity consists of the statuses assigned to a person by other members of his society. Subjective identity consists of the statuses a person sees himself as occupying. And finally, optative identity consists of those statuses a person wishes he could occupy but from which he is disbarred (1961:87, italics in original).

Discrepancies, particularly on the optative level, between an individual's primary identity formed in infancy and secondary identities formed in later childhood are hypothesized to cause psychological conflict, frequently termed cross-sex anxiety.

Most of the studies that have used this theoretical construct are concerned with situations involving a feminine primary identification by male children.14 High rates of polygynous marriages. exclusive mother-child sleeping patterns, long post-partum sex taboos, and other customs that describe aspects of the child's natal family are held to be indicators of the low "salience" of a male figure for the child during primary identity formation.15 Burton and Whiting have suggested that the crucial determinant of which parent the child identifies with is his perception of which one controls the resources he values (1961:85). They term this the status-envy hypothesis.

All the particular aspects of this hypothesis have not yet been put to thorough testing. Much more research is necessary before we feel confident about the specific ways in which each of the parents influence the formation of sex-associated aspects of the child's identity. Kohlberg deals with these problems at great length in his discussion of the research done in western (primarily American) samples. As he notes, the topic of parental influence on children's sex-typing has led to mixed findings, and the relevant studies have tended to overstate the results:

In almost any of the prevalent theories of parent-identification, the presence of the same-sex parent should be a necessary condition for the development of normal sex-role attitudes or identification . . . In fact, the studies suggest that the father's absence retards development of masculine sex-typing rather than crating gross abnormalities or permanent deficiencies in the formation of a masculine identity (1966:157-58).16

Granted this caution, it can be noted that several studies cited in the reviews of the relationship between family patterns and sex-typed behavior (Burton and Whiting 1961: Romney 1965; D'Andrade 1966a) have demonstrated that the absence of the father from the household during a child's early years has significant effects on the development of the child's personality.17 These findings, and more particularly those of studies (mentioned below) that follow directly from Whiting's initial work on cross-sex identification, suggest that a similar approach may be useful, both analytically and methodologically, for dealing with the relationship between Kipsigis initiation and ethnocentrism on the level of individual personality problems.

The present study is not designed to be a test of the various details involved in a particular hypothesis of the process of sex-identity formation. Rather, it attempts to use the general concept of cross-sex identity, which has received some validation in other contexts, to further our understanding of Kipsigis ethnocentrism.

The analytical approach being used here deals with a model of individual personality development, and postulates a relationship between the conceptualizations of self and others on a level of individual thought patterns. In order to test these ideas in detail, data must be collected for which the individual Kipsigis man is the unit of analysis.

The earlier studies of sex identity in non-western settings used the cross-cultural method. The results generally confirmed the hypotheses based on the theory of sex identity, and in some cases have led to significant modifications of the theory. The cross-cultural methods, however poses some major problems for studies involving psychological dynamics. In such studies the assumption is made that "a custom may be thought to refer to the behavior of a typical individual in a given society" (Whiting 1954:526). This tactic has been used widely in cross-cultural studies dealing with psychological hypotheses, by no means just those involving sex identity (see, for example, Whiting and Child 1953; Spiro and D'Andrade 1958; Shirley and Romney 1962). It has not, however, escaped criticism from those who feel that the relationships demonstrated between the distributions of various customs, for example exclusive mother-child sleeping arrangements and male initiations, can be more directly explained on the societal level in terms of group dynamics (Young 1962; 1965). Aside from the many misunderstandings that have clouded this debate, the differences between these views are actually quite subtle, including the fact that different questions are being asked, and involve some deeper philosophical issues about the causality of human behavior patterns. Briefly, it is Whiting's position that there are certain psychological needs that arise from early life experiences and that if a particular set of needs typifies a sufficient number of people in a given society "there will be institutions developed by the society to help its members resolve" these needs one way or another (Whiting 1962:394). Young favors a "symbolic interaction explanation" (1962:381) based ultimately on Durkheim, and attempts to explain the presence or absence of male initiations in terms of differing organizational needs arising out of more basic variations in the structuring of adult sex roles in societies. Whiting is concerned with the psychological integration of a typical individual's behavior patterns as mediated by continuities in personality through various stages of life; Young with the societal-level integration of interpersonal interaction patterns in terms of the functional requirements of groups.18 As such it is doubtful that these differences can be resolved on the basis of empirical results.19 Nor is it within the scope of this study to attempt a theoretical integration of these two positions. We can note, however, that theories developed using cross-cultural methods but based on the individual as the unit of theoretical reasoning, can be further tested on samples of individuals from particular societies, with the individual as the unit of data analysis. If the relationship, say between low father salience and cross-sex anxiety, which appears to hold true in the cross-cultural studies, is a useful analysis of individual psychological processes, the same relationship should be found on the individual level. The demonstration of general principles using this sort of shift in the level of analysis has been called sub-system replication.

Such a step often necessitates a modification in the measures used. In cross-cultural studies it is desirable to focus on variables which have the same value for all relevant members of the society, since one wants to minimize the effects of individual variation. A variable such as male initiation, which is (in most cases) either totally absent or universally practiced in a given society, is well suited for studies of this type. In replication studies involving a sample of individuals drawn from one society, it is precisely individual variation that is of interest, while every attempt is made to minimize cultural (for example caste or regional) variations. The shift from considering a certain difference between a typical Trobriander and a typical Tiv to an analogous difference between two Kipsigis of the same community requires more sensitive measures, or at least more subtle interpretations of the same diagnostic traits on which the measures are constructed. Since all Kipsigis men are initiated, the useful distinction for constructing a measure of the effect of initiation on subsequent behavior becomes the degree of severity of their individual initiation experiences.

A number of Whiting's associates have now conducted studies dealing with the theory of sex identity using culturally homogeneous samples of individuals, though these studies have not yet been published. Some of them are:

-

`

- "Efffect of early father absence on scholastic aptitude" (Kuckenberg 1963) based on a sample of American college students.

- "Parental absence and cross-sex identification" (D'Andrade 1966b) based on a sample of 121 children and fifty mothers from Black American and Barbadian working class families near Boston.

- "Male pregnancy symptoms and cross-sex identity (R. H. Munroe et al. 1966) based on a sample of 56 lower middle class white males from the Boston area

- "A study of couvade practices of the Black Carib' (R. L. and R. H. Munroe 1966) based on a sample of 49 Black Carib men in British Honduras

The patterning of Kipsigis stereotypes, and the suggested motivation for Kipsigis evaluations of other groups, is also conceived here in terms of individual thought processes. But stated in these general terms, the discussion contains two problems. First, if the analysis is made on the level of Kipsigis culture as a unit, then there is only one test case of the ideas involved; there is no way to know if the negative and positive evaluations of the other tribes are, in fact, related to sex identity empirically - the description is inseparable from the analysis, and evaluation of that analysis remains subjective. Secondly, a single unit analysis of this type disregards the variation in individual opinions about the Maasai, the Luo, and the others, which was one of the most interesting aspects of the field situation empirically, and the best chance, analytically, to test the ideas presented here.

The collection of data from a sample of individuals allows the following strategy:

- It is argued that the application of Kipsigis concepts of masculinity to other tribes is related to a concern on the part of the typical Kipsigis male with his own sex identity, and that this ambiguity results from certain childhood experiences as modified by initiation.

- If this is so, then the extent to which the conditions hypothesized to lead to cross-sex anxiety were present in a particular individual's early life should predict both to the degree of relative masculinity of his present self identity and the degree to which his individual evaluations of the neighboring tribes resemble the general stereotypes.

The specific hypotheses can now be stated in detail:

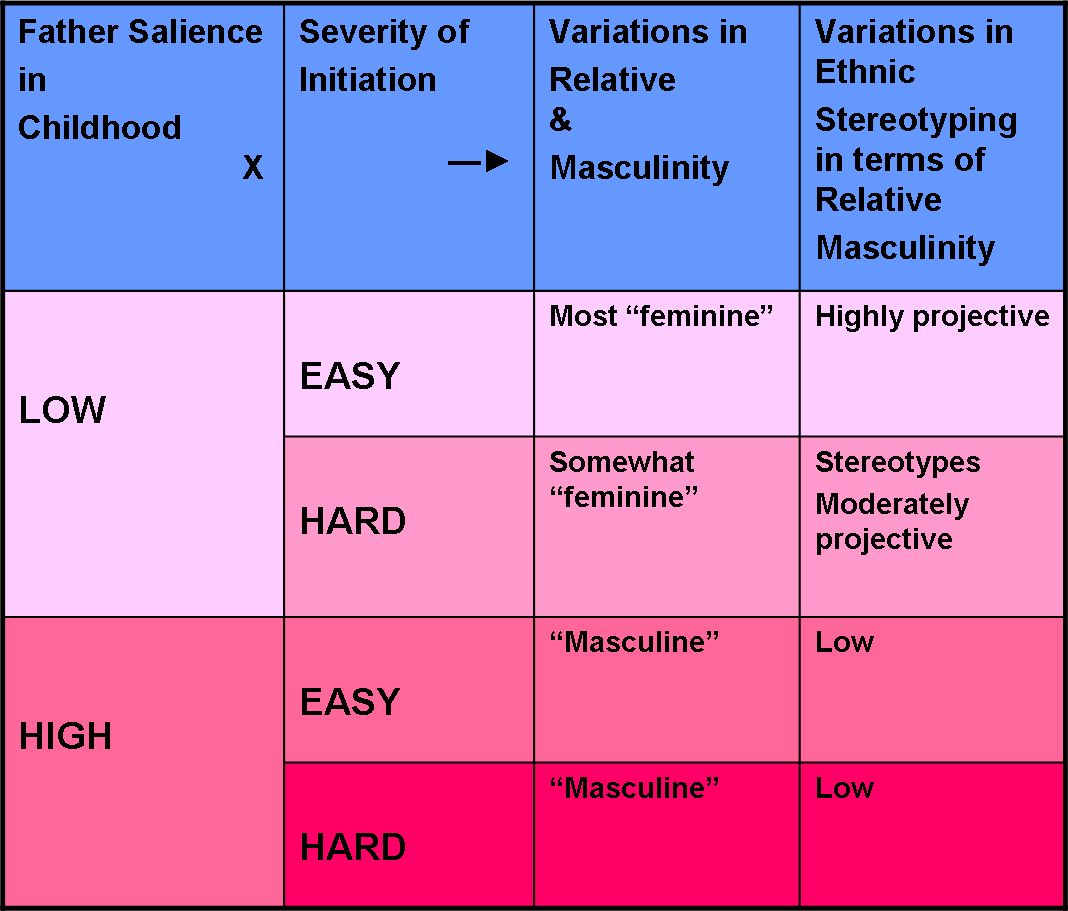

- Those men whose childhoods were characterized by low father salience will score relatively more feminine on measures of sex identity.

- Effect of Initiation

- To the extent that this pattern is modified by initiation, those men who experience more severe initiations will score relatively more masculine.

- Since it is hypothesized that initiations function to resolve cross-sex anxiety by reformulating the initiate's identity on a clearly masculine basis, it follows that the severity of initiation will make a greater difference for those who presumably entered adolescence with greater cross-sex anxiety. Specifically, the effect of initiation severity will be stronger for men with low father salience during childhood; variations in initiation experience will have little or no effect on the men with father salient childhoods.

By "severity of initiation" is meant the level of actual physical hardship caused the initiand (torusiot) as measured by some relatively objective criteria, and not the subject's reported perception of the severity of his initiation.21

- The general pattern of responses, for distinctions relating to relative masculinity, will be: Maasai considered as very masculine, Luo as very feminine, and Gusii and Kikuyu as intermediate, Kipsigis (Nandi) will also be considered highly masculine.

- Degree of commitment to ethnocentric stereotypes:

- Those men whose identities are relatively less masculine will make greater distinctions between these tribes along this dimension of relative masculinity than along other dimension, and in this respect will differ from the other respondents.

- Those men whose identities are relatively less masculine will also tend to identify the Kipsigis more closely with the Maasai (and farther from the Luo) than will the other respondents.

1 Due to the teachings of Christian missionaries there are now some men, very few in number, who have been circumcised, but who have not undergone the traditional rituals. Attitudes toward these "hospital initiates" are discussed in Part II.

2 Attitudes toward the Kikuyu, with whom the Kipsigis had little contact until the colonial period, are discussed in Part II, as is the question of whether the strength of the stereotypes relating to relative masculinity vary for different age groups among the respondents.

3 A Kipsigis man who was in charge of organizing sports teams and other social activities among a group of Gusii workers on a tea estate near Kericho complained that it was nearly impossible to get them to cooperate among themselves. Although he was well educated and widely travelled, he could not understand their fractiousness. The fact that the men were from different areas in Gusii (different clans) did not give him any clue to their behavior.

4 The few Kipsigis I met who have had contact with the Turkana (while serving in the security forces) tend to think of them as "naturally" aggressive and dangerous ("like wild animals"), The extension of Kipsigis concepts of masculinity to the Turkana would lead to some extremely unrealistic expectations about their behavior.

5 For polite forms of address the terms boisiek (elders) and chebiosok (old women) are used. These terms are used by the Kipsigis as translations of "Ladies and Gentlemen" when starting a public address and are used to convey respect in a variety of situations.

6 The distinction between boys (ng'etik) and girls (tibik) is not generally made when referring to small children, those too young to do chores responsibly (less than age five approximately), who are usually referred to simply as lagok. It is also more polite for adults to address a boy as lakwani ("child") rather than ng'eta ("boy") as the latter term is related etymologically to the command "get up" ( ... and go and do such and such) and thus emphasizes his subservient status.

7 Here, as in many other forms of greetings, the plural is used even if only one person is being referred to (it is considered gracious to address a girl as tibik, "girls," etymologically "those who attract people"). It is also a form of politeness to inquire about a man's children even if he is unmarried but of the appropriate age (this was true both in my case and that of some Kipsigis men I knew).

8 The logical conclusion here is that Kipsigis men attach much less significance to female initiations than to their own. Much of their behavior at female rituals suggest this is so.

9 My information on this comes only from Kipsigis informants. If it is true, it would appear directly relevant to the theory linking weak father-son relationships to the presence of initiations which has been used in cross-cultural studies.

10 Until the many social changes of the last few decades, all females were reported married within a few days of their emergence from initiation seclusion. And all children of a married woman were legally children of her husband (though it is distasteful if they are the result of an adulterous union). Truly illegitimate children, by Kipsigis definitions, were those born of uncircumcised mothers. In the past these children were usually put to death at birth, if it was not possible to rush the pregnant "girl" through initiation before the birth. Although these practices have changed greatly (most girls are not married immediately after initiation, and pregnancies in such cases are a new and very troublesome problem), they are another instance of Kipsigis customs which, if applied to evaluating Luo behavior, place the Luo in a bad light.

11 The historical origins of initiation among the proto-Kalenjin peoples, if it will ever be possible to determine them, may indicate that circumcision was borrowed from some other group (usually postulated to have been a Cushitic group). But such questions lie beyond the scope of this study. For the present Kipsigis it is unnatural not to practice both male and female initiation, and the only explanation they offer for its absence among some other groups is that they must have been isolated from everyone else and forgotten how to perform the operations and rituals.

12 The above interpretation of the connections between the nature of Kipsigis male initiations and the quality of their stereotypes of neighboring tribes came only after reflections on the first series of initiation ceremonies to be held during the period of fieldwork in December, 1965. During the latter part of 1965 and early 1966, I had become increasingly aware of the "sexual" aspects of Kipsigis stereotypes when I was involved in interviewing an old man about precolonial conditions and studying Kipsigis culture in general. Early in 1966 I decided to focus my attention on one community (kokwet). The opportunity arose shortly after this decision to collect extensive data on this community while working with the Child Development Research Unit (an organization designed to collect data on, and establish continuing contact with, sample communities in several tribes in Kenya in order to facilitate cross-cultural studies). I had long been interested in Whiting's hypothesis concerning male initiations and was aware, rather vaguely, that it related to the patterns I perceived in Kipsigis ethnocentrism. It was not, however, until some time in the fall of 1966, after several lengthy discussions in Kenya with Robert L. and Ruth Munroe (the field directors of CDRU at the time) that I fully grasped the utility of the work on cross-sex anxiety in structuring my ideas on initiations and stereotypes into testable hypotheses. The preliminary research design also benefited from many useful suggestions made by John and Beatrice Whiting. I am also indebted to both the Whitings and the Munroes for many of the specific measures used in these interviews.

13 As defined operationally by Whiting et al., and as is the case among the Kipsigis, the post-partum sex taboo does not apply to sexual intercourse between the father and another partner.

14 The question of sex identity conflicts for females, and their relationship to female adolescent rites is the subject of a cross-cultural study by Judith K. Brown (1963).

15 In a further article (1964) Whiting has attempted to explain the geographic distribution of male initiation rites in terms of climatic conditions and the effects these have, indirectly through economic adaptations, on child-rearing practices.

16 It should be stressed here that this study is concerned with relatively slight personality difference among Kipsigis men, and that expressions such as "a relatively feminine identity" or "anxiety concerning one's own sex identity" are not meant to imply the presence of behavior patterns beyond the acceptable range of male behavior among the Kipsigis. This study is not concerned with homosexuality and does not assume that homosexuality is related to the variables discussed here in any direct way, if at all. It should be noted that overt male homosexuality is, as far as can be determined, extremely rare among the Kipsigis.

17 Perhaps of most direct interest to Kipsigis masculinity as it relates to neighboring tribes are the studies by Sears (1951) and Stolz et al. (1954). For a sample of American children, Sears found that boys from father absent homes showed less aggression in doll play than boys from father present homes at ages three and four. There was no significant difference, however, among the five year old boys (father absence did not affect the level of aggression in doll play among girls, which was on the whole less than that among boys). Stolz found that boys who had been separated from their fathers in infancy but since reunited were more feminine in overt behavior but also more aggressive in play situations (fantasy behavior) than boys whose fathers had been present throughout their early childhoods (both studies cited in Burton and Whiting [1961] and Romney [1965]).

18 This same controversy has also been raised concerning the cross-cultural study of menstrual taboos. See Stephens (1961) and Young and Bacdayan (1965).

19 Trying to test Whiting's or Young's basic hypothesis of the functional causes of male initiation rites on the basis of the Kipsigis case by itself can lead to a sterile chicken-or-egg problem. Neither Kipsigis adolescents not the initiated members of age-sets reinvent the idea of circumcision and the associated rituals each year. Initiation is as much a part of the cultural heritage of an individual Kipsigis male as are the exclusive mother-child sleeping patterns and the exclusive male social categories mentioned above. One can, however, ask why some Kipsigis adolescents feel very strongly that they must undergo initiation these rituals, and why some men feel strongly enough about them to take an active part in performing them year after year. In this sense, one might speak of a "need to be initiated" or a "need to perform initiations." Given the existence of initiations among the Kipsigis, the question is what sustains them.

20 See footnote 1.

21 Following the basic hypotheses, it was expected that the subjective perception of initiation severity would be liable to great distortion, especially among the father-absent respondents who, it was anticipated, would tend to minimize the level of discomfort actually experienced.