MALE INITIATIONS

The following is a description of how one boy, who was then in school and living with his family on a European farm north of Kericho town, arranged to enter an initiation group:

If feasible, four to six boys from one primary community, a kokwet, are grouped together. Usually there are not enough candidates within the kokwet to form a seclusion group and so boys from neighboring communities are put together. It is not considered significant if some of the boys are unacquainted with each other.

The other offices, of course, require men with an active interest in the content of the rituals, and a senior position in the area. Although many men eventually serve as kwanda, feeding initiands, few men become moteriot or boiyot ap tumdo. If for some reason the fathers of the candidates cannot find men in their local area who have served in these roles in the past, they may look for officials from a few miles away, or ask a local elder who has shown keen interest in the rituals to take a role. They will first decide among themselves who will he kwanda. While most men presumably want to see that their sons are well cared for, and the role of kwanda is profitable (for the other fathers will pay the man who feeds their child one head of cattle or an equivalent amount of cash), the man undertaking the responsibility must have a great deal of food to spare as well as the time required of both himself and his wife. The date of the initiation depends upon the other commitments of the operator, and possibly the senior moteriot. Operators frequently schedule three groups on the some day, and moterinik occasionally do. In some cases it is not possible to get a full set of officials for the weekend following the closing of school. In such cases the initiations are held the next weekend.

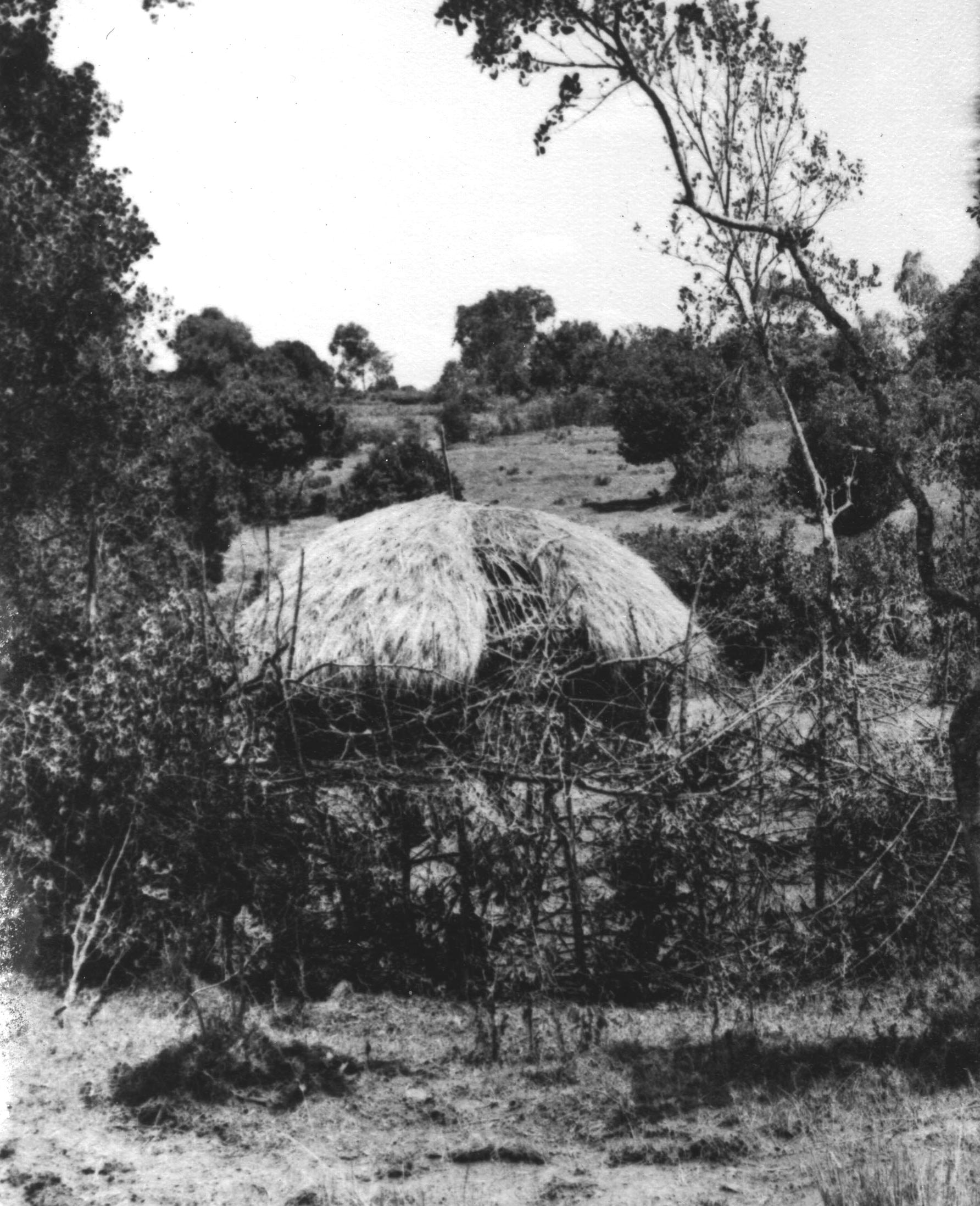

A Menjo in the Bush

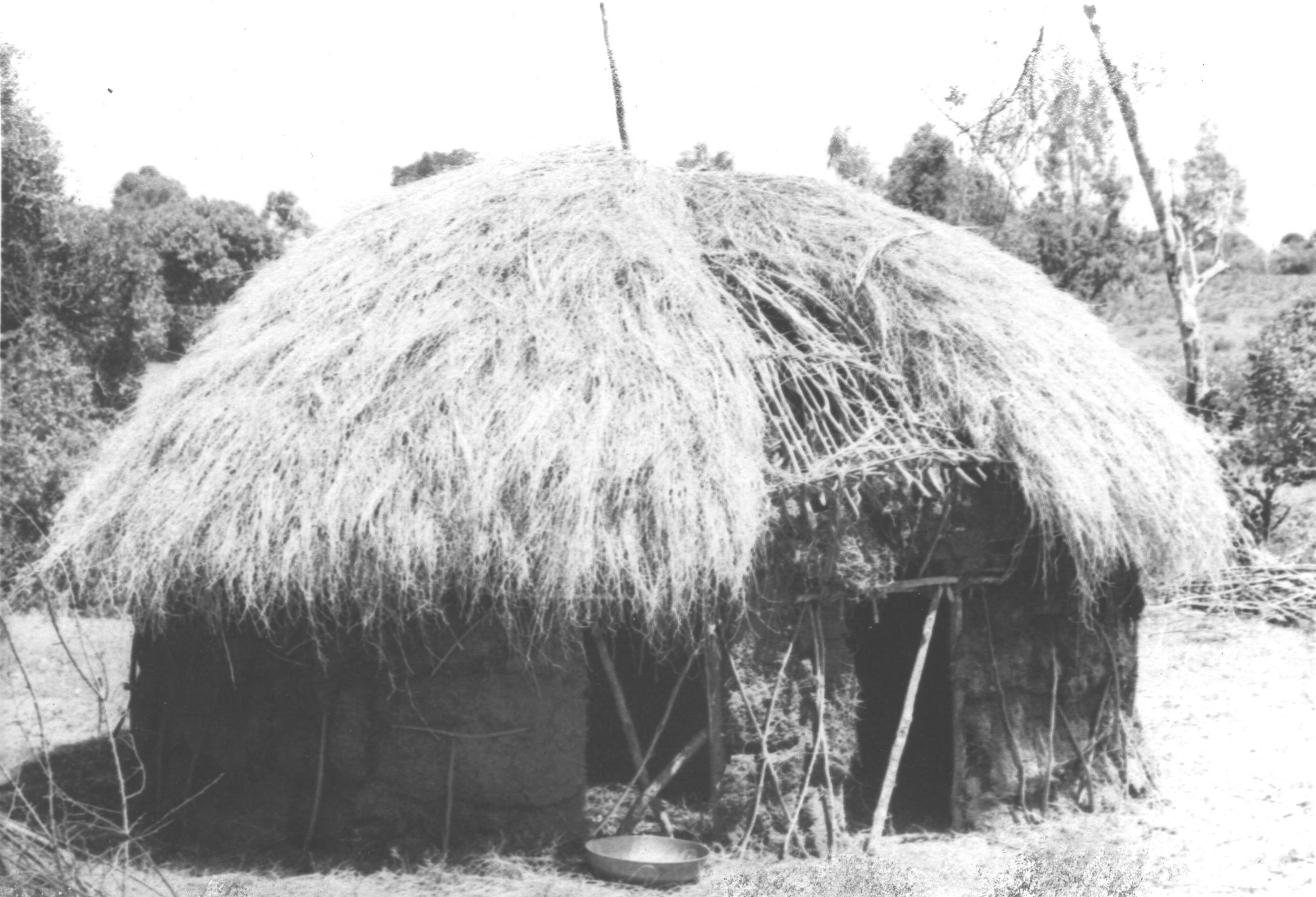

It is said that the candidates for initiation build the menjo, but today at least the major amount of work is done by their fathers, assisted by other men, mostly young men, from the local community. The menjo hut is built along the lines of precolonial houses, i.e., rather than using introduced species of trees for posts and long beams to form a conical roof, smaller supple trees and branches are used, and the frame of the heuse is, in effect, a very large inverted basket with a curved, domed roof. Unlike ordinary houses a floor is not prepared, but the natural grass is left inside the menjo.

The construction of the menjo starts with a circle, twelve to fifteen feet in diameter, of thin posts about four feet high. The posts are lashed tegether with three horizuntal double rings of long green branches, Other branches are then placed vertically down between these three double rings, secured,and bent over to meet in the center, forming the apex of the roof. Two circles of vines, about eighteen inches in diameter, are used to secure the ends of the roof pieces to a short center post, creating a dome supported by the outside wall. The roof is filled in with as many branches as possible, and these are secured with twisted vines woven around the root at regular intervals.

Candidates and Their Fathers Building a Menjo

Almost all of the construction of the frame is now done by the men, particularly the fathers of the candidates. The boys assist in collecting materials, and fetch the next piece as it is needed. In one case, where a simple fence was also built, this was done mostly by the boys. No women or girls are allowed near the menjo from the start of its construction (except at the moment of the first operation, described below).

The building of the frame is done over several days, a few hours at a time. when it is completed, two small doors are left (actually gaps in the framework) about two feet wide and three and a half or four feet high, about a yard apart. Screens are made for these doors by pressing grass between a double lattice of branches. These “doors” are not attached to the house, but are placed aside against the outside wall during the day. This was apparently the original method or closing entrances before the introduction of fitted, hinged wooden doors now used universally on regular houses. The frame is then thatched roughly.

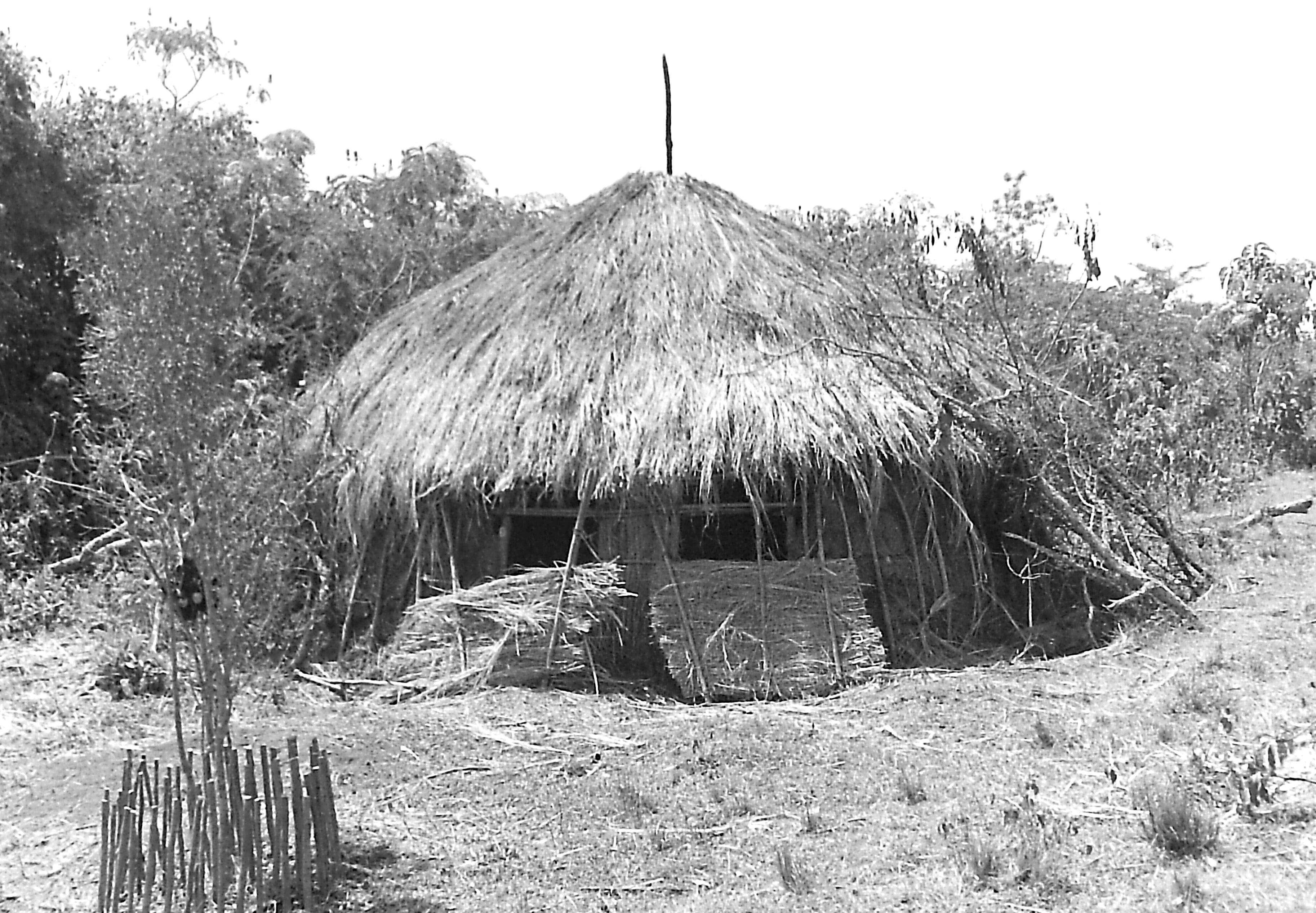

A Menjo Awaiting Completion by the Moteriot

The senior moteriot must complete the thatching of the wedge of roof just over the doors. If necessary, this will be left for him to do after the rest stands completed. The walls are filled in by the boys with large chunks ofearth. It is roughly packed and is not smoothed or given a plastering of mud and dung as regular houses are (plastering of houses is done by women and girls). The thatch is not trimmed along the eaves, and the menjo thus looks extremely crude compared to women’s houses. Some Kipsigis find this rough quality of the menjo amusing, and consider the unplastered walls a sign of the boys'lack of knowledge. The framework, however, shows a great deal of skill, and it is obvious that the appearance of a menjo is not simply due to the boys‘ limited abilities at house building.

A Completed Menjo

With a Mabwaita (left foreground)

For the last several days before initiation the candidates gather in the evenings at each other's homes to practice the initiation songs to be sung the night before the operation. During this period they are accompanied by uninitiated girlfriends of their age. Same informants reported that they are allowed to sleep together "as adults do" (rather than being restricted to interfemural intercourse and other forms of sex play).2

When the boys come home, they are fed and given some fermented porridge (musarek) to drink. Later in the day they take the long branches of korosek and tie them together with the sinendoik creepers into fronds which are then placed in the mabwaita, a cluster of sacred branches tied to a stake a few yards from the door of their mother's house (Kipsigis speaking English usually translate mabwaita as altar ).

During the day the guests arrive bringing gifts to the boy's family. By late afternoon the beer party at the candidate's house is well underway. The candidate stays outside with the other children and those women who are cooking and serving food. Late in the afternoon he is called to another house on the homestead. His mother, or whoever is acting in her place, shaves his head, and gives him her skin cloak (koliget, plural koligoik) to wear. The boy also puts on a bead necklace given to him by his mother, and possibly other ornaments given to him by female relatives or girlfriends. In the cases I observed, the candidates did not put on their skin cloaks early in the evening, but were given new light-colored blankets instead.

A Father's Speech

Following the father, each of the other adult males of the homestead, and some of the other male agnates, anoint the boy and make their speeches. The mother and other female relatives also make brief speeches. In general the women's speeches are more concerned with farewell and impress on the boy that he is leaving them forever as a child. While the mother's speech is not as heated as that of her husband, she also reminds the boy of all she has done for him during his childhood. One mother, on the verge of tears, lamented that she would no longer be called Obot Kibet, Kibet's mom, a teknonym using the name of a woman's young child, but would now be known formally as kamet ap Arap Cheramgoi, the mother of Arap Cheramgoi, that her boy would no longer come skipping into her house asking for food, etc. Now she can no longer help him, he is on his own, and must go through with his decision to be initiated.

Following the speeches, the group moves on to another house, where the candidate may join a fellow who is being anointed. There he stands beside his friend and is also anointed, though he is not the main object of the parents‘ charges of responsibility. From the anointment by their parents until the final bathing just prior to emergence from seclusion, the subjects of initiation are known as torusiek (singular, torusiot}, initiands. The same term is used for males and females.

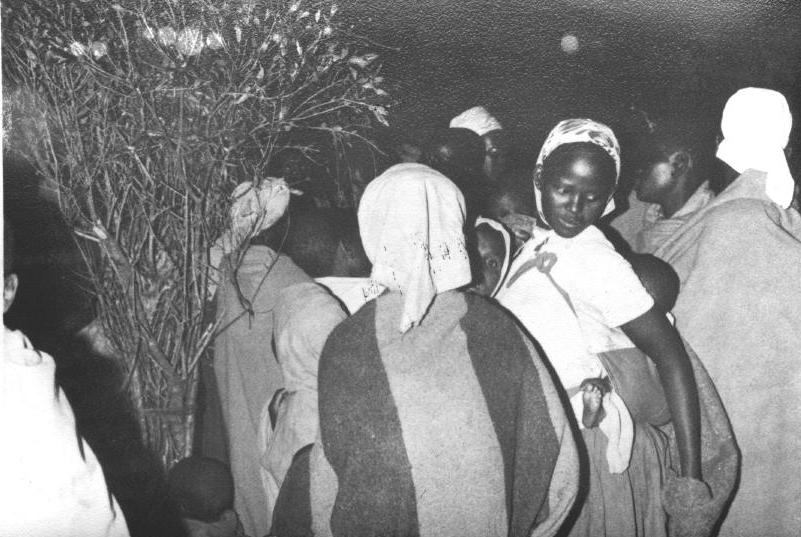

A large fire has been built outside, near the mabwaita. Women and children gather in a line by the fire and call the initiands to come over. Standing just in front of them, they start singing songs addressed to them. Their mothers and other close female members of their homesteads (mother's cowives, sisters-in-law, older sisters) lead most of the singing. The songs consist of a series of brief phrases followed by a general chorus (oleyo - loleyo-ee, no meaning). The words of the verses mock the initiands, telling them that if they are worried, they should go to live with the Luo if they cannot endure circumcision, that they are depending on them and do not want to be shamed, and so forth. The initiands are expected to respond to the songs, and to join in, but most are almost completely silent during the women's singing. The songs are felt to encourage the initiands, to restore their determination and to stop them from worrying.

Women Gathered by the Mabwaita

Outside the Beer Party at the Kwand'ap Ng'etik's Home

Usually shortly after the women start singing, the younger men gather outside the house and start their own song. They stand around in a circle holding an upturned shield, beating the rhythm on it with clubs (the Kipsigis do not use any drums). They pull a candidate into their circle and make him join the swaying of the group. The men's songs are in competition with the women's songs just a few yards away, and each group strives to drown out the other. The men's song, like that of the women, consists of several short verses, sung in turn by various men, followed by a brief chorus. There is no specific order or number to the verses, and any one man does not know all the verses sung on one night. There are verses which celebrate the clan affiliation of the singer, for example the following sung by a young man of Kapkomosik, a clan derived from the Okiek (or "Dorobo”), a Kalenjin-speaking group living in the high forest by hunting and gathering):

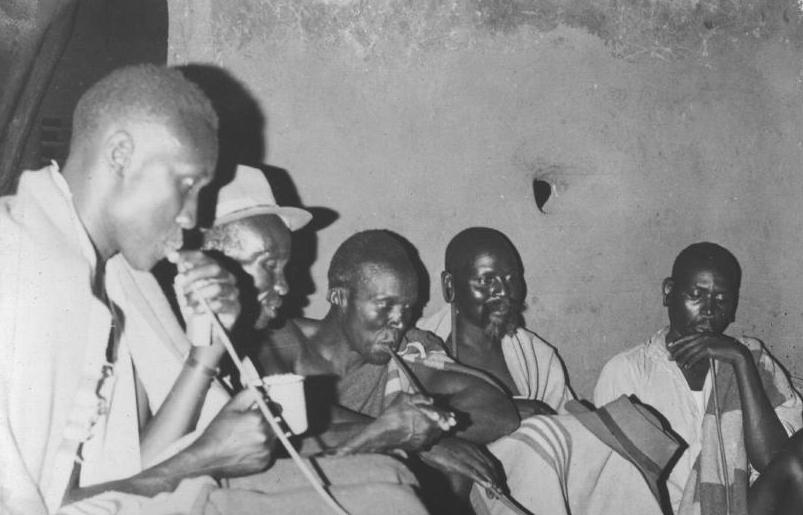

While the tone of the women's songs are very serious, and remind the boy of his obligation to uphold his family's expectations, the singing by the young men is rather raucous at times and is more of a verbal assault on the candidate. Initiands show a reluctance to join the men's singing. While all this is going on outside, the fathers, and the older men are inside drinking beer. While Kipsigis beer parties in general are rather quiet, orderly affairs, with the young men of the homestead directing the serving of beer and the allocation or beer tubes, the party on the night of boys' initiation is particularly solemn, and side conversations are kept to a minimum. There is a very noticeable sense of restraint in the air, even a touch of tension, with the realization that the important moment is yet to come.4

The Beer Party at the Kwand'ap Ng'etik's Home

As all this goes on for a couple hours, and midnight approaches, the moterinik have left the beer party from time to time to direct the younger men in preparing a nearby house, usually the largest house on an adjacent homestead, for the rituals that follow. When everything is ready at the other house, the senior moteriot returns to the kwanda's house, signaling that it is time to end the beer party.

The candidates are then taken a short distance into the bush by the young men to wait while the older men take up their places in the Kot ap Tumdo. The women collect the children and go to their homes with their female guests from other communities, where they will spend the remainder of the night.

By this time, usually between midnight and 1:00 a.m., the initiands have been brought to the Kot ap Tumdo. They are seated outside by the mabwaita where a fire has been started. While the moterinik are making the final preparations inside, the initiands are interrogated by some of the young men. They are made to confess if they have ever had sexual intercourse with any woman, and if so, with which woman, and how many times. They are threatened by the young men that their initiation will go wrong and they may bleed to death if they hide the truth. The questioning persists until the young men are satisfied that the initiands have told them everything.

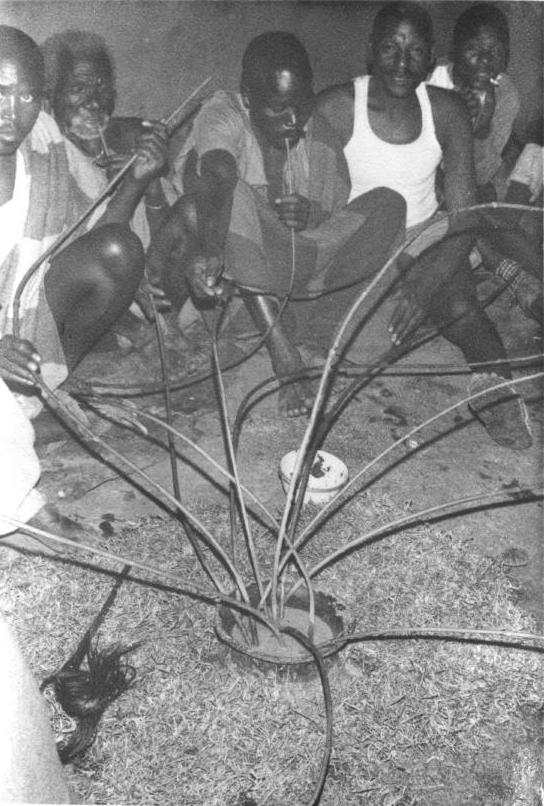

The moterinik then come out and lead the initiands around the mabwaita four times. They then collect the skin cloaks, koligoik, which had been given to the candidates earlier in the day by their mothers. These are taken inside and thrown ever the top of the kimusang’it tunnel. The senior instructor takes his place at the head of the file of initiands, and the junior instructor brings up the rear. All get down on their hands and knees, each with his head pressed against the buttocks of the one in front, and enter the house. As they enter the men fall silent. The file of initiands, with their instructors, crawl through the kimusang’it four times. The nettles sting their backs, arms, legs, and foreheads, causing a burning sensation and slight swelling. As the initiands pass through, the younger men press down on the skins covering the passageway increasing the amount of stinging. Throughout this whole scene the initiands are completely naked. When they have completed four circuits they line up by the door and join in singing the initiation song four times, with the senior moteriot leading them, and four times with the junior moteriot leading. Then the line of initiands and their instructors crawl around the outside of the kimusang’it four times, counterclockwise, and sing four more times. After that the initiands are led outside, still in file, and seated around the fire.

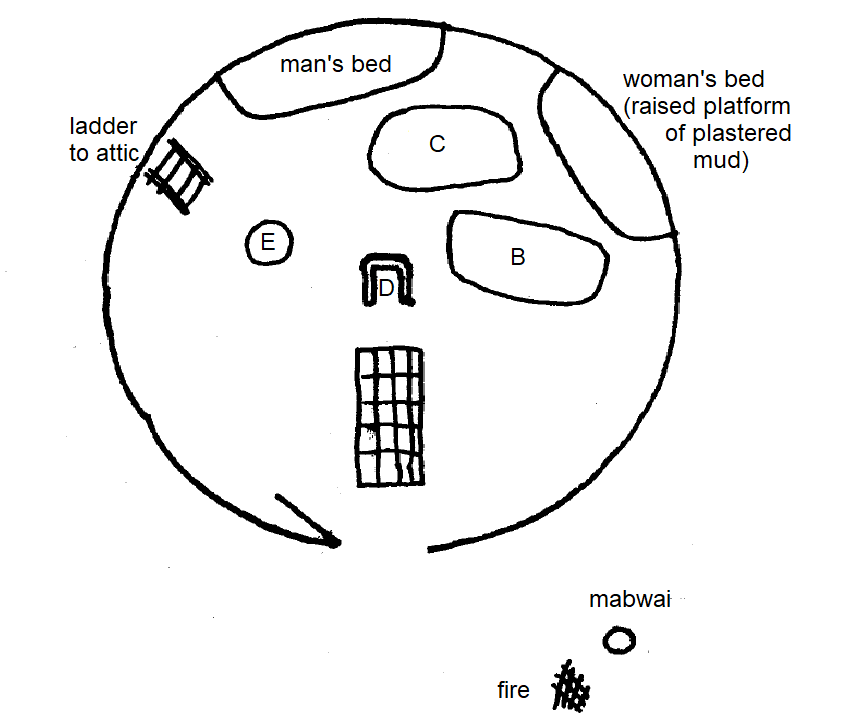

Plan of a House Used as a Kot ap Tumdo

B = "Arap Mogos" - an elder concealed under robes

C = "The wife of Arap Mogos" - a young man

D = Hearth whree the mecheita hoe is heated

E = Stool with nettles

While the initiands wait outside, some of the young men who have joined the others in the house relate what they have learned from each of the initiands. At the same time the kimusang’it is quickly dismantled. The two instructors come out and take the first initiand, kiboretiet, and lead him inside. He stands by the door and is told to perform what would normally be unthinkable acts, such as striking one of the men seated near the door. This he must try to do, but will be restrained by the instructor. He is then told to abuse one of the men, calling him an uncircumcised boy (ng’eta). He must do this without hesitation. He is then led over to the right rear part of the house where two men are concealed under piles of skins. The first man is known as Arap Mogos (the one who does not see or hear). He accuses the initiand of having slept with his wife. If the initiand hesitates to admit this, the second man, a young man speaking in a falsetto voice, takes the role of the offended woman and presses the interrogation, saying things like “oh yes, that's the boy who raped me in my sleep" or "that's the boy who jumped on me while I was bending over in my garden." During this questioning one of the men under the skins has a small stick in a muddy hole in the floor which is used to simulate the sound of coitus. The initiand must make a full confession here (which means also that he must steadfastly deny having had intercourse with a woman if that is the case). He is told by the instructor that if he has not told the truth everything will go wrong with his initiation. If he admits to having had intercourse with a woman he may or may not be required to identify her at this point. In any case the chances are very high that her husband would be present in the Kot ap Tumdo. If the woman's name were mentioned, there would be no further action taken against the initiand, though he is left to figure this out for himself.

When the men are satisfied that the initiand has told the truth, he is taken over to a fire in which a hoe of traditional Kipsigis manufacture (mecheita, used for digging salt licks) has been heated red hot. He is told to look up and told that he will now be circumcised. Various accounts differ on what is done next. In some cases the instructor takes the hot iron out of the fire and brings it close to the initiand's penis. At this point the initiand must not flinch. Nothing is actually done to him. In other cases he is told to walk through the fire, and that his foreskin will be removed as he does so. He must begin toward the fire, but will again be restrained.

Following this, the initiand is brought around to a stool covered by a large skin. He is asked to feel the stool and guess what is on it. Although he may suspect what is to come, he is not expected to answer correctly. The stool has been filled with more stinging nettles. He is told that he will now be circumcised. The initiand is then turned around, facing the instructor, who places his hands on the initiand's shoulders. Another man removes the skin and the initiand is forcibly seated on the stool. He immediately jumps up but is pressed down three more times. The initiand is then led back around by the door and taken outside, and the next initiand is led in.

Each initiand goes through this series of tests in the order of their file. All of this takes a long time and is not finished until about 3:00 a.m., when the initiands are finally drawn up again in line outside the Kot ap Tumdo. They are then led away into the bush to await the dawn.

Some young men assist the instructors in destroying the structures built in Kot ap Tumdo and removing all the equipment. The floor is repacked where it has been disturbed, and the house is left as it was before the start of the ritual. The plants are then scattered in the bush some distance away where they will not be found. The older men proceed down by the menjo to await the dawn. Many of them try to catch an hour or two of sleep wrapped in their blankets on the grass. Some might make a small fire inside menjo to warm themselves (it is quite cold at this hour, usually about 50° F., and often very wet).

The initiands are not allowed to sleep, but are kept sitting in the wet bush. The young men continue to interrogate them about their state of mind and 'brow beat‘ them in an attempt to shake the initiands‘ resolve. Should the men feel that any of the initiands is frightened to the point where he may lose his self-control during the operation, they tie a certain species of thin vine around his left ankle shortly before taking him to the operation. The underside of the leaves of this plant are covered with very fine spikes which cases a sharp painful swelling on contact with the skin, much like a wasp's sting or a typhus injection. This reaction continues for several hours (I know, I tried it on my arm). The use of this plant, as well as the stinging the boys have received all around their faces, limbs and back (and particularly around the genitals when seated on the stool), may serve a purpose similar to anesthetization by displacing the pain felt during the operation.

There is nothing to do now but wait.

The women who have gone home with their guests arise in the semi-darkness and come down near the menjo for the operation. The mothers and close female relatives of the initiands are decorated with wreaths of vines around their heads (as are the boys' fathers). When the first light of dawn appears, or as soon thereafter as the operator arrives if he has been to another menjo that morning, the word is sent to bring the initiands. The young men then rush the line of initiands down to the small clearing next to the menjo. Each boy is escorted by his father or older brother. The first step in the operation takes place immediately.

As they arrive at the menjo, the operator goes up to each initiand in turn and makes a small cut laterally on the top of the penis, marking where the foreskin will be removed. This takes just a few seconds for each initiand. This cutting is called kweret ap met (striking the head). A few informants stated that this was done before the initiands were seated, though in the cases I witnessed it was done immediately after they were seated. In any case, the initiands are hurriedly seated on the ground in a line with the first farthest to his right, and each succeeding initiand to his left. All of the men crush around in front of the initiands. Each initiand is seated with his legs spread straight in front of himself, firmly held down by older brother or other close male relative who has knelt behind him and hooked his arms, one over and one under the initiand's shoulders, while another man stands directly in front. The initiand has been told that from the moment he is seated he must look up and stare into this man's eyes and remain absolutely still and silent.

The women who have been lingering twenty or thirty yards away rush forward behind the line of initiands trying to get as close as they can. Except for the rare individual who is allowed, when very old, to learn all the secret rites of the other sex's initiation, women are not supposed to witness the actual operation. But it is recognized that the mothers of the initiands probably will see it since they usually succeed in pushing their way right up to the men and looking over the shoulders of the men holding their sons. No one actually steps aside for them or invites them closer; they simply shove through with more vigor than those around them.

The operator squats down in front of each initiand and quickly pulls the foreskin forward and removes it with a few strokes of the knife. The whole process takes no more than twenty seconds for each initiand, and the group is done in a couple minutes. The intensity of the moment is absolutely electric. All eyes are on the initiands. Although there are stories of initiands running away at the last moment, the men behind them have such a grip that it would be impossible for an initiand to break loose. To pass the test of circumcision successfully, each initiand must remain motionless and silent. Sometimes a young man will stand over an initiand with an upraised sword or club, drunk and trembling with emotion — someone who earlier told the boy that he will kill him before he will allow a coward into his age-set.

Immediately after the last initiand is circumcised, the operator stands back and declares the number of new men. There is an explosion of relief. The younger men break into a song telling of the courage of the initiands.6 On hearing this the women start rejoicing, shouting and ululating. The korosek fronds, which had been collected from the parents‘ houses, are given to the mothers of the initiands as a sign that they have successfully completed the test of circumcision. As the crowd breaks up, the women carry the fronds home and throw them on the roofs of their houses where they will remain until they decay or wash off.

Daybreak

The women are soon busy preparing for the feasts that will start later in the day. The fathers usually stay near the initiands for a short time to make sure that there are no complications. Many lie back on the grass emotionally exhausted. After a while most of the men leave with their guests to go to their homes where they drink fermented porridge and tea. As the day grows warm, and the weariness of the morning fades, there is a great sense of relaxation and joyful relief, and everyone is in top spirits for the parties that start around midday and last well into the next. At the home of each initiand a steer is slaughtered. Virtually every dish in Kipsigis cuisine is served in a bewildering order: fermented milk (mursik), raw meat, sweet tea (made with whole fresh milk, not water), fermented porridge, roasted meat, tongue, liver, etc. Young men drink directly from basins of cow's blood that are passed around, and through it all there is beer from an endlessly replenished pot in the middle of the floor. The beer and food consumed by the guests is easily the equivalent of one to two months’ supply for the homestead.

Meanwhile, the initiands are left sitting on the ground, their cloaks thrown over their shoulders. Each has a stout stick, about two and a half feet long, cut from the plant called tebeng'wet, placed in his right hand. He is told to refer to it as a spear (ng'otit) and to keep it with him at all times.7 They are also handed a short leafy branch of the lelecheret plant to be used to keep flies away from the wound. This is to be referred to as a fly whisk (kipsogorit, i.e. wildebeest, the tail of which is usually used as a fly whisk by old men). The initiands are told to keep pulling back the skin around the wound to present it from drying and scabbing.

It may also happen that as the initiands are waiting in the bush, after Kot ap Tumdo, to be taken down to the menjo, a boy who has not been a candidate and who has missed all of the ceremonies up to then may still “jump” into the line of initiands and undergo initiation. In 1966 I witnessed a circumcision ceremony at which the operator stood up and shouted muut! five!. Chaos ensued as father after father shouted, ang'wan! ang'wan! four! four!. One after another several men ran down the line of sitting initiands counting them off and being confused to find five. Finally someone pointed to the one in the middle and shouted "hey, who are you?" It was a young fellow who had got his older brother to shave his head, surruptitiously get a fur cloak, and help him sneak into the line as the initiands were rushed from the wet bush down to the menjo yard just before dawn. He had missed being anointed and blessed, missed undergoing the ordeals of Kot ap Tumdo and everything else. Now sitting there, bleeding, there was nothing to do but send word to his family that he was a member of an initiation group in seclusion.

And everyone had heard of the story of the two boys went off in the bush and tried to circumcise each other.

Shortly after this the operator arrived and became very angry when he learned what had been done. He started to raise his voice to the kwanda, but the kwanda quickly silenced him by saying that he would not tolerate any display of anger in his menjo (any serious dispute or fight would would have necessitated a ceremonial slaughter of a ram or he-goat to rectify the situation).

The operator then proceeded to perform the second stage of the operation on the four other initiands who were seated in a line before him. It took him an average of five and a half minutes for each initiand. During this time there were about a dozen men in the menjo yard, and a fair amount of coming and going between the yard and the beer party that was starting at the kwanda's house up the hill a hundred yards away. Only a few men bothered to watch the operator during the second stage.

The second stage of the operation is termed Timet, The Pressing (though it is almost never spoken of directly). The skin around the wound (where most of the foreskin has been removed) is pressed back and the exposed tissue is scraped with the knife, removing any white tissue and dried blood in the wound. Periodically during this the wound is washed with cold water. This is the "honey “that the initiands “drink” with the men. Everyone agrees that it is extremely painful. When the wound has been cleaned, a small longitudinal cut is made in the loose skin on the top or the penis, and this skin is then pulled forward and the glans forced through this cut.9 The effect is to neatly seal the wound, leaving a small opening underneath the glans for the wound to drain but otherwise leaving no raw flesh exposed. The Kipsigis claim that the effect of the second stage operation is to cause the penis to remain semi-erect (a very doubtful claim in my opinion) and to ensure that the erect penis will be straight "so that one does not have to use one‘s hands during intercourse.“

Throughout the second operation all of the initiands I observed remained immobile, though obviously in pain. They sat alone in a line. No one held them. Aside from the operator, no one even paid them any obvious attention, All of the men I questioned agreed that it would be of no significance if an initiand were to cry out during the second operation, but they are not told this until later. One of the men interviewed said that he lost a great deal of blood and fainted during the second operation and another reported that because of complications in his case the men slaughtered a goat and performed a small ceremony to insure his recovery.

During the next few days the initiands‘ wounds are checked often. Any man visiting menjo, and particularly the fathers, may ask to see the wound. Although several men in change of different initiation groups asked me for antiseptics and, in the cases I checked, app1ied them after a fashion, all of the wounds I inspected were septic for about a week after the operation. In a few cases, when men could not find regular antiseptics, they applied methylated spirits (which they also use for accidental cuts). The fact that this is very painful for the initiand was considered a fortunate side effect. In rare instances, I was told it may be necessary to take an initiand to the hospital if his life were in danger.10 Having checked that the convalescence would proceed normally, the men start to instruct the initiands in the rules of their seclusion. The rules which apply for the whole seclusion period are as follows:

- They are not to drink water,

- They are to talk only when spoken to by a man; they cannot converse with each other, or speak in ‘Swahili or English,

- They are not to make any unnecessary noise

- They are not to swear, to abuse each other, or to fight

- They are to move about only in pairs, and (after the end of total seclusion) one initiand and one man must be at the menjo at all times

- Whenever they enter or leave the menjo hut they must use the left door (the right is for men), and must hit each side of the door frame with their "spears" as they pass through

- They must sleep on their backs without any form of pillow

- While urinating they must always look up; they can only urinate on certain species of trees which dry quickly

Several other rules are given, though these apply only to the period of convalescence before the next ceremony. These rules are:

- They cannot kill any living creature

- They cannot touch food or eat with their hands

- They must call each other chebi (girl) and address each other by girls‘ names

(e.g. Chebkemoi instead of Kipkemoi) - They cannot call each other weri as they have in the past

(weri literally means son, but is used like “guy", "chap", "bro") - They must refer to their wounds as vaginas, and any blood (korotik) they shed must be called menstrual blood (sunonik)

- They must refer to a cow (teta) as a buffalo (soet)

- They must refer to a sheep or goat (artet) as a duiker (cheptirgichet)

- They must refer to a fly (kaliang'et) as a tsetse fly (sogoriet)

- They must refer to the staple food (kimiet, porridge) as tree bark (bertet)

- They are not to be seen by women and children

(this is partially modified in later stages of seclusion)

In the middle of the day the initiands are brought food prepared at the kwanda's house. They are fed for the first time in twenty-four hours. The food is given to them on a large piece of bark and they can touch the food only with a small stick which has had the bank stripped from it. They are also fed sour milk mixed with cow's blood (mursik ak korotik).. Although they now use tin cups some of the old men feel that this should not be allowed, and in some menjo groups one cow's horn is used as a gesture of traditionalism.

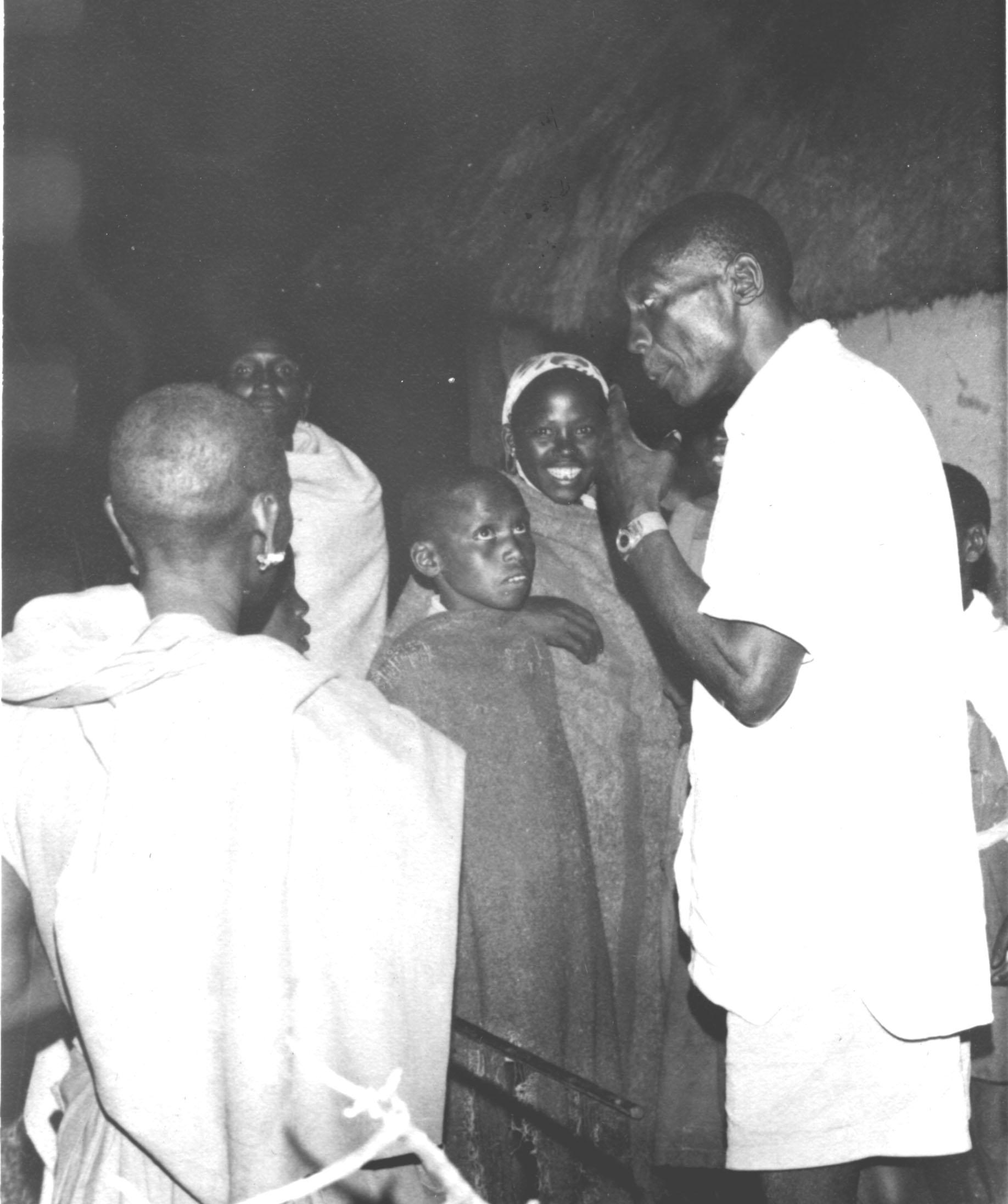

Initiands in Total Seclusion During the Recovery Phase

The state of total seclusion continues for about ten days or two weeks. Before World War II it extended in some cases for about a month. During this period the initiand does little more than sleep and rest. They are as well fed as possible. When all the initiands in a menjo have healed, they are ready for the next stage.

In the morning the initiands are put inside the menjo and the door is closed. They are then called forth one by one. Each is shown some tracts made by a calf and asked if he can follow them. He is told that one of his father's animals have been stolen and he is to recover it. The initiand is given a wooden club and, in some cases, a wooden stick to represent a sword or spear. A short distance from the menjo yard he meets a man armed with a shield and a club or iron sword (the initiands are escorted during the “tracking” to make sure they follow the right path). When this man, the "thief” threatens the initiand, the men tell the initiand to attack him. The initiand tries to hit the man repeatedly with the club, but the man chosen for this fight is skillful in defending himself with a shield and the initiands do not succeed in landing a blow (if one did he might easily break some bones). As soon as it is clear that the initiand is attacking in earnest, the men shout at him to desist, and he is taken away and the next initiand brought out. When all have participated, the initiands are told that from then on if any man troubles them they are not to fear him but should resist and to be prepared to fight for themselves.

After this the initiands are lined up in order and led toward the menjo yard. The first is taken into the yard and asked to kneel down, bend forward, and close his eyes. A young man then approaches with two handfuls of stinging nettles and reaching around from behind prees them against the initiand's face. After several seconds he removes them and the initiand is asked to open his eyes. One informant reported that they did not remain kneeling, but that he was made to crawl a few paces forward as the nettles were applied. Kipsigis explain that the purpose of this is to cause the initiand's eyes to be permanently bloodshot: men's eyes should be red and not white like those of women. In recent years the stinging has been made much less severe as many men feel that it permanently impairs eyesight which is much more critical now that most of the initiands are in school. Here, as in the case of beating the initiands, which goes on from time to time, the older men in charge of the initiands, especially the kwanda, must restrain some or the younger men who tend to be rather severe in their handling of the initiands.

Later the initiands are taken by their instructors to a stream where they dip their hands in the water, washing them for the first time since the start of their initiation. After this they return to the menjo and strip off their cloaks. They are told to crawl on all fours, imitating cattle, and to drink musarek, fermented porridge, out of a cattle trough. Then they are given tools to handle such as a machete, a knife, and an axe (viz Peristiany 1939:15). In the evening the initiands are shown a planet called taboita/taboiyat (the morning star) and are taught various constellations of stars.

After the Labet ap Eun ceremony, initiands are told that they can now wash their hands and eat with them. Instruction is started in the initiation song keyandaet before and after each meal. If any initiand does not know the song he may be switched by the men. The initiands are still secluded but allowed limited mobility in which they practice the physical skills of manhood. They make knobbed arrows for shooting birds and a walking stick. They are allowed to move away from the menjo, painted in white clay and wearing their skin cloaks, but they are not supposed to be seen by women or children. Most of this time is spent hunting small birds and animals. Some of them learn to secrete bits of white clay so they can surruptitiously drink water and then repaint their chins to avoid detection.

Initiand in Seclusion Following Labet ap Eun

During this period they are also told that there is an animal that will come to take them at night (much like the monster Chemosit who is used to threaten naughty children). The initiands are told that they can keep the animal away by singing the kayandaet song. Some young men make a bull roarer and whirl it near the menjo at night and shake the roof. A few initiands are apparently scared by this, but most recognize it as a sham. Quite possibly some boys actually guess what the bull roarer is (young herdboys make small ones out of flat seed pods and a length of sisal fibers, though if they are caught at this by a man he will immediately take it away from them). One enterprising man reported that while out hunting during this period of his seclusion he discovered the bull roarer hidden in some bushes not far from the menjo. Later the initiands are taught to whirl the bull roarer themselves.

The hunting period is now only about a week long because of the limitations imposed by the school schedule, but in the past it lasted one to two months.

Answer: You watch her when she goes to the bush to defecate. Go there later and take a little of her excrement and put it between two trees that rub together. Then every time the trees rub together making a noise, she will break wind uncontrollably.

Question: What do you do when red ants enter your house at night?

Answer: Gather some branches of kibirosit (a plant with red leaves) and heat the fIoor around the ants and they will go away.

Question: What do you do when you want to stop the rain?

Answer: Take a burning piece of wood from the hearth and stick it in the ground outside with the burning end pointing to the sky, and the rain will step.

Question: What do you do when you want to kill your father?

Answer: Wait until one of his cows dies, then take one of its ribs and bury it under the pile of goat dung sweepings outside the house, and your father will die in a few days.

Thus the initiands are taught what they can and should do, and what they should not do, in terms of supernatural or indirect ways of defending themselves socially. The men also tell the initiands that they must show loyalty to their kapchi, to their clan, and to their age-set. Proper patterns of respect are streed as well as the instructions mentioned above on the allowable limits of protecting one's own position. It is interesting to note that the men who take part in the Tienjinet ceremony get drunk before discussing these topics.

Prior to World War II, the period following Tienjinet was one of limited social interaction, in which the initiands were allowed to move about at a greater distance from the menjo. At this time they constructed straw masks, like hoods, (called a marangochet) that fitted over their heads and from which they hung the animals and birds that they had killed (see Peristiany 1939: plate VII). By the mid 1960s most menjo groups had dispensed with these masks, though in 1966 I did see one set of initiands near Sondu wearing them (but was unable to investigate further). While wearing these masks the initiands could be seen and could converse with people at a distance, but they were not allowed to call people by name or to identify themselves individually. They could chase small boys, order them about, or beat them (one informant said that they could even beat old men). They could break through fences wherever they went. At present all this has been sharply curtailed, and the period between Tienjinet and the next ceremony is at most a few days.

The initiands are then asked if all of them have played in water as children and if there is anyone who does not know how to dive under water. They are then led to a place in the stream where the young men have built a dam, creating a small pool. Underwater another kimusang'it tunnel with stinging nettles has been built. The initiands are led into the water and kneel down in line with their instructors at the front and back of the line, and place their heads under the surface. They then crawl through the kimusang'it, stand up, walk around, and repeat to complete four passages just as they did in Kot ap Tumdo. Most of Kipsigisland slopes from the Mau Forest to the east, with elevations over 10,000 feet, down to the west. The ridges are divided by a few rivers and many steams; there are no lakes or signifiant ponds, and almost no one has experience in sustained swimming. Several men commented that being in a tunnel, underwater, in a cold mountain stream, in the dark, was a difficult test of nerve.

After these challenges, the initiands are taken back to the menjo, stopping on the way to collect some small (inedible) yellow fruit called tug'ap labot which represent cattle in a variety of Kipsigis ceremonies and children's games. The young men accompanying them sing a song, called koiyo celebrating a successful cattle raid against the enemy.

Following Kayaet there used to be a period of a month or more during which the initiands, dressed in their masks, visited their parents' houses in turns, being feasted. This period has now been omitted (because of the limited time available during the school holidays), and within a few days initiands are led through the steps preliminary to their emergence from seclusion.

The initiands are then given thin branches13, known as mutulik, and told to go hit a woman or a girl with the stick to cast off their own uncleanliness (ke-chur nesek, to strip off the charcoal). It is interesting to note that when girls must do a similar thing they are to beat boys, but not men, but they are told they can beat a Luo man since he is uncircumcised. It is reported that for male initiations, members of certain clans must not merely hit a female with one of these sticks but must touch her genitals with his penis. It is also reported that a few clans require that their members carry out an actual rape. One informant who was initiated in a settled area north of Kericho was told during this ceremony to just take the stick out in the bush and hide it in the ground, rather than attack a woman with it. He explained this was because there were a great number of Kikuyu women in the area and the instructors were afraid that if one of the initiands attacked a Kikuyu woman unfamiliar with this part of the ceremonies, there might be an incident between members of the two communities.

After this is done the initiands destroy the partition in the menjo and abandon it. That night they go to sleep in their kwanda's house where they join the men in a beer party and for the first time are allowed to eat and drink as men in a sort of first communion.

Click here for other images relating to female initiation

The initiates are brought by the instructors up to the gate one at a time. The senior instructor stands near the gate on the other side from the initiate who is kneeling. A sister or other close female relative of the initiate is called forward to face the initiate through the gate The instructor then leads her and the initiate in shaking the central branches of the gate up and down while singing "Oyatwech oret ka tarech ririk" (Open the path for us, the tick birds are consuming us). This is sung four times for male initiates (and three for females). When the first initiate has had the gate "opened," he gets up and moves to the rear of the file; the next approaches the gate, his sister is called, and the process is repeated (the initiate does not actually pass through the gate). Some clans also practice an extra little ritual after the gate has been opened. The initiate places his foot on the bottom cross-pieces of the gate and the relative places her foot on top of the initiate's, and another chant is sung. Following the opening of the gate, the initiate's mother formally recognizes him and anoints him as in the beginning of his initiation. The newly initiated men are then welcomed to their homes.

Upon his coming out of seclusion, the young man assumes a patronymic name of the form "Arap ---". Arap is a formal contraction of werit ap, the son of, that proceeds every man's name.14 The second element is taken from one of his father's personal names, most commonly one of the father's childhood names.15

For the next day or two following Yatet ap Oret, the newly initiated men, or bogototik, go as a group from home to home where parties are held with the relatives and neighbors in honor of the initiates. The father takes the sirtitiet branch which his son has been carrying and cuts it down into a walking stick (tilet ap korokto, the cutting of the walking stick ), and rewards the son for his successful completion of initiation with the gift of an animal, usually a young bull or steer (tet'ap korokto, the cow of the walking stick ). The next day the bogototiot's head is shaved and he puts on the new clothes of a young man, which in the 1960s consisted of a new, white or lightly colored blanket, and a head scarf, usually a bright orange dust cloth. Carrying his new walking stick, he roams about with his mates, visiting the local shops where they act very arrogantly, pestering girls and pushing aside women and small children. Before World War II the young men then grew their hair into long braids dressed with grease and red ochre in a manner similar to the Maasai. In the past this was the time in which they would organize cattle raids against the Maasai (and vice versa following Maasai male initiations).

Bogogotik, January 1966

By the 1960s the whole period from Ng'etunatet to Yatet ap Oret covered just a couple days after which the bogototik had only a day or two before they had to again put on their school uniforms and return to their education.

The military aspect suggests a further analogy: one of the goals of the Kipsigis initiations, in the precolonial period, was to produce foot soldiers, not jet pilots. The situation was much like army basic training with universal conscription. The goal was to develop the skills and motivations appropriate to the military pressures on the society. These included not only the motivation to initiate cattle raids on other groups, but the willingness of one and all to respond immediately in defense of any Kipsigis. With the weaponry that existed (spears and shields, bows and arrows) military superiority was determined most directly by the sheer number of men in the field; maximum strength was achieved by mobilizing all able men. In such a situation each boy was to be trained to the same model, and unlike a pilot training program where ten or twenty may be "washed out" for each candidate who eventually completes the program, in the Kipsigis case virtually all candidates must succeed. This leads to a view of the candidate as someone who is passive, even captive, throughout the initiation: someone to whom things are done, whose own particular personal characteristics are irrelevant; someone who has to be taught the appropriate responses and who has to internalize them so that such response patterns will continue after initiation in the absence of any institutionalized powers to force compliance (the many references to both male and female initiates as cattle or calves is suggestive of this view). It also follows that efforts must be made to insure that the initiation is not unendurable physically and emotionally.

It is interesting, therefore, to note that while the Kipsigis male initiations do involve extreme pain and make great demands on the initiates emotionally, and that these ordeals and tests are recognized as a central aspect of the experience, nevertheless there are many elements that seem to be means of reducing rather than increasing such strain.

The events proceeding the operation, especially the ceremony in Kot ap Tumdo leave the candidates very tired and hungry, in some cases at least a bit dazed, and feeling the effect of the stinging nettles over most of the body. Perhaps, however, this is the best state for any initiands who may actually have trouble enduring the operation, or whose minds have been dwelling on the crisis they face. Only those with the most resolve, who have "jumped in", undergo the operation without such preparation. The fact that a few do so also indicates that they at least know the time of the actual operation and have some partial idea of how it is performed. It seems likely that although most candidates may be unaware of the details of Kot ap Tumdo, they are well aware that it is a preliminary ritual that does not really make the crucial difference. Similarly everyone stresses that the most important characteristic of an operator's skill is his speed that minimizes the period of time, while the women crush near, that the initiands have to endure the first stage of the operation in silence. These few moments are the only time in which the initiate is exposed to the possibility of abject failure. They have just come from a last minute reassurance by the operator and are unaware of the much more taxing second stage operation that occurs after their bravery has been established. The initiation is not simply a test of the boy's ability to endure pain, but at each of the various stages a test of his self-confidence in his ability to become a man as defined by his culture, which is another way of saying that it is a test of his trust in the men and what they will do to him. In this sense the many false trials in Kot ap Tumdo and in later rituals can be seen as acts which reinforce that trust.

The military aspect of Kipsigis male initiations appears to have been of most immediate importance in a situation of intertribal warfare, and this aspect cannot be easily separated from other parts of the ceremonies. The functional diffuseness of the initiations is directly related to the lack of structural differentiation of adult male roles. In the precolonial period no one was a "warrior" who was not also a "civilian.” There were no standing armies or central barracks, as found for example among the Zulu. Individual participation in cattle raids or campaigns against other tribes was motivated by the opportunities for individual gain as well as by “defense” of the tribe's position in the intertribal competition for resources. This individual gain was, of course, primarily in the form of cattle. 0ne's career in warfare was a part of one's career as a cattle owner, which was in turn part of one's career as a husband and father, and thus a man of standing in the community. It is not surprising, therefore, that there was a congruence between military virtues and civil and domestic virtues in adult male life, or that these virtues continue to be important, and to be stressed in initiations, despite the elimination of almost all intertribal hostilities. Among the still relevant behavioral patterns taught in initiation are such things as the judicious use of violence against women and children, the suppression of hostility between men, along with the propensity to react violently in cases of theft or insult16 and solidarity among men of the same age. The initiation ceremonies are concerned with teaching the general values that underlie correct adult behavior. On this level the Kipsigis do not believe that "the child is father of the man.” The message of initiation is, instead, that only those who already understand manhood can turn boys into men. One cannot make the transition by oneself. Manhood does not follow as a continuous development out of childhood.

Following this interpretation, one can consider the initiation ceremonies as a process of "thought reform" designed to alter the self-concept of the initiate to fit an ideal model of manhood. Although the initiation is universal, and thus compulsory, each boy does not become a candidate until he has expressed his willingness to subject himself to the ceremonies. He becomes more and more committed as the preparations develop. As his parents' speeches clearly state when they anoint him and he assumes the status of initiand (torusiot), he takes responsibility for himself from them, a responsibility which he then surrenders to the boiyot ap tumdo, the moterinik, his kwand'ap tumdo and others yet unknown. He thus enters initiation willing and committed to becoming a man. The ordeals of Kot ap Tumdo not only test his resolve and shock him physiologically, they also violate the interaction patterns that the boy has been used to in dealing with men. Fathers and sons never discuss sexual matters, but now he must reveal his experiences before his father and all the men of the community. He is told to abuse men and is in turn abused, in ways that would never occur in normal life. He is told, in effect, that the social expectations that he brought with him from childhood no longer hold. The operation destroys his physical childness. In the recovery period following the operations the initiate is in an intermediate status, no longer a boy, but not yet knit into a man. This stage is marked by role reversals (the initiates are ”girls") and redefinitions of common objects. These practices, combined with a great deal of false information that the initiates are given concerning what is coming next (which is always said to be worse than what they have already endured) can be seen as a further dissembling of their initial concepts. When the healing is complete, the initiates are ready to start learning to think as men, and to think of themselves as men. The instruction starts with the most basic things. In the labet ap eun ceremony the initiates are “taught” to handle tools and weapons. In the following period they practice the physical skills of manhood by hunting. In the Tienjinet ceremony the initiates are instructed in how to handle social tools (what to do and what not to do), and the social qualities of manhood. These they practice in a limited way in the following period of partial mobility. Having thus acquired, and to some extent internalized, these new definitions of manhood, they are given a final test and pass through the kimusang’it once again (in what appears to be a classic symbolization of rebirth). Following this they are taught the secrets of initiation, sworn to secrecy, and leave the menjo. Finally they "pass through” the "gate" opened by their relatives and are welcomed back into society in their new roles, with new names.

While this interpretation of the initiation cycle as a program for restructuring the initiates' conceptions of manhood is very brief, I think it could be expanded to fit a great deal of the observed details. It is a real question, however, whether Kipsigis male initiations actually result in any changes in the initiates' cognitive structure, or whether the ceremonies are simply symbolic statements of what is supposed to take place. It is my impression that there is a great deal of individual variation in the effect of the initiations; some men find it all so much nonsense and play-acting and report that they were only concerned with having the operation performed. Others reported that they felt they had undergone a change on a more psychological level. This variation has one of the factors that led to the decision to test hypotheses on the individual level.17 Much more detailed research than that reported here will be necessary before we can speak of the actual, rather than the presumed, effects of such initiations. 18 19

2 Some of the younger men claim that the general restriction against full intercourse with a girl is no longer observed. In any case, it would appear that the great stress on technical virginity of girls until initiation, which has been reported as the traditional norm, was never as closely observed as might seem. Men recognize that some non-virgins are honored as virgins by the women in charge of the female initiations, and that the girls‘ fathers are often content to accept the self-delusion involved.

3 It could happen that a fifteen year old woman is the third wife of a fifty year old man.

4 The tense mood at boys‘ initiations is in striking contrast to the parties on the night before girls‘ initiations. While the elders in the beer party are still quite reserved, outside the women are joyous and unrestrained.

5 Particular events in male ceremonies are often repeated four times; similar acts associated with females are repeated three times.

6 Informants reported that at this point the young men throw short sticks after the women and mock them according to the number of boys who have had relations with women. I did not notice this at the operations I attended.

7 The initiands are told to hit themselves sharply on the ankle with this "spear" if they start to have an erection.

8 Similarly in the girls‘ initiation it is possible for a girl to suddenly join without making any prior arrangements. At one party I law a "girl" who appeared to be at least twenty, and who was said to be a primary school teacher, suddenly join two candidates who were both decorated, just as the parents and other relatives started their speeches to the girls. No one raised any objections or questioned the girl, though a few young men, mindful of the relaxation of sexual regulations on initiation night, were obviously disappointed.

9 Descriptions of the operation with precise anatomical details can be found in Beadnell (1905) and Roles (1966).

10 In January, 1967 a girl died in Kericho as a result of complications following her operation (clitoridectomy), and another-girl was rushed to one of the mission hospitals where she recovered. I was not able to trace any definite cases of complications for male initiands, though it was reported that they occur on rare occasion.

11 One informant reported that prior to this a forked stick, kipsagat, was hung inside the menjo and the initiands were told that this would be used to remove a bone from the penis. On the evening of tienjinet each initiand was called out of the menjo one at a time and was told to stand still and look up. A man then pretended to remove a bone from the penis, applying cow's blood to simulate an operation.

12 While there are educated men today who are willing to discuss their initiations with an anthropologist, the Kipsigis insist that no one ever discusses these things in front of the uninitiated, and that even psychotics, who have been known.to babble on about sexual behavior in front of their mothers-in-law, never mention anything about their initiations.

13 "mutulik ...sticks of the kerundet tree which recently initiated girls carry when they go outside the hut", kerundet ...twiggy, green-stemmed perennial herb...used ceremonially and by youngsters for making switches. (Creider and Creider 2001: 209,106).

14 The accepted convention is to capitalize arap if it is used only with the patronym, e.g. Arap Koske, but not to capitalize it if it is proceeded by a childhood name, nickname, or Christian name. e.g. Kipkoech arap Koske, Chebusit arap Ng'asura. Many men now simply abbreviate their names, e.g. Joseph A. Maina, or drop the arap element altogether.

15 It is common to use the father's kainet ap musarek, the porridge name, which usually describes a feature of his birth, for example Kiplang'at, a boy born in the evening, or Kiptonui, a boy who fainted at birth. But the father could select his kainet ap kurenet, the name of the calling, the name given when he made his first cry being born, which is seen as a response to the old women asking which family member's spirit has returned. Thus a boy may also be named Kimarusoi (ki[p]- the male prefix, ma, not, ru, sleep; soi, grassland, the boy whose ancestor's spirit did not sleep [for long] in the grasslands before returning). Alternately the father can choose from any of his various praise names, ox names, or nicknames, for example Marindany, the man who loves cattle, or Mosonik, left-handed (literally "baboons"). The son of a man named Kiplang'at arap Bii could be called Arap Lang'at, or perhaps Arap Marusoi, or Arap Marindany, or Arap Mosonik. A man thus has a series of names to choose from when assigning one as his son's patronymic name, and he is asked what his son will be named by the officers of the initiation before the initiands leave seclusion. If a man has many sons, he may choose to give them different names so that it will not be obvious to those outside the community that he is so fortunate (since envy causes misfortune). After initiation a man uses his childhood name (usually of the form Kip-) only for identification in non-traditional settings; among the Kipsigis, men mentioned in conversation are referred to by nickname or patronym, and are further identified as necessary by age-set, clan, and place of residence. The use of the childhood names has greatly increased because of involvement with employment muster rolls, tax receipts, addressed by his boyhood name, though his father (but not his mother) may persist in this if he wishes. One of the most important steps in the divorce ceremony comes when the man and woman address each other by their childhood names, thereby ending any respect between them. For this reason men never use women's names, but refer to them by the forms Chept’ap Arap Kemoi (the daughter of Arap Kemoi), or Nebo Arap Maina, (the wife of Arap Maina), or Obot Chesang’ (Chesang’s mom, referring to one of her small children). 15 It is common to use the father's kainet ap musarek, the porridge name, which usually describes a feature of his birth, for example Kiplang'at, a boy born in the evening, or Kiptonui, a boy who fainted at birth. But the father could select his kainet ap kurenet, the name of the calling, the name given when he made his first cry being born, which is seen as a response to the old women asking which family member's spirit has returned. Thus a boy may also be named Kimarusoi (ki[p]- the male prefix, ma, not, ru, sleep; soi, grassland, the boy whose ancestor's spirit did not sleep [for long] in the grasslands before returning). Alternately the father can choose from any of his various praise names, ox names, or nicknames, for example Marindany, the man who loves cattle, or Mosonik, left-handed (literally "baboons"). The son of a man named Kiplang'at arap Bii could be called Arap Lang'at, or perhaps Arap Marusoi, or Arap Marindany, or Arap Mosonik. A man thus has a series of names to choose from when assigning one as his son's patronymic name, and he is asked what his son will be named by the officers of the initiation before the initiands leave seclusion. If a man has many sons, he may choose to give them different names so that it will not be obvious to those outside the community that he is so fortunate (since envy causes misfortune). After initiation a man uses his childhood name (usually of the form Kip-) only for identification in non-traditional settings; among the Kipsigis, men mentioned in conversation are referred to by nickname or patronym, and are further identified as necessary by age-set, clan, and place of residence. The use of the childhood names has greatly increased because of involvement with employment muster rolls, tax receipts, addressed by his boyhood name, though his father (but not his mother) may persist in this if he wishes. One of the most important steps in the divorce ceremony comes when the man and woman address each other by their childhood names, thereby ending any respect between them. For this reason men never use women's names, but refer to them by the forms Chept’ap Arap Kemoi (the daughter of Arap Kemoi), or Nebo Arap Maina, (the wife of Arap Maina), or Obot Chesang’ (Chesang’s mom, referring to one of her small children).

16 This tendency to immediate retaliation among younger men persists and usually leads to situations requiring community action, rather than leading to litigation in the local government courts. On the other hand I know of instances in which an elder has shown remarkable restraint when affronted.

17 It should be noted, however, that responses to the question "Do you feel that your initiation changed how you thought about yourself?” did not pattern according to expectations.

18 The two most relevant studies of which I am aware are still in progress. They are "The effects of initiation on cognitive styles“ by J. W. M. Whiting and J. F. Martin, and "The impact of male and female initiation on the self-image of adolescents“ by J. D. Herzog. The first involves testing male adolescents in seven Kenyan communities (including Kipsigis), the second involves a sample of Kikuyu adolescents. Both studies are reported in Whiting and Whiting (1970).

19 D. K. Kiprono (Arap Arusei) has written a detailed description of his initiation as a Keyo, which is very similar to the Kipsigis ceremonies described here. See Welbourn (1968).

Female torusiek (initiands), with their moterinik (instructors) in later stage of seclusion

Mabwaita for a Female Yatet ap Oret Ceremony, 1966

The line of new initiates approach the ormarich gate, Female Yatet ap Oret Ceremony

Close-up of initiates

Relatives 'opening the gate' - recognizing the new woman emerging from seclusion

Chebkelelik (The shining females), newly initiated 'debutantes'