SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

The basic dimensions of present Kipsigis social organization have been described in detail by Manners (1967) and will be discussed here only in brief. This is followed by a detailed examination of the nature of the family unit and a discussion of homestead and community organization drawn from my census and genealogical data from the community of Kapsuswek. This material supplements previous accounts of Kipsigis social organization1 and deals with that aspect of the society, the social environment of the child, which is most relevant to the psychological variables of concern in this study.

The formal aspects of Kipsigis social organization can be ordered along the dimensions of descent, age, and locality.

The Kipsigis express common patrilineal descent, beyond specific genealogical ties through known individuals, in terms of common membership in a clan2 or oret (plural, ortinwek; the word also means path or road). Various clans are said to be of autochthonous Kipsigis origin, or to be common to several Kalenjin groups, to be of specific Nandi origin, or to be identical to ortinwek known by other names among the Nandi, to be derived from the Okiek (Kalenjin-speaking "Dorobo" hunter-gatherers of the high forest zone), or from Gusii or Maasai people incorporated into Kipsigis society during the precolonial period.

A common form of a clan name is of the type Kapkomosik (kap-, the house of; Komosi, a personal name; -ik, the plural ending used with nouns referring to people). But many, perhaps most ortinwek names do not point to a presumptive ancestor (e.g. Kapsoenik, the house of buffalos). Even among those clans whose names incorporate a personal element, there is little attention paid to an individual ancestor as an historical or mythical personage, and no attempt is made to trace a line of descent from the clan's originator to its present members.

The description of ortinwek as "clans" in English has presented several difficulties, arising in part from the fact that the term oret is used to denote different degrees of inclusiveness. Many clans are recognized to be divided into a few "houses" (korik) though these sub-division names are rarely heard. In other cases, however, sub-division names are the ones most frequently used; for example many people identify their oret as Kapsoigoek although it is general knowledge among men 3 that those people, along with member of Kapchebulungu and Narachek are all members of one oret, also called Narachek, which is the exogamous unit.

Peristiany (1939:118) speaks of clan, section, and subdivision, only the last of which, if the clan is in fact subdivided, is exogamous. He applies the term kot-ap-chi (discussed more fully below) to the exogamous unit, reserving the term oret for wider, non-exogamous groupings identified by association with a totemic "animal" (tiondo). Manners, however, takes the recognition of exogamy as the criterion for his use of oret. The primary sources for the Nandi show a parallel disagreement in the use of terms: Hollis (1909:4-6) translates oret as both clan and family, the letter being a subdivision of the former. In Hollis' terminology the family, but not the clan, is the exogamous unit. Huntingford (1953:20) interprets the term oret specifically as the exogamous unit, which he calls the clan. In fact, although the Kipsigis recognize that some ortinwek are the outgrowths of antecedent categories (fission is perhaps the wrong word here since the separation arises out of the attenuation of common interests among a large number of widely dispersed homesteads, rather than a split along any genealogical lines), these subdivisions are seen to vary case by case, and there is no clear hierarchy of levels in an abstract sense such as has been described for segmentary lineage systems.

Not only are the upper limits of some ortinwek vague, but the critical feature, the range at which exogamy should be observed, is subject to ambiguity and differences of opinion. Thus there are clans which were said to have been "of one house" or "siblings" in the past but which now intermarry. Orchardson comments (1961:15):

There are also cases in which only a few older men, perhaps because of their numerous affinal ties, realize that two named categories are subdivisions of what has been considered an exogamous unit. One informant, over seventy years old and unusually interested in such matters, reported that it was not altogether rare for a marriage, particularly by elopement, to occur between members of two ortinwek which the old men still considered too closely associated to intermarry. As Orchardson (1961:15, writing before 1929), Peristiany (1939:123), and Manners (1967:245) have all noted, the subject of clan affiliation is quite secondary in most matters, is little discussed, and not closely followed beyond the range of one's significant affines. Within that range, however, an individual is related to members of a large number or clans, and a key feature of Kipsigis society is the classificatory expansion of kin terms via clan affiliation to connect to new acquaintances or new neighbors: 'Oh, you belong to Kibaek. My brother married a Kibaek woman. Hello, brother-in-law! ('Ochamege, kapyugoi!').

Clan affiliation is one of the central subjects of a marriage negotiation (koito) in which all parties must be satisfied that not only is there no question of violating clan exogamy, but that there is no unresolved homicide, or any pattern of infertility or unusual infant mortality involving marriages, between the two ortinwek. Further, it must be determined that the two people to be married are not cognatically related within the last few generations, and for these purposes potentially common ancestors are identified by the combination of name, locality, age-set, and clan affiliation. Since clans are not localized groups. and most Kipsigis marriages tend to be between families who live within a few miles of each other and know each other quite well, marriage negotiations usually do not require extensive discussion of clan affiliations. Still such matters must be checked; I know one case of a young man who traveled quite far from his home community to pay court to a young woman he had met in Kericho town only to discover during the opening pleasantries of his visit that her father was a kinsman.

When asked "To which clan do you belong?" (I bo an ora?), the majority of men will respond with the name of the descent category which they recognize as the largest exogamous groups.4 In this sense Huntingford's and Manners' use of the term oret is perhaps the best reflection of the everyday use of the term by the Kipsigis if it is remembered that this usage contains a good measure of ambiguity.

In the case of clans, as in the case of virtually every Kipsigis social category or group, membership is determined ultimately by local concensus. If one moves, such matters can always be adjusted if they prove inconsistent with the local concensus in another area. Questions of clan membership, age-set membership, community membership, and the like are resolved on a local, ad hoc basis. Membership in any group, i.e. one's social identity, ultimately is dependent upon present or past behavior (especially during initiation).

There remain some ambiguous aspects of descent among the Kipsigis that will probably never be fully understood because of historic changes. One is the question of the "totemic" nature of clans (Peristiany 1939,117: Manners 1967, 245). The situation may be described briefly as follows: many men, particularly older men, report that their "clan" (which may or may not be an exogamous unit) "has an animal" or two or more animals. An animal (tiondo, the term excludes domesticated species) in this sense may be a cockroach or a bird as well as a lion or a gazelle. It is possible for two intermarrying clans to recognize the same animal or for two men in the same clan to recognize different animals. These considerations apparently have little or no significance today. Even the oldest men could not explain what the system of clan animals was all about, and showed no interest in such questions. The majority of younger men are vague about their own tiondo affiliation.

In addition to membership in a clan (oret) and totemic identifications of some sort, each Kipsigis man in the pre-colonial period recognized his membership is one of four boriosiek (singular, boriet).5 Membership in a particular boriet was inherited from one's father, though a man could arrange a ceremony placing a son in a different boriet from his own (just as he could also assign his sons different patronyms). Thus all members of one clan were not members of the same boriet (cf, Orchardson 1961:11; Peristiany 1939:162. Manners (1967:247) discusses the lack of a simple correlation between oret and boriet in some detail. In the past Kipsigis warriors organized offensive units into four lines (kwanaik, singular = kwanet), each composed of the members of one boriet. For this reason most authors translate boriet as "regiment" (Manners suggests "phratry").

It appears that during the original Kipsigis expansion into Kericho District the boriosiek were associated with specific geographic areas, as they were among the Nandi up to the twentieth century (Huntingford 1953:8).6 As the process of expansion and migration continued among the Kipsigis, members of each boriet were to be found in every local area (Peristiany 192=39:162).7

The main function of the boriosiek, to mobilize warriors in distinct fighting units, was dropped after a disastrous battle with the Gusii in which the enemy concentrated on one kwanet and annihilated it.8 After that it was decided to mix the members of the boriosiek in each line of battle. Since then the boriosiek system has not served any real function. Today most younger men do not know their boriet affiliation.9

| AGE-SET | Sub-Set | Dates of Initiations |

|---|---|---|

| KORONGORO | Kipkoimet | 1838a - |

| Kiptormesendet | ||

| Kibelgot | - 1859a | |

| Kimarare | - 1858b | |

| KAPLELACH | Kiboloeng' | |

| Kimutaiywet | ||

| Kimasiba | ||

| Kebebuja | 1891 | |

| KIPNYIGE | Kipsilchoget | 1896c - |

| Tabarit | ||

| Kiptilosiek (Cheptechoret) | ||

| Kiptilgarit | 1901 | |

| NYONGI | Kosigo | 190? - 1910 |

| Kirsirgot | 1911 - 1915 | |

| Blu | 1916 - 1919 | |

| Mesiewa | 1921 - 1922 ? | |

| MAINA | Siling ("Shilling") | 1922 - 1923 |

| Chemorta | 1924 - | |

| Silobai | 1928 - 1929 | |

| CHUMO | Kimingiet | 1930 - |

| ------- | ||

| ------- | ||

| ------- | 1945 | |

| SAWE | ------- | 1946 - |

| Lesebet | 1952 - | |

| ------- | ||

| Kibago | 1964 - 1965 ? | |

| KORONGORO | ------- | 1966 ? |

a These dates are from Orchardson (1961:125)

b Orchardson's dating, based on the sighting of a comet.

c Orchardson gives the opening of Kipsilchoget as 1880. This was the first initiation group after the battle of Mogori, or Saosao, which Ochieng' dates to 1981 (1974:130). My estimate is based on data from one of the last survivors of Kipsilchoget.

The age-sets are arranged in a cyclical fashion so that the next age-set to follow Korongoro will be Kablelach. It takes over a century for the age-set system to go full cycle. Recruitment into an age-set is by initiation at adolescence. All initiates of 1955, for example, automatically became members of Sawe and will remain so throughout their lives. Membership is not determined by chronological age per se, and it is quite probable that some of the first members of Sawe were born before some of the most junior members of Chumo.

The Cycle of Age-Sets Among The Kipsigis

Prior to the twentieth century a period of several years separated the closing of one age-set and the opening of initiations to form the next. The transition between age-sets was marked by a ceremony, saget ap eito, the slaughtering of an ox, in which the age-set that had been undergoing initiations was declared complete and assumed the status of senior warriors, the age-set ahead of them removed their markers of warrior status and donned the emblems of elderhood, and the way was cleared for beginning initiations of a new age-set of junior warriors. In 1923 the neighboring, closely related Nandi plotted to turn the mass gathering of warriors at the next saget ap eito into a rebellion, but the colonial authorities were tipped off. The leading figure was arrested and sent into exile and the uprising collapsed (Huntingford 1953:43). Thus the last saget ap eito ceremonies among the Nandi, and I believe among the Kipsigis, were very early in the twentieth century. Since the mid-century, if not before, initiations have been held annually. Among the Kipsigis age-sets were normally divided into three major and one minor sub-sets. Unlike the same units among the Nandi, where they are known as mostinwek, fires, and given the same four names in each age-set (Huntingford 1953:59), Kipsigis sub-sets are given unique nicknames referring to historical events that marked the time of their seclusions.10

Huntingford, Orchardson, and Peristiany reviewed the data on oral traditions with the hope of establishing the periodicity of transitions and thus a chronology of precolonial history, hoping to correlate the history of local events, whose sequence was remembered in terms of age-set activities, to western calendar years. Unfortunately they focused on the precolonial situation, about which they had incomplete and contradictory data, and failed to see the significance of the fact that age-set transitions have continued to occur despite the loss of the saget ap eito and a closed period. The issues between them, therefore, remained unresolved. I discuss the intricacies of this debate and present a reanalysis of age-set dynamics based on my own fieldwork in two separate papers, Kipsigis Age-Sets: Coordination without Centralization, and The Extent of Age-Set Coordination Among the Kalenjin. It is sufficient to note here that an understanding of the system depends upon the realization that all age-set transitions are made by concensus arrived at by word of mouth without centralization of information or decision making in any appointed leadership, that transitions are not tied to any fixed number of years but are provoked by social pressures leading to local decisions which must then be coordinated, that such changes take time, and that ultimately the cohesion of the system depends upon the existence of ambiguity and retroactive adjustments at some times, in some places, and for some individuals.

One of the most important rules associated with age-set membership is that a man may not marry the daughter of a man belonging to the same age-set. Orchardson states that the saget ap eito "was not for the purpose of handling over the rule of the country from one set of warriors to another, but rather for determining publicly exogamy of generation" (1961:14). The punctuation of age-sets by saget ap eito ceremonies in various areas was necessarily approximate, and at any given celebration both recent initiates and those about to be initiated could take part (Orchardson 1961:13). The minor sub-sets, which were the ones being formed during these transitional times, provided the necessary leeway, for although they were considered the end of the age-set approaching completion, their members could, at a later date, declare themselves to be among the first members of the new, junior age-set.11 Thus one man I know initiated in the marginal Chumo/Sawe sub-set defined himself as Sawe in order to marry the daughter of a senior member of Chumo. These are of course individual decisions, locally accepted. There is no way they could be standardized; indeed such flexibility in specific instances is necessary to maintain the overall standardization of the age-set system.

Today, with the elimination of the old military organization and the saget ap eito ceremony, there is no organized age-grade of warriors nor any tribal-wide formal symbolization of when a man becomes a junior or senior elder. Although the term murenik (young man) and boiyot (decision maker or elder) are still used, their application depends upon the specific conditions of a man's life. With the dissolution of the traditional formal statuses of the age-grades, the age-sets have ceased to function as any sort of corporate units but remain social categories which serve to define patterns of interaction.

There are many explanations of the functions of East African age-sets which have been advanced. Most obvious is the observation that the age-set system mobilized the man-power of the tribe very effectively for intertribal warfare, while at the same time serving as a formal justification for the gerontocratic aspects of domestic politics.

Several authors have also noted that the behavioral norms associated with the age-sets "cut across" norms related to kinship or locality, and that is some cases a young man is more responsive to his age-mates than to his father. Peristiany also speaks of the ibinda as a "regulator of social behaviour" (1939:39) and discusses briefly the patterns of respect between generations defined in terms of age-sets (members of a senior age-set, for example, are often addressed as "father," bomong'o). The primacy of age-set roles over kinship roles in daily social intercourse with people outside the immediate family is related to the rather high incidence of polygyny among the Kipsigis. Since it is not at all rare for co-wives to be many years apart in age, it very frequently happens that people who are of the same generation, genealogically, are often of completely different generations chronologically. If one attempts to chart the genealogy of more than a few people with a vertical scale representing actual age in years, the task soon becomes impossibly complex, and quickly reveals the ridiculous situation which would result if people addressed their less immediate kin (cognates and affines), and followed the patterns of etiquette associated with such terms, according to strict genealogical relationships. The use of kin terms according to age-set membership is thus the common sense solution.

The settlement pattern among the Kipsigis has been, since the precolonial period, one of dispersed homesteads. Houses were built on higher ground (and still are within the range of available land). Thus dwellings tended to be scattered on hilltops and along ridges, with most of the gardening and grazing of domestic animals on the slopes. Population growth and land enclosure have resulted in the establishment of homesteads on all levels of a hillside throughout most of the district. The shape of the typical farm is roughly trapezoidal, narrower in width than in length down the slope. Farms, and fields within farms, are hedged with thorn bushes, sisal, or cactus (depending on the moisture of the soil). Even today the pattern of dispersed homesteads runs right up to the edges of the towns and trading centers scattered throughout the district (all such towns are intrusive).12

The basic local group among the Kipsigis is called kokwet (plural = kokwotinwek). This may be described briefly as the group of neighbors who interact on a daily basis, who recognize obligations of mutual aid and cooperation, and common responsibilities in settling disputes. A kokwet might also be defined as the social range within which women form cooperative groups to do the more onerous chores of gardening, men join together to plow, raise houses, drink, gossip, and share lunch, and children find their regular playmates. Although the host at every beer party has the right to invite or exclude whomever he wishes, one can usually assume a standing invitation at the other homesteads within one's kokwet.

The men of the community meet in public council (also called a kokwet) to settle disagreements within the group. A meeting of the kokwet may also take up matters between members of the same family if they affect the general community or if one of the persons involved has requested them to do so (one's neighbors may on the other hand decide that the issue is so much dirty family linen and refuse to hear it discussed in public). Decisions are by consensus, with the younger men leaving most of the talking to their elders. The decisions of a kokwet are enforced, to the extent that they are enforced at all, through informal social pressure.13 There are no formal offices within the kokwet; the term boisiek ap kokwet means simply the elders of the community, those men who are most influential among their neighbors. One must be an elder to command influence but it does not follow that all old men are influential.14

Because of the settlement pattern, the area occupied by a kokwet can generally be described as a hill or elevation bound by creeks or low land. This, however, should not be taken as a formal definition. Such factors as local population density as well as topographical features influence the size of the kokwet. The mean number of homesteads in a kokwet is probably not over forty. The term kokwet is also used in general conversation to refer to the land occupied by the community, though the term koret refers more specifically to land area rather than people. Koret, however, can also mean the wide area of a group of neighboring kokwotinwek.

The names of particular kokwotinwek are best understood as references to location that do not imply clearly delineated areas that can be readily mapped. Unlike the official government "village" designations, several of which comprise a sub-chief's jurisdiction (a "sub-location"), the place names in common use in Itembe, as elsewhere, refer to sites such as "by the yellow acacia trees" or to particular hills. They are not all on the same level of specificity, and need not be referring to mutually exclusive areas.

Inasmuch as a kokwet is defined in terms of patterns of interaction, it is quite possible for a man on the edge of a kokwet to be considered a member of it, even though his neighbor whose farm is between his and the rest of the community prefers to consider himself a member of the next kokwet. Similarly, there are no membership rolls for the public councils nor any idea of where to draw the line geographically between members and non-members. People who are affected by the issues at hand have the right to speak. It also follows that men of different generations, having different circles of friends, will have slightly different conceptions of the boundaries of the community.

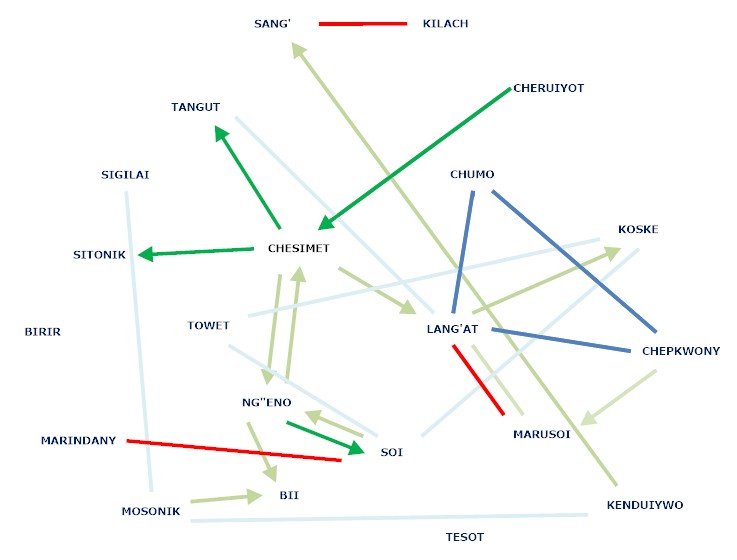

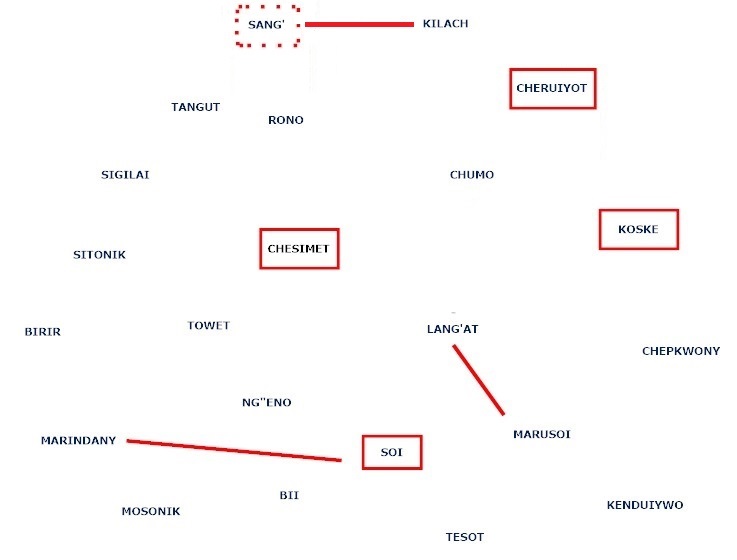

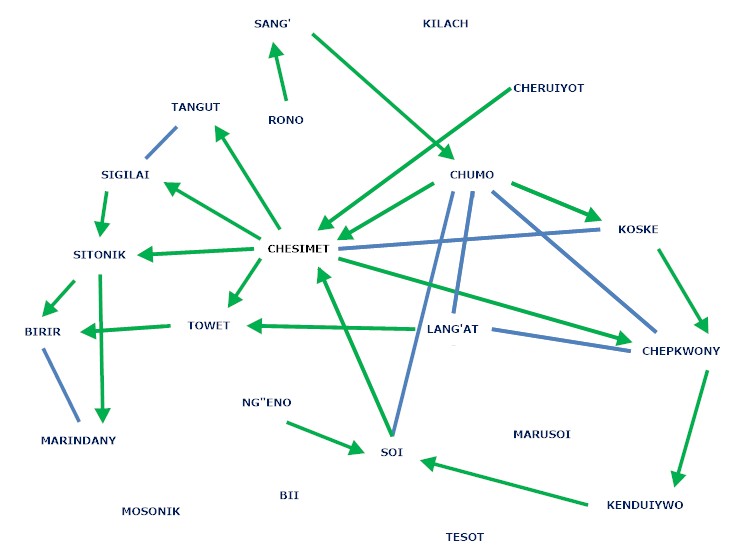

While the above sketch is in complete agreement with earlier accounts, previous authors have not investigated in detail the role of kinship in defining and uniting the people of a kokwet. From a closer look at the data from one kokwet, Kapsuswek, it can be seen that in daily life the categories of neighbor, friend, and relation fuse one into the other.

African pastoralism involves an intimate interrelationship between specific people and specific animals, between family and herd. Cattle, as opposed to gardens, hunting rights, or trades and crafts, reproduce themselves in a very limited, direct, and continuous way. Thus access to cattle is primarily determined by membership in one's family of origin, i.e. being born into a cattle owning family, and secondarily by exchanges with other cattle owning families (through marriages involving bridewealth). In such societies cattle and kinsmen (or more exactly rights in cattle and kinship relationships with other people) can be transmuted one into the other. A man who controls large numbers of cattle is widely respected not simply for his material wealth, but because his cattle are the manifestation (both the cause and the result) of his being more widely involved in the network of kinship.

While the above comments refer to a generalized model of African pastoralism, and the Kipsigis today are not primarily a pastoral people, nonetheless and understanding of the relationship between people and cattle is necessary for any discussion of traditional (precolonial) Kipsigis family organization and how it has changed in recent years.

It is not clear whether the Kipsigis, or the undifferentiated proto-Kalenjin people of centuries ago, were ever pure pastoralists like certain groups of Maasai. There is some evidence to suggest that some horticultural practices were not adopted until the Kipsigis moved into what is now Kericho District (Huntingford 1950:92). In any case, prior to the twentieth century introduction of maize, plows. and land enclosure, agriculture among the Kipsigis consisted of millet and vegetable gardening carried out by the women. Men devoted their attention to cattle, to offensive and defensive warfare (primarily focused on cattle raiding), and to community affairs. Cattle were an essential part of every household's economy, and thus also its social standing and, ultimately, its existence. In sharp contrast to animal husbandry, agriculture supplies few metaphors to Kipsigis thought and has little ritual associated with it. The precolonial situation is best characterized as pastoralism practiced at an unusually high density made possible by agricultural products derived from the fertile hill zone. In comparison to the more obviously pastoral groups, such as the Nuer, Karamojong, and Turkana, who practice hoe agriculture in less favorable low areas, Kipsigis homesteads were relatively small, representing one man and his immediate dependents, but closely aggregated in relatively continuous and permanent communities. Defense was based on high densities and a readiness of all able-bodied men to take arms, while the aggressiveness instilled among younger men through initiation secured abundant grazing in the adjacent grasslands.

Despite the enormous changes in the last hundred years, the ideology of Kipsigis social organization at the time of this study was still, for the vast majority, intimately related to cattle. Even with the increasing acceptance of modern economic pursuits noted by Manners (1967), particularly cash crop farming by the men and dairy production involving European strains of cattle (which were not used as a medium of exchange in the network of kinship), few men have divorced their social careers from the old patterns of pastoralism. Of course change has been greatest among the very few holding salaried positions involving cash incomes (which may be a hundred times the cash controlled by the average man). But almost all of the Kipsigis in mid-twentieth century could be described as peasants (cf. Fallers 1961); while not pure subsistence farmers, the members of a typical homestead were still the direct consumers of most of the produce from their garden and herd. It was not unusual in the 1960s for a shopkeeper in a small trading center to convert his profits into more cattle, another wife, and if possible more land. The situation among people who have been resettled on former European estates is also illuminating. Although indigenous cattle (aside from oxen) were forbidden on the resettlement schemes, and the official policy was one of modern commercial production, most settlers maintained their herds of native cattle with relatives back in their home communities in the former reserve. The economic contribution of such cattle to the new homestead is insignificant. It is quite clear that the cattle were maintained as a traditional form of capital investment and as a social investment guarding one's position in the home community.

As discussed in the Preface, there have been transformative changes in Kenya in the last fifty years. But as I have argued elsewhere (Pastoralists With Plows: Cultural Continuities Among the Kipsigis of Kenya, in the 1960s the large majority of Kipsigis participated in the cash economy in order to subsidize native cattle and the social and cultural systems expressed through cattle. Among the plows, primary schools, tractors, trucks, and buses, the Kipsigis continued to keep large numbers of native cattle. The figures from Kapsuswek, while admittedly from the soin grassland zone, are still surprising. Data from twenty-six homesteads (collected in 1966 and 1967) show 2l9 people and 575 head of cattle, an average of 2.6 cattle per person. Homestead herds ranged from 13 to 32 head. In comparison, Evans-Pritchard's estimate for the Nuer, whose herds were still depleted by rinderpest at the time, was less than one and a half cattle per person (1940:20). Thomas gives figures suggesting about three and a half cattle per person for a Dodoth neighborhood (1965:22). 1952 government figures for the Pokot, who are an example of "pastoral resistance" to modernization (Schneider 1959) work out to "an average of 10 to 20 head of cattle per adult man in the main pastoral areas and an average of from 2 to 5 head in the more heavily agricultural areas" (Schneider 1957:279). The numbers for Kapsuswek comparable to the first figure are 17.4 cattle per married man (including dependent sons) or 22 per homestead. I do not have figures for the Kipsigis highland areas but they are certainly higher than those cited for the Pokot.16

Brothers, meaning full brothers or half-brothers, members of the same kapchi in a wider sense, indeed any two men sharing agnation, share a common moral position. They are responsible for each other's obligations, debts, and transgressions.

Everyone is aware of close agnatic relatives beyond the cattle sharing group, and such people (if around) are shown special respect (invited to a child's initiation or marriage, for example). But there is no crucial reason for tracing agnatic ties beyond those in one's father's generation, which one naturally becomes aware of in growing up. Hence the lack of interest in tracing genealogies noted by several authors. Effective groupings involving descent focus around specific important (living or recently deceased) individuals, which is operationally the same as saying they focus around the control of specific cattle. Because of the variety of circumstances that arise in the life histories of a series of closely related people, there is no simple, universally applicable definition of what constitutes a cattle-sharing unit, and the term kapchi is thus used with a flexibility roughly analogous to the American use of the term "family." To attempt to pin down the term kapchi to mean either the cattle-sharing unit or a kin group on some specific genealogical level within which agnatic ties are traced would be an abstraction so far removed from the actualities of life as to hinder rather than aid comprehension of Kipsigis social organization.

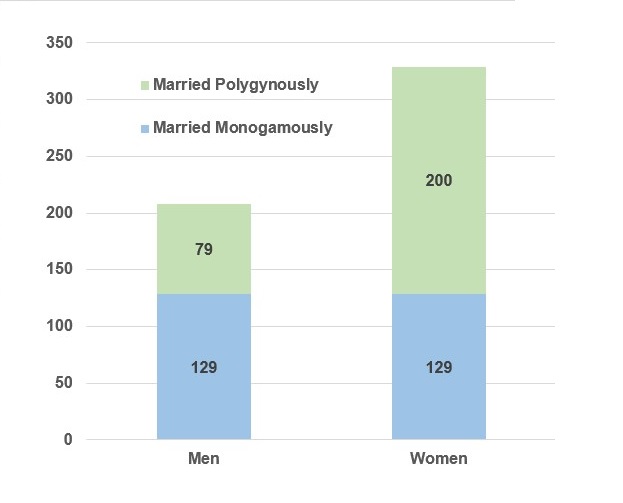

The Rate of Polygyny among 329 Marriages

Prior to the cash economy there was a clear upper limit on individual consumption. The primary resource, cattle, was to be used to support people. A man with twice as many cattle as his neighbor was expected to support twice as many people. Since the primary method of acquiring responsibility for others is through marriage, a man rich in cattle was expected, indeed was under a moral obligation, to marry additional wives, no matter his age. The system of polygyny that evolved, which assigns rights in particular cattle (property) to particular people (households), has been termed "the house-property complex" (Gluckman 1950). The principles, as practiced by the Kipsigis, can be stated simply (and will be discussed in detail below).

There are three main ways in which a man can acquire cattle (plus a variety of special means that usually involve only one animal at a time). The first is through direct inheritance from one's father. The second is through bride-wealth. The third, which involves rights to use but not ultimate ownership, is through loan arrangements with cattle partners.

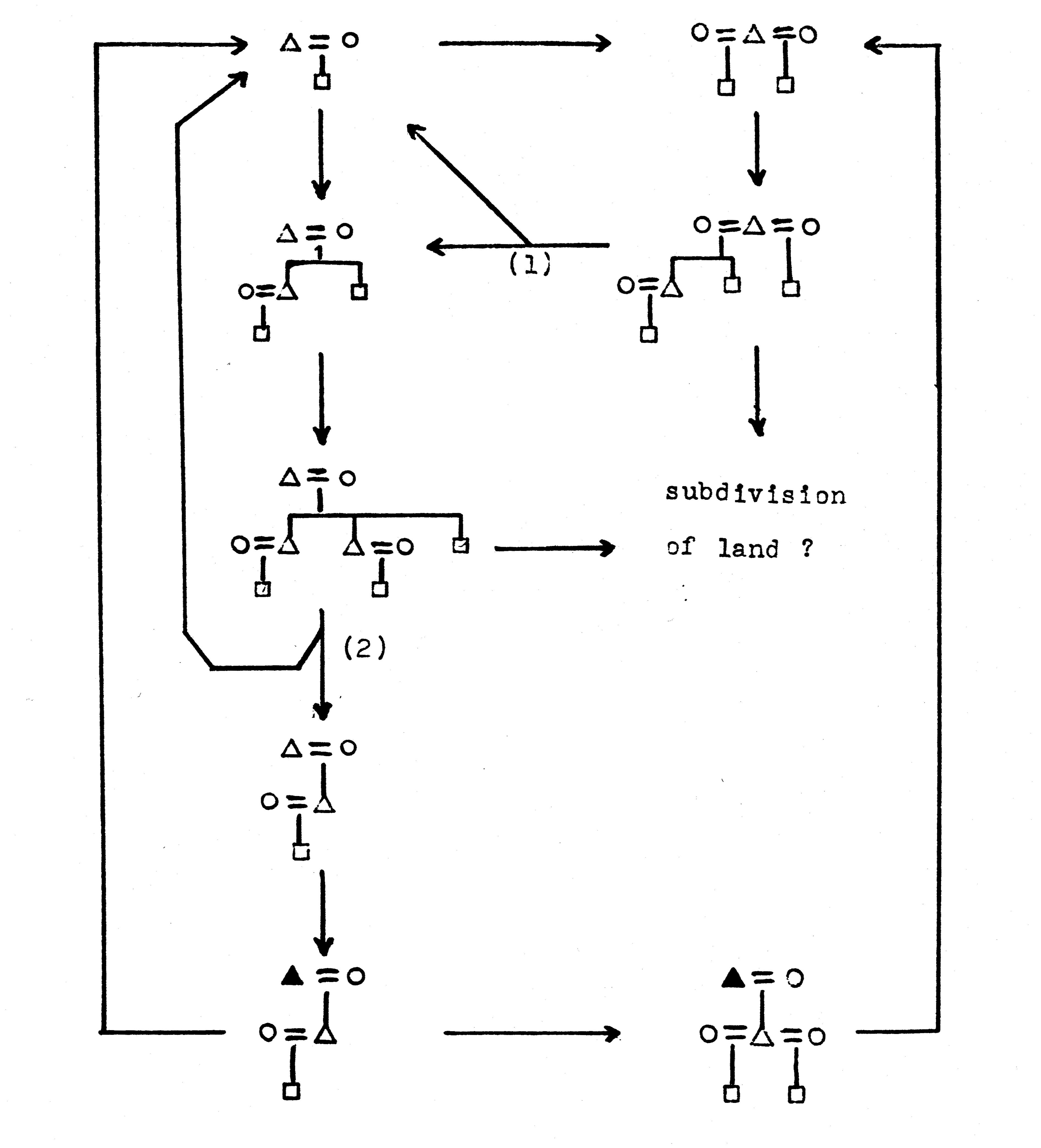

The creation of new homestead units out of the division of those of previous generations must be explained in terms of the rules of cattle inheritance. In his lifetime the typical man will pass through three stages of control over cattle: as a child and young man he is dependent upon his father for cattle and the use of their products; in middle age he acquires individual rights over some cattle while sharing rights in others with his brothers and possibly with his half-brothers; later in life he reaches the point that might be described as individual ownership tempered only by his moral obligations to his sons and descendants. Indeed, the length of a man's life, i.e., his survival in old age, is dependent among other things on how well he has maintained individual control over some of his cattle while yielding control over most of his herd to his various sons.17

For simplicity let us consider first the situation of an old man with one wife. As his sons mature and marry, the father will contribute most or all of the cattle for the bridewealth payments for their first marriages. Ideally each brother should marry in turn, and none should use any of the father's cattle for a second marriage until the youngest is married. This is not always possible, and, when departures are made from his pattern, care is taken to remember the extent to which each brother has made use of the father's cattle. One of the married sons will remain with his wife and children in his father and mother's homestead (where his wife, and their children form another household). Possibly others will stay but will hope eventually to move off to start new homesteads, either neighboring their father's or elsewhere (possibly anywhere else in Kipsigis or even in Nandi). Those sons who move away will be given some cattle with which to start their new herds (tug'ap boiyot, cattle of the elder ). Technically these cattle belong to the old man until the final division of his herd and their ultimate disposition should be approved by the father. In their daily affairs, however, these men are virtually independent, unlike the son who remains with the father.

After the father's death, but before the final division of his property, the sons should (at least according to the formal norms) still consult with each other before disposing of any animal received from the father. The actual division of the herd is not made until after the father's death, and should not take place, ideally, until all the sons have married and established their own households. Until the division is made the older brothers may have actual possession and daily use of the cattle, but hold some in trust for their younger brothers. If a son was not present during the process of dividing his father's herd, and is dissatisfied with the division made, he could claim his share upon his return, collecting a part of it from each of his brother. (As discussed below, age differences in polygynous families greatly complicate issues of inheritance.}

The cattle placed with each son to help him establish a separate homestead are technically no more the property of that son than of another. But proprietary interests naturally develop and so the de facto distribution of cattle that develops during the father's later life becomes the basis for the de jure division of cattle after his death. All inheritance calculations take account of previous use of family resources. What is left to divide after an elder's death is seen as the remainder of the family property (the wise elder retains some cattle to his direct control and does not assign all his assets to his wives' accounts). Among other things, this means that each man keeps track of the development of each of his brothers' and half-brothers' herds and the amount of family cattle spent of behalf of each (in marriages, etc.).

It is considered very bad taste, if not evidence of more malicious intent, to ask about or discuss a man's cattle in public situations. Counting another man's herd is tantamount to cursing it. Yet cattle are the major source of wealth, and although men would not discuss particular cows with me, they insisted that each man in a community could trace the life history of each head of cattle in the community, as well as recognize it by sight. As one old man put it:

Even after the formal division of the father's herd (full) brothers are under certain moral obligations to one another concerning the cattle they have inherited. At any point one of them can make a claim involving tug'ap boiyot. Settling such a claim would involve assembling the men who were originally concerned and reviewing the life history of the cow or cattle in question, and its place in the original division. Moreover, should all of the cattle in one brother's herd die, he could appeal to his brothers. In almost all cases they would each give him at least one animal. This however is considered an outright gift rather than a loan or a readjustment of the original division and is an example of a man's moral obligation toward the welfare of his brother's house (in a sense similar to assuming the duties of a leviratic marriage discussed below), rather than a binding obligation for which one could be held responsible in either traditional adjudications or current courts. Similarly, though an old man has a moral duty to look after his cattle for his sons, formally he has the power to disinherit any of them (or even the power to squander his resources).

Once an elder has reached complete agreement with his brothers over the disposition of their father's cattle (including marriage cattle discussed below), such a man is the head of an independent cattle owning family unit and is thus the sole owner of the animals which he will eventually pass on to his sons. If a man feels that his brother's cattle are not being handled properly he can only offer advice; if the division has been made he has no claim to interfere beyond that.

The division of property between brothers is final in their generation. No claim for readjustment of the original division can be made between their sons, patrilineal first cousins.18 In terms of rights to cattle, cousins are no more obligated to one another than mere clansmen, whose help is never fully binding.

The rules of inheritance result in a great number of different combinations of family units "on the ground." The variations in residential patterns combined with the variations in the timing of property division in a man's life make it impossible to judge by an application of the formal rules to any single observation (e.g., the number of people or generations represented, or the age of the eldest male) whether a particular homestead is an independent cattle owning unit, or some part of a larger unit. In each case details of the family history (and the life history of a large number of cattle) must be known if one is to understand the extent to which the people of a particular homestead form an independent unit. This indeterminate situation is positively valued among the Kipsigis, and a great deal of attention is given to keeping track of the situation among one's relatives and neighbors, and to obscuring such details from strangers.

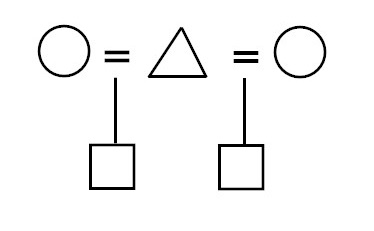

One of the most important complications of the inheritance rules described above arises in the case of polygyny. Each of a man's wives, with her children, function as an independent economic unit within the larger group, and that in matters of inheritance, the sons of one wife stand as a unit against the sons of her co-wife. In polygynous families an extra level is introduced in matters concerning the family cattle. Just as the distribution of cattle for use by the grown sons of an old man foreshadows the nature of the division of the old man's cattle after his death, in polygynous situations certain cattle are assigned to each wife for her use as her children grow up and these cattle (or their offspring) form the basis for the eventual division of property among the houses (sets of full brothers). In polygynous families the eventual division of property thus goes through two stages. First the property is divided equally by "house" (regardless of the number of sons in that house), and then within each house divided among the full brothers as it is in a monogamous family.

Thus, if the father's total estate amounted to 36 cattle, (both those previously assigned to wife's houses and cattle under his direct control), the unassigned cattle should be distributed such that each son inherits (or has already received) the number shown in this sketch:

Division of an Elder's Cattle (Tug'ap Boiyot)

The division of property by houses makes the accumulation of wealth in particular families unsustainable across generations. Table 2-3 compares the marital status of 59 men in the interview sample (discussed in detail in Part 2), with their fathers' marital status. In conjunction with the rate of polygyny shown above in Table 2-2, a number of features become clear:

- A majority of men have only one wife, yet

- a majority of women have a co-wife.

- A majority of sons have fathers who are polygynists, yet

- less than half of them will become polygynists.

- Indeed, they are no more likely than the sons of monogamists to become polygynists.

- In short, there is no relationship between fathers' and their sons' marital status (which is a direct indication of wealth in cattle).

| Fathers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monogamous | Polygynous | ||

| Sons | Monogamous | 11 | 25 |

| Polygynous | 6 | 16 |

The dominant social values clearly reflect the challenge facing men regardless of their childhood circumstances. It is recognized that sons may tend to look upon their father's wealth with envy (kibai chi, kosich kong', feed a person, get an eye ) and, in their selfishness, cause conflicts which are counter-productive for the family's resource base which ultimately made their existence possible (tet' ki i maa, the cow gave birth to a fire ). The popular caricature of a son raised in the home of a father who has achieved wealth is that of a person lacking in personal ambition and eager to fight for the spoils of his inheritance among his many competitors (ki i ng'etuny lel, a lion gave birth to a jackal ). In contrast, the qualities required to become a self-made man are highly esteemed and strength of character is considered to be forged through adversity (ma kisasunen karna maa, do not despise an iron in the [blacksmith's] fire ).

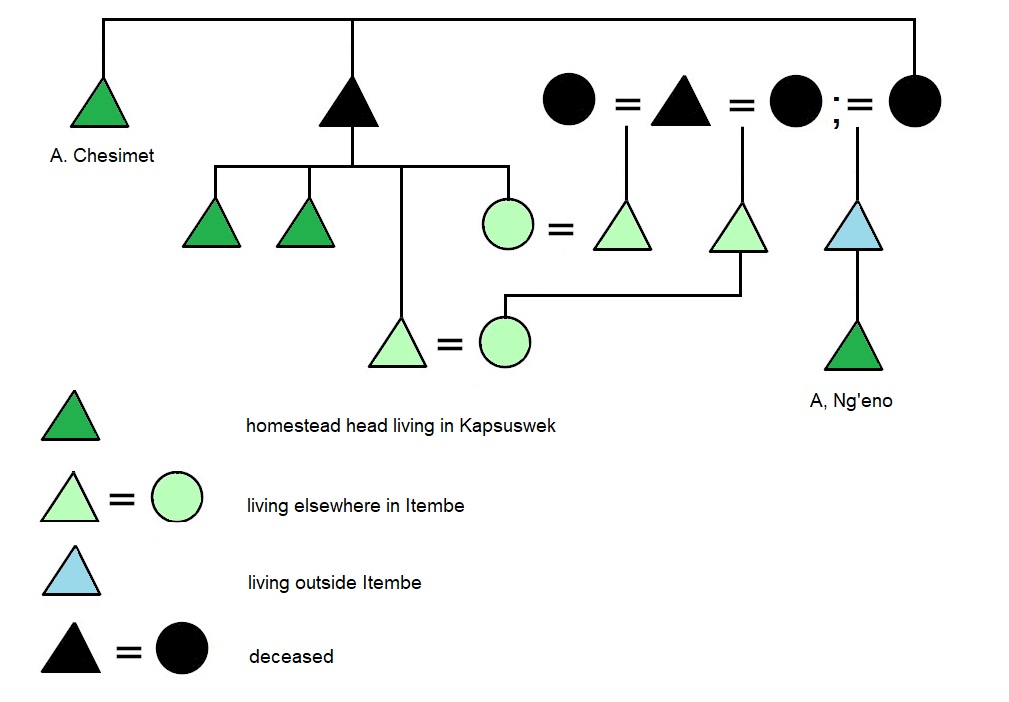

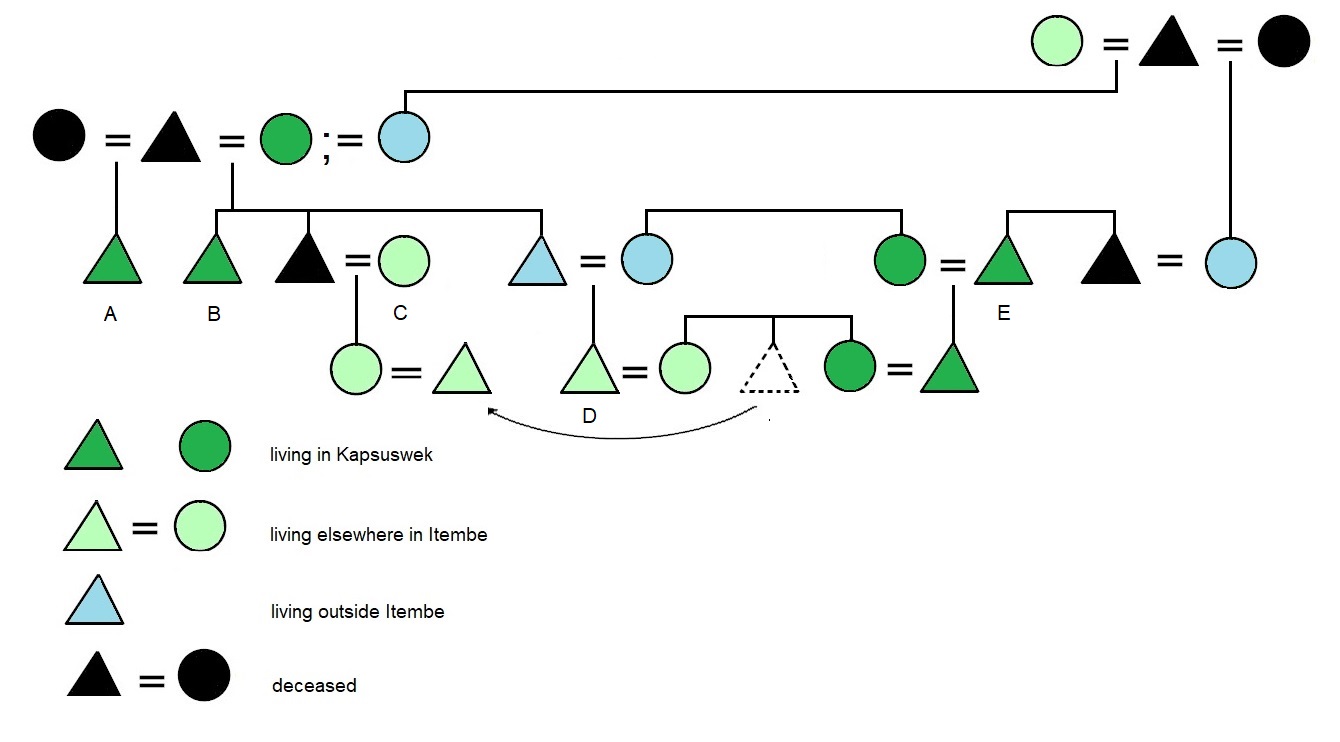

Polygyny influences family dynamics in a number of ways. First, one direct result of polygyny is that it reduces the amount of interaction between the husband and the members of one or both of his houses. This is especially true when co-wives are not co-resident. Unlike the Bantu-speaking groups in highland Kenya among whom agnatic lineages or clans share rights to land, and residence is patrilocal (on a smaller or larger scale depending upon which group is being considered), Kipsigis homesteads are individually owned and descent groups are dispersed. Prior to land enclosure all but one son in a monogamous family would leave the parental homestead upon maturity; following enclosure such dispersal was still practiced as much as possible in order to avoid subdividing plots. At least until very recently this has been possible in almost all cases through the enormous expansion of the relatively dense pattern of domestic settlement in previously open areas. While many men may initially establish their second wives on the same homestead as their first, the principle of the house-property complex leads directly to a situation of potential competition between co-wives. Thus many man find it preferable to establish different wives on independent homesteads in separate communities. This becomes increasingly imperative as sons mature and sets of half-brothers become aligned against each other. If at all possible, co-wives should be established on separate plots, each with a son who will provide for her to her old age, before their husband dies. While this may not always happen, I know of no cases of widowed co-wives who live together. Although the timing of separating co-wives varies in different families, at any one time there are a significant proportion of women with children living some miles from the usual residences of their husbands. (For a detailed discussion see my paper Residence Rules and Residence Patterns in a Kipsigis Community).

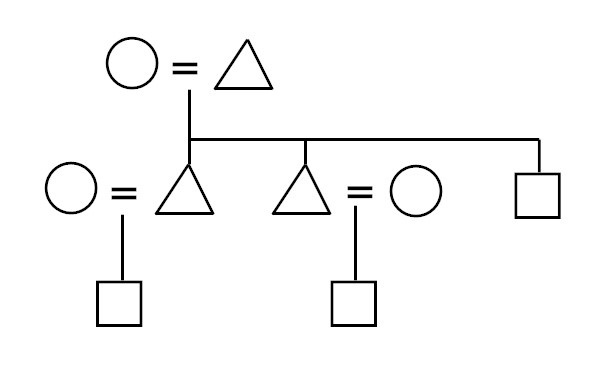

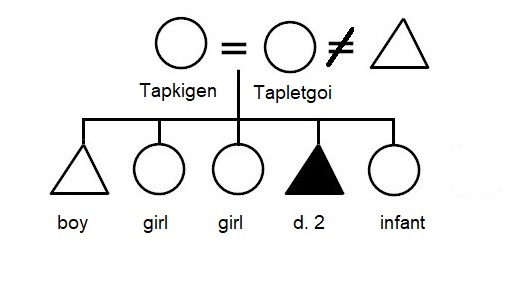

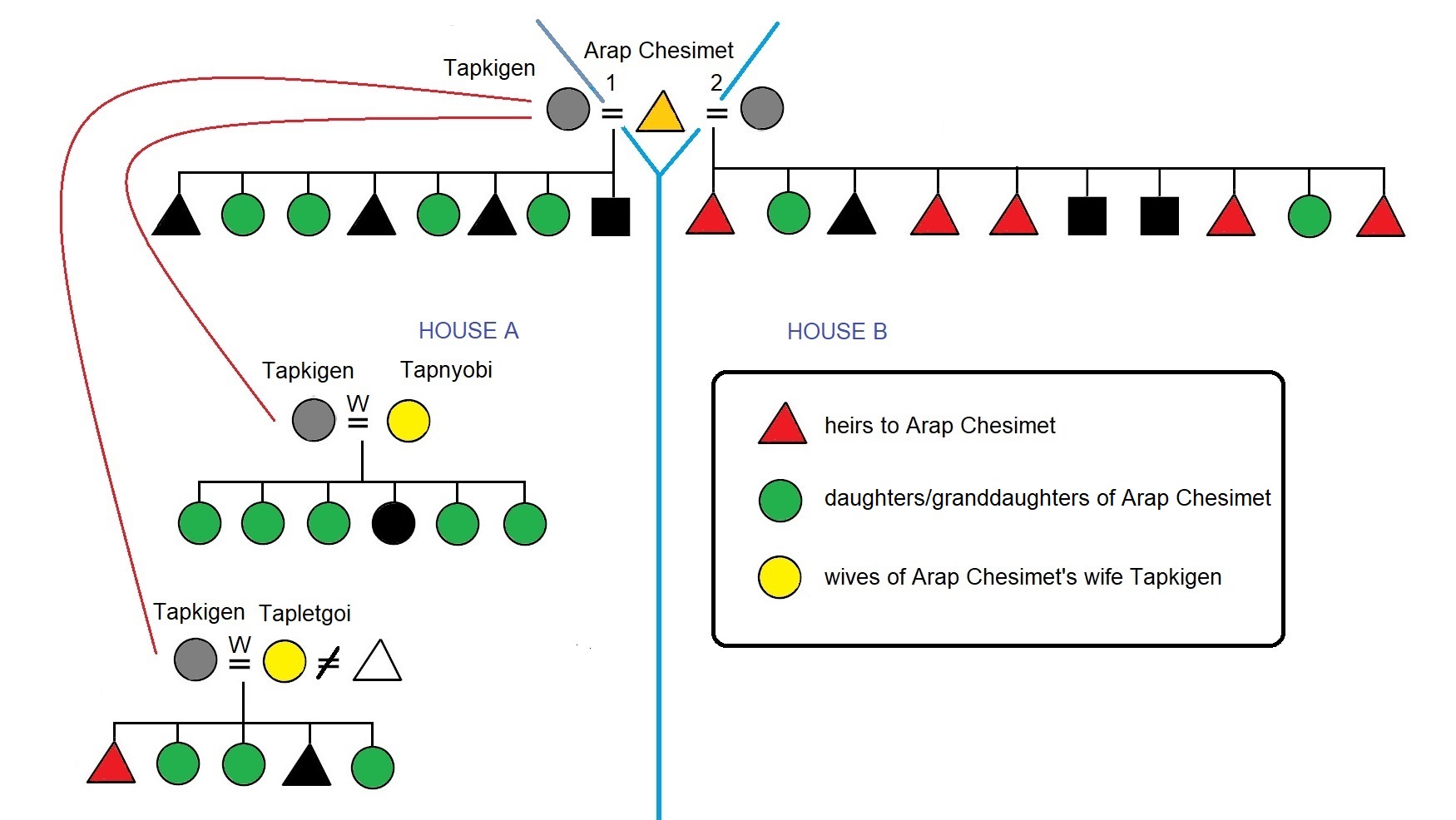

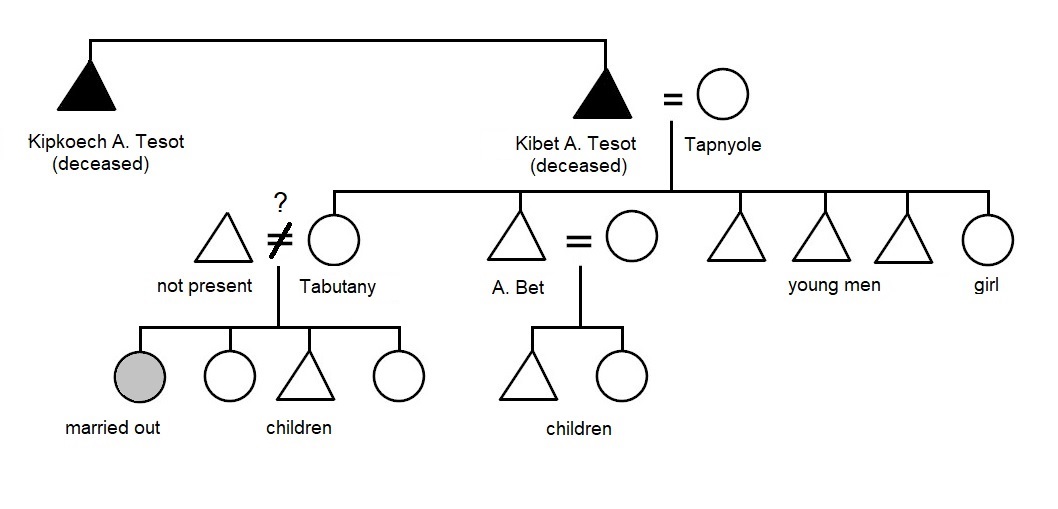

Polygyny causes great variation in the nature of the homestead group, and in the cattle sharing group (which may or may not be scattered geographically) because the great age differences that result between members of "structurally equivalent" houses. In the past all women were married at the end of their initiations. Even today all but a few are married before the age of twenty. First wives tend to be at least a few years younger than their husbands, and junior wives are younger than senior wives. It is not uncommon for co-wives to be at least a generation apart in age. In one case, among the children of a man with three wives, the first born was a grandmother while her youngest half-sister was an infant. Four quick examples illustrate the diversity of situations that can arise:

- Arap Mibei is hearing-impaired. His father arranged for him to be initiated at age thirteen and married immediately after emergence from seclusion. At age twenty he has a wife and three children, aged six years to three months.19

- Arap Kilel happened to be the only son born to one of three wives of an elder with many cattle. He also had the good fortune to have three older sisters. With a clear claim on his inheritance and the receipt of three marriage payments, he married first at age seventeen, and a second time at age twenty-one. At age 26 he felt overwhelmed by his responsibility for two young wives, one with four children, aged seven to six months, and the other with two children four and one years old.

- Arap Rotich's father had six wives. But with two brothers to share his inheritance, he struggled and finally married at age thirty-six.

- Arap Bet is an elder with a wife and eight children, the oldest a married daughter, the youngest an infant son. Now, at age 56, he has married a young teenage bride as his second wife.

Much of the conflict which arises between members of one "family" are due to such age differences taken in combination with the issue of de facto or de jure divisions of property. According to the formal rules a sixty-year-old man may still be holding cattle in trust for eventual division with his half-brothers from another house, while such a half-brothers may in fact be infants, or as yet unborn, or the male heirs in the junior house may even be one more generation removed because of a woman marriage (explained below). In practical terms such a situation is unworkable, particularly in a society in which it is quite possible that an eighteen-year-old man at the next homestead is the sole owner of cattle received from his father who dies young. The temptation is for the members of the older house to take advantage of the younger house, especially if it does not yet contain any adult sons,when parceling out the family cattle.20 Such situations also place unusual demands on women who may have to hold their position as best they can against a co-wife's sons. It thus becomes a point of contention in many Kipsigis families whether the physical distribution of animals among the various homesteads will or will not be the final, formal division of cattle to be inherited. The question of defining the boundaries of the family, if the term is taken to mean the people who share rights to inherit from one man's estate, is not merely an analytical problem but an empirical social issue faced by many, if not most, Kipsigis.

Usually bridewealth cattle include an ox or two and occasionally a young bull. The majority of the animals exchanged, however, are females, unbred heifers and cows. If a cow is accompanied by a nursing calf, the calf is not counted in the total number of animals said to be transferred. In addition most exchanges include smaller stock, ng'ororek (sheep and/or goats), and in recent years cash and perhaps some purchased trade items.

Traditionally one animal counted in the bridewealth payment has a special status. Known as the chebletiot (cheb-, female prefix + let to come last, i.e. 'the last one'). Though usually a female calf, this may be a she-goat or ewe. This animal remains with the groom's family for perhaps a few years after the marriage. When the marriage has resulted in a healthy child or two, the chebletiot is finally sent to the woman's family. For the Kipsigis one is only really married when one has children. One of the offspring born to the chebletiot during this intervening period is retained by the man's family as a manifest sign of the tie between the two families.

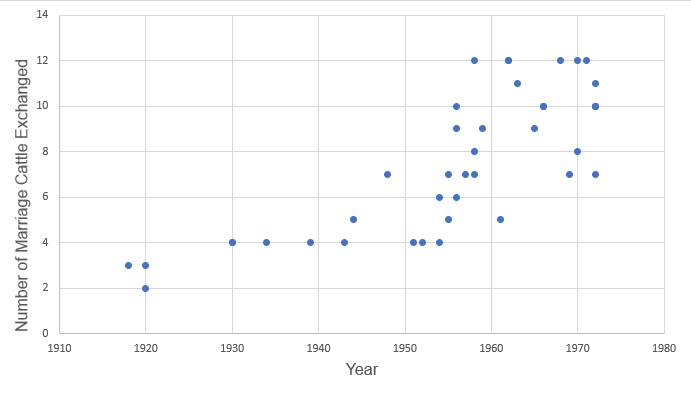

Table 2-4 lists the number of bridewealth cattle reported to have been paid in forty-one marriages involving families in Kapsuswek.21 In addition to cattle, a few to a dozen small stock (sheep and goats), were transferred in most marriages, but their numbers do not show any historial trend. The amounts of cash and trade goods were not specified in many cases and so are excluded from the table, though their value has undoubtedly increased significantly as the Kipsigis became more and more involved in the cash economy. Even without this information, however, it is clear that the value of bridewealth transfers has increased, especially between 1945 and 1960.

Number of Cattle Transferred in 41 Marriages

Involving Families in Kapsuswek Community

1918 - 1972

In a sense, each of a man's houses holds a franchise in the family business, and separate "accounts" are kept, by house, for cattle given and received in marriage. Tug'ap koito are controlled by the bride's father, if alive, but belong ultimately to the bride's full brothers. An old man can, for example, take two animals from his first homestead to give as part of the bridewealth to marry a son from his second homestead, and may even accomplish this without creating rancor between his two sets of sons, but when the division of his legacy is calculated, the sons of the first house will contend, rightly, that this expenditure of two head is to be refunded first.

Similarly, cattle received for the marriage of a daughter in one house are to be used for the benefit of that house only. Their preferred use is for her full brothers' marriages, though they can also be used legitimately for the support of her mother and siblings and, today, for such expenses as school fees for her brothers. Under no circumstances should cattle received in a daughter's marriage be used for the personal benefit of her father or half brothers in another house. Were these cattle to be used by the father for a further marriage of his own, or by the half brothers for marriages in their names, this would amount to taking the profits from one branch of the family to establish another franchise, or strengthen an existing one, which would be in competition with the first for the final division of joint property. To establish a new household on such a misuse of cattle, even if it were possible to do so by concealing the true facts from the bride's family and others, would invite inevitable disaster.

But the exact determination of each individual's identity within a particular family is critical, and the definition of paternity is therefore simple and iron-clad, or more exactly, cattle-bound. Marriage involves the transfer of cattle from the groom's family to the bride's. The person in whose name the marriage cattle are given is, by that transfer, the socially recognized father of all children born to the married woman.

Anthropologists have adopted two Latin terms to differentiate the two potentially separate aspects of fatherhood:pater refers to the socially recognized father, the person whose marriage to a child's mother bestows legitimacy on that child. Genitor refers to the physiological sire of the child.

Ethnographies from the colonial era often translated indigenous terms for cattle or other property exchanged in African marriages, e.g.tug'ap koito, as brideweath or "brideprice." Bridewealth should not be confused with its opposite, dowry, which is propertry the bride's family brings to the husband at marriage. "Brideprice" is more problematic since to the modern mind it suggests women are somehow the subjects of commercial purchases. The confusion is two-fold. There are, at times, market considerations in setting the amount of property involved.22 The deeper issue lies in translation. In Kalenjin the verbs ke-al and ke-alda, which long antedate any formal currency, mean to receive in an exchange and to give in an exchange (-ta/-da is a suffix indicating movement away from the speaker). These words are now used, quite naturally, to mean "to buy" and "to sell." But wives are not bought or sold. What is exchanged for the tug'ap koito is, in technical terms, rights of filiation (from Latin filius, son, filia, daughter), that is the husband's right to claim the bride's children as (his) sons and daughters for all matters of inheritance and future marriage, thus establishing the primancy of patrilineal descent. It is this particular sense of paternity that is transferred to the bridegroom's family by marriage.

In America a determination of "paternity" [as in the courts] is a search to identify the genitor, in East African pastoral societies "paternity" is concerned with determining the socially defined father, the pater, the person from whom the child derives his or her identity in the family and thus in wider society. If thepater and the genitor are two different people, our courts expect that in general biological events should be used to define legal and financial obligations, while the Kipsigis (who after all breed animals and have no illusions about reproductive behavior) hold that kinship is fundamentally social and moral.

It is expected that in a usual marriage a man will enjoy exclusive access to his wife's sexuality, and thus will be the genitor as well as the pater of all her children. It is also well understood that this is not always the case. Most obviously a discrepancy can arise in situations of adultery. As disruptive as such events may be to personal relationships, legally it does not matter whether the husband suspects his wife has "found a baby in the bush" (rather than in his bed) or whether she has left him and lived openly with another man for years. Non-coresident polygyny provides many opportunities for adultery, of course, and no doubt in some extreme cases involving very old men who have married six or seven wives as a means of reinvesting cattle, it is quietly accepted.23

I know of a few instances in which a marriage was annulled and the young woman subsequently remarried, and successfully bore children. In a few other cases a woman with children has returned, or been returned, to her natal home, but her husband was unable to recover his cattle (a father should not shelter both his married daughter and the cattle given for her marriage).

As long as the marriage remains formally in force, the husband is the socially recognized father of all children born to the wife. The alternative, divorce, involves the return of the marriage cattle (including, in theory, any calves born to the cows since the exchange) to the husband. It logically follows, therefore, that a husband who accepts back marriage cattle thereby surrenders claims to paternity over all (past, present, and future) children of the wife being divorced. The critical moment in a traditional divorce ceremony comes when the man and woman anoint each other (ki-ilge). As with other moments of anointment, for example at the start of initiations, this marks a change their social status. They then address each other by their childhood names (e.g. 'Kiplang'at', 'Chebkemoi') thus ending their observance of respect for each other.

However, once a couple has a child, the difficulties involved are such that divorce is resorted to only in rare and exceptional circumstances. It also follows that once a son has been initiated, his mother cannot be divorced. Having been given an adult patronym, Arap X, the son of X, his inheritance or even his life may be taken from him but his paternity cannot be denied.

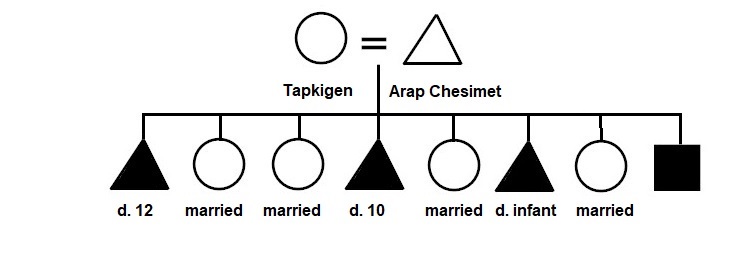

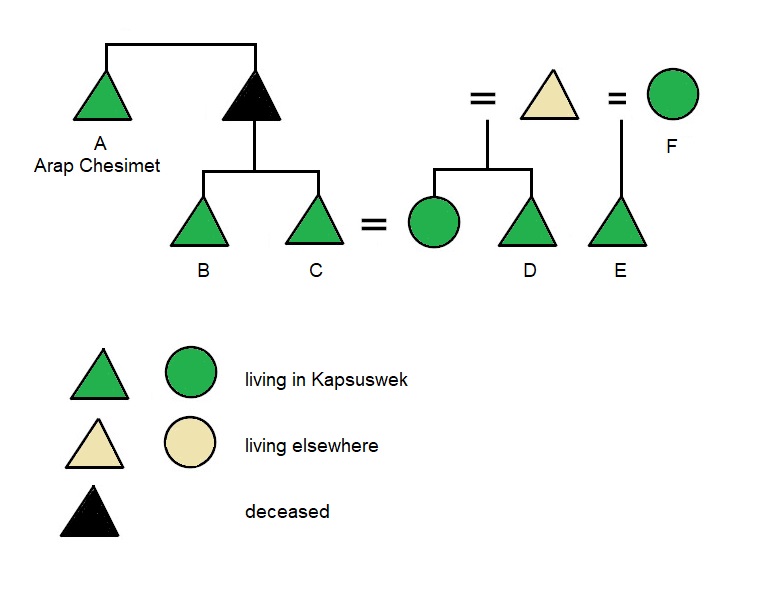

I know of only one case in which a woman with children was formally divorced and remarried (the case of Arap Chesimet, discussed below). Apparently it is nearly impossible for a husband to recover marriage cattle from his wife's family long after the marriage unless they in turn acquire cattle to compensate him by accepting a second marriage transfer from another party. As Orchardson comments (1961:79): "The object of divorce is to allow the woman to marry again." Thus (at least prior to urban life) there were no single divorcées.24

If one considers marriage to be a relationship between a man and a woman, then the determination of paternity by cattle transfers rather than the events of human physiology may seem rather arbitrary, adding an unnecessary rigidity to the terms within which inevitable interpersonal problems must be handled. And undoubtedly there are Kipsigis who feel at time that the rules of their culture are maladaptive for the individual. Marriage among the Kipsigis, however, is not a contract between two persons but between two families. The definition of paternity is a reflection of the essential requirement of the system to preserve a continuous and unambiguous pattern of associations between families and herds. This can be seen more clearly when one considers the question of paternity in the context of two other basic principles of marriage in traditional Kipsigis society. First, everyone should get married. No other role choices were available.25 On this there is universal agreement among my informants (and earlier accounts). Even in cases of abject poverty, marriages were achieved by elopement or the promise of some future transfer of bridewealth. In all my genealogical records there is only one case of an adult who remained unmarried, a man described as severely retarded. The deaf and dumb, the blind, the crippled, if they survive childhood, marry.26 Second, no healthy woman should be denied a normal career of motherhood.27

Once married, a woman is assured of the legitimacy of all her children. Children, especially sons, increasingly validate her place in society and contribute in her later years to her moral and physical support. Should a man be unable to make his wife pregnant, it is his responsibility to arrange, or at least condone, a relationship that will produce children. Refusal to do so would amount to discarding the wife's future (as well as his own), and is one of the clearest grounds for divorce that women have.

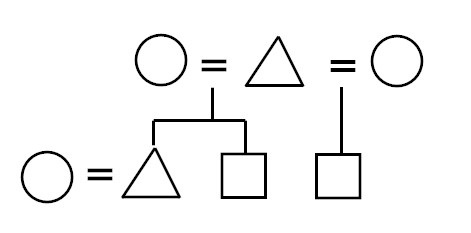

Secondly, the competitive nature of polygyny reinforces the value that each marriage should result in a separate "house" with one or more sons who will eventually inherit a part of their father's cattle. This in turn can lead to particular marriage practices which, if successful, result in creating male heirs in the house in question.

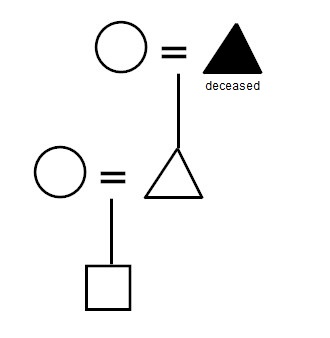

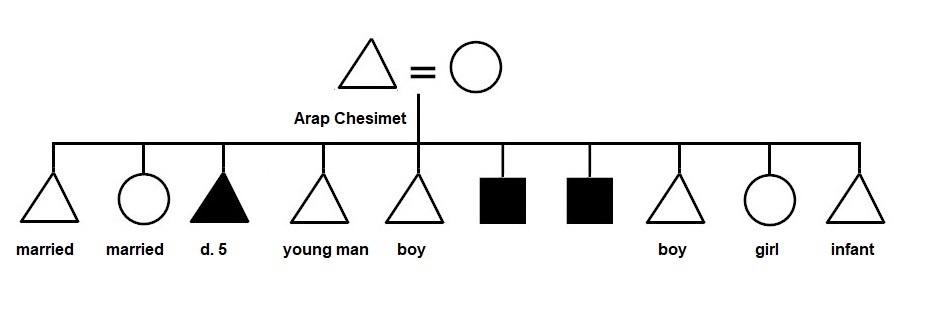

In keeping with the understanding that marriage is not a relationship between two individuals but is a connection established between two families, marriages continue after the death of the husband's death. In anthropology the levirate or leviratic marriage usually refers to situtations in which a widow marries her dead husband's brother. But as the Kipsigis handle this situation, when a married man dies, his wife does not remarry; her marriage to her original husband continues until her death. The deceased's brother or other suitable close agnate (who must be of the same age-set as the deceased) becomes responsible for continuing to husband the widow and her household on behalf of the deceased. The husband-surrogate is known as the kipkondit (kip-, the male prefix + kondo, eye, hence `male supervisor'). Since the original marriage remains in force, if the widow is young she may bear further children by this man. They are the sons and daughters of the deceased husband. Thus one's pater could have died years before one's birth. (Hence the practice, mentioned earlier) of having ailing boys initiated and married early.)

A man assumes the role of kipkondit in addition to his own marriage or marriages; this responsibility in no way diminishes his desire to marry on his own behalf nor his claims on family cattle to do so. The extent to which the kipkondit interacts with the widow and her children on a day to day basis varies according to such considerations as her age, and hence the extent to which she conducts her personal life independently of her husband's family, and her proximity to the kipkondit's residence. However such details are handled, the formal definitions of marriage and paternity guarantee the rights of all concerned, including the unborn, to their proper share of the family resources.

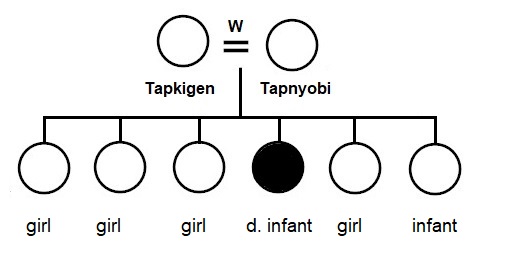

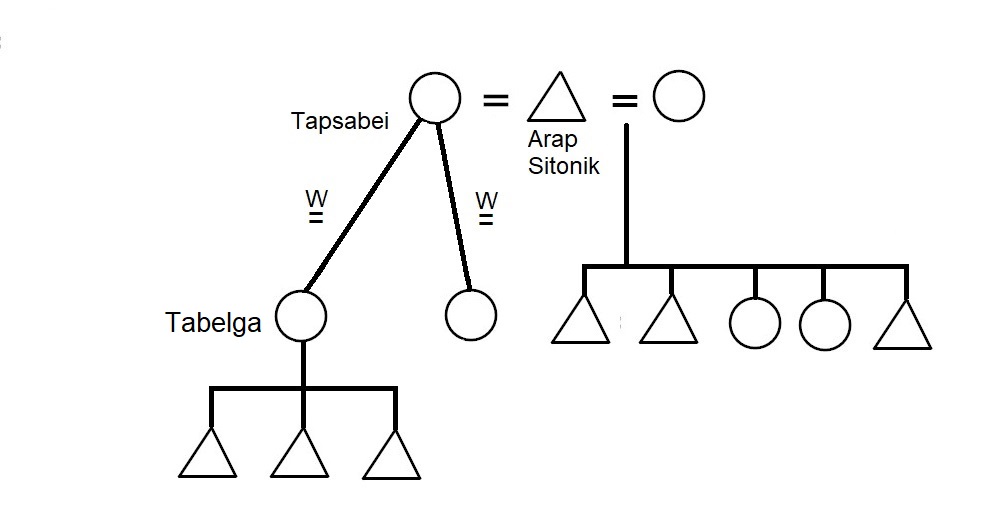

In Kalenjin this arrangement is called kotunji toloch which literally translates as to marry ko-tun someone -ji, or -chi [as a] house post toloch - the center post supporting the main rafter beam inside a house ('someone' here implies a bride; in the Kalenjin language, men marry women, women are married by men). the phrase kotunji toloch is a metaphor for shoring up a "house" in danger of collapse, in this case not architectural but social collapse. This practice was unfortunately labeled "woman marriage" in the colonial literature, and I have used that term here with reluctance. A far better term in English, I suggest, would be "daughter-in-law marriage."

While the terms for husband and wife, or bridegroom and bride, are useful for explaining the roles of the old woman and the young woman, these terms are not used in daily speech. Technically the children's pater is the old woman in her role as the old man's proxy. But unless one inquires specifically about the situation, it is not evident from daily behavior or the use of kin terms that the relationship between the two women is technically that of husband and wife rather than that between an old woman and her widowed daughter-in-law. The young woman refers to the old woman and the old man as her mother-in-law and father-in-law (she addresses them as the familiar term for mother, and the formal term for father, as any daughter-in-law would). The young children call the old people grandmother and grandfather (viz Peristiany l939:8l-83; Orchardson l96l:78). A casual visitor, coming to a homestead in which a grandmother lived in one house and her daughter-in-law lived in another just yards away, with children running about, would not know by anyone's behavior whether the younger woman's husband was momentarily off at the shops, or a migrant laborer, or deceased, or never actually existed.

The practice of kotunji toloch was still common during my research in the 1960s. There is no difference from a more regular marriage in the amount of marriage cattle exchanged. There seems to be no shortage of brides willing to be involved, indeed I suspect some prefer the partial freedom of being an 'instant widow' with a part-time supervisor over an arranged marriage to a full-time husband. In the short run the arrangement provides a daughter-in-law who will hopefully see to the old woman's care in her old age. But this is not a way to care for old widows. Most significantly, in every case for which I had information, kotunji toloch marriages occurred in families in which the elder was still alive, and had at least one other wife who had adult sons. For the elder, there is the compelling motivation of continuation of a branch of the 'family business.'

Kipsigis social principles are the products of an evolved (and for the most still very real) dependence upon cattle. Formal relationships of descent and affinity are shaped by the fact that they carry heavy implications about family herds. Priority is necessarily placed on norms which favor the support of existing units of ownership and a viable distribution of resources among them. Issues such as paternity are contractually defined because they are too vital to leave to the errors or misfortunes of individual lives. Through marriages households are established which identify certain people with certain resources. As the practice of the 'leviratic' extension of marriages shows, once such an investment has been made there is every reason to promote its continuation. Indeed the usual definitions of gender and descent can be formally manipulated, when necessary, through "woman marriage" and "daughter adoption", to maintain family lines. The demand that each house contains at least one male heir thus produces situations in which one's father (pater ) can be a young adolescent, a sterile or impotent man, a very elderly man, a man long dead, one's grandmother, or one's mother.

In principle the rules concerning the distribution of inherited cattle and marriage cattle are easily stated. In practice, as these rules are applied in particular families with differing numbers of sons and daughters, they generate patterns whose complexity quickly goes beyond the available data. Nonetheless the major implications of these rules for the flow of property in Kipsigis society can at least be suggested.

To begin with, the number of cattle a man acquires which are primarily intended for his use as bridewealth is a function of the number of his full sisters (the number of marriage payments received by his house) compared to the number of his full brothers (the number of men with whom these cattle must be shared). It follows that men with more sisters than brothers are more likely to have the cattle necessary for second marriages (because the cattle involved in a marriage exchange amount to a significant proportion of a typical family's wealth: roughly a third of the number of animals on the average homestead in the more pastoral zone). Among the 58 men in my interview sample (discussed in detail in Chapter 7), 26 had more sisters than brothers, and of these men 14 (54%) were polygynists. Among the 32 other men with as many or more brothers than sisters, only 9 (28%) were polygynists.

The accidents of birth within sibling groups play a major part in determining who accumulates cattle. Early in my fieldwork I attended a beer party given by a very old man who had started life with little and through warfare, trading, and shrewd management ended up with many cattle, three wives, and several sons. Another elder at the party, a rather cranky, humorless character had a daughter married to one of the host's sons. This elder was thus accustomed to being given the place of honor in this house. During the colonial era he had some bad experiences at the hands of the British, and was convinced I was up to no good. He attempted to dominate the discussion, demanding that I explain my presence. Although I was quite willing to do so, my host took offense, instructed me to remain quiet, and told the other elder that he was overstepping his rights as a guest. After repeating the demand and being rebuffed by the host two more times, the other elder stormed out of the party in a huff, and the host turned to me and said "Don't pay any attention to him; he thinks he's a big man but he simply had a lot of sisters."

However a man acquires cattle, when their number exceeds a certain level he is likely to take another wife, reinvesting cattle in further dependents (although few men achieve the sustained success necessary for three or more marriages). Moreover, different men undoubtedly recognize different thresholds at which they choose to expend another bridewealth payment and start capitalizing another house. This introduces still more variance into the amounts of sons' inheritance. Thus the sons of a rich man are not likely to start their own careers with any particular advantage. The amount of cattle a man receives from his family of origin depends, for tug'ap boiyot, upon his father's wealth, the number of his father's wives, the timing of his father's marriages, and the number of his full brothers, and for tug'ap koito, upon the ratio of sons to daughters in his mother's house. To these basically unrelated variables must be added, of course, the many vagaries of animal husbandry itself.

In the aggregate, each generation benefits from the pastoral accomplishments of the previous generation. But traditional relationships between cattle and individual lines of ownership have sharply different implications for the two sexes. From the point of view of dependents, women and children, the requirements of raising a significant amount of bridewealth and initial capital to establish a new house means that brides are sent to those families which demonstrable have the extra resources to support them. Since marriage was universal (and in this comminity still expected of everyone), it is true that some women are necessarily married as the sole wives of men with few resources. But not all monogamists are poor (quite aside from those who are monogamists for modern reasons). It is highly unlikely that a man would contract a second marriage without adequate resources for both houses. When these considerations are combined with a high rate of polygyny, it is clear that in the vast majority of cases, people were, at last before the cash economy penetrated deeply into their lives, being matched with resources. The effect of bridewealth, polygyny, and the various rules comprising the "house-property complex" maximize the benefits derived from family herds by allotting rights to use their products far more equitably among women and children than the fluctuating patterns of their formal ownership among men. For men, however, these practices continually lead to random inequalities. Differences in acquired wealth mean that there will always be some willing to take large risks to acquire cattle from outside the society, while the instability of wealth in patrilines means that a high degree of interdependence has to be reestablished in each generation.

The third major system of rights to cattle is called kimanagan, or cattle given on loan. The loan arrangements are not directly related to family composition. Briefly, a cattle loan gives the recipient rights to the products of the cow (and any calves born to her) in return for her care and feeding. Although a man may on occasion send a wife or child to a man to whom he has lent cattle to collect milk from those animals (if, for example, he will be hosting a large gathering for an initiation or marriage), he cannot ask for their return on short notice or in an abrupt manner.

Loans are not made between patrilineal cognates or affines since these relationships already involve rights to cattle that may interfere with a loan arrangement.

Kimanagan loans function to redistribute cattle more evenly among different homesteads and different areas. By spreading his assets in different areas, the lender (komonoktoindet) insures against the loss of all his cattle by any local catastrophe (drought, disease, enemy raids, seizure for murder compensations, or whatever). He also gains some secrecy in the management of his estate, which can be usefully played against his wife's or wives' attempts to gain de facto control of cattle attached to a particular "house."

The recipient of an animal is expected to care for her responsibly, but is not blamed if the animal dies for reasons other than might arise through negligence. He is bound to report the death of the animal to its owner, usually by sending him the hide (for positive identification). When a man dies, all those who hold his cattle in kimanagan are morally bound to report the exact status of the loan to the deceased man's chosen son (even if the son is ignorant of the extent of his father's loans). All of the old men who discussed kimanagan arrangements with me were adamant in stating that any attempt to conceal such matters from the rightful owner or heirs of the cattle would result in divine retribution being visited upon the dishonest man's family. They could all cite cases they had known to support their view.

Before an elder dies he is expected to inform his favorite son (most certainly the one who lives with him) of the details of every kimanagan arrangement in which he is involved, both as a lender and as recipient. The favorite son is thus, in a partial sense, the executor of his father's estate until the time of the final division of property among the heirs. Knowledge of kimanagan assets and debts is a sacred trust that must not be used to take advantage of the other heirs.

While this system of cattle loans serves to integrate Kipsigis society, it greatly complicates the discussion of family and homestead economics. Although it is doubtful if any man ever has as many as half of his cattle out on loan, it is extremely unlikely that the herd of cattle on any one man's homestead (even that of an independent elder) are all his cattle and only his cattle. Throughout the above discussion of cattle ownership and family organization, where the term "herd" has been used, this should be taken to mean the total assets of the head of the household, and not the herd in the sense of the animals that are physically herded together at the homestead.

Distinct from any consideration of inheritance as discussed above, a son may receive one of his father's cattle as a reward or as a sign of approval for some accomplishment. The father would probably select the animal from his personal herd, though he could, at the risk of provoking friction, take any animal which he had assigned to another son. The other sons have no rights whatsoever over the gift animal, and it is not counted as one of the tug'ap boiyot to be divided among the heirs after the father's death (there is no special term for an animal given to a son in this way).

Another type of gift occurs when a son or daughter leaves initiation seclusion. It is customary for the father to present the initiate with an animal to show his pleasure. A young bull or steer is the usual form of the gift, and is called tet'ap korokto, the cow of the walking stick, because of the association of the gift with a walking stick cut from a branch which the initiate carries when leaving seclusion. These animals become the personal property of the recipients. For daughters emerging from seclusion the gift is usually a female calf. A female calf, sheep, or goat is usually given to the woman who performed a daughter's initation as well. These are the only instances of outright cattle ownership by women (some women acquire caretaker rights to cattle if they have no husband, as in cases of women marriage or "daughter adoption”). Even in the case of a gift to a daughter (soon to be married), if the woman's husband proves to be a domineering person (which is something of the Kipsigis male ideal), he may assume complete control of the animal. In some instances may even slaughter it for his own purposes (which the Kipsigis logically consider the ultimate right of ownership).

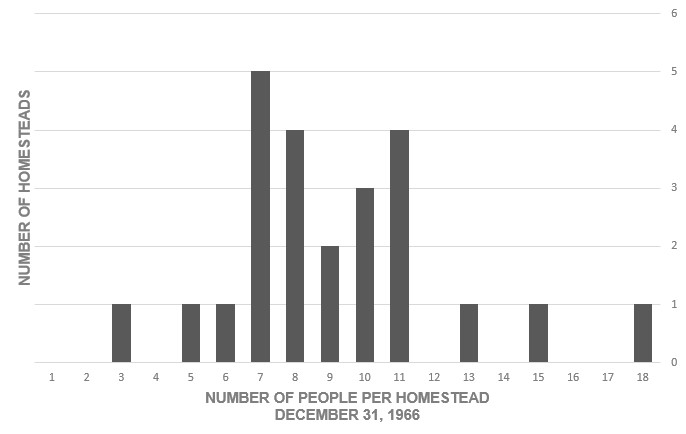

| December 31, 1966 | June 30, 1972 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Living at Home | Full Time | 211 | 236 |

| Part Time | 3 | 8 | |

| Absent | Migratory Workers | 1 | 12 |

| Dependents of Workers | 0 | 4 | |

| For Personal Reasons | 3 | 4 | |

| Children Visiting Relatives | 1 | 1 | |

| Totals | 219 | 265 |

Changes in the Population of Kapsuswek

Between December 21, 1966 and June 30, 1972

| Increases | Decreases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Births | 63 | Deaths | 7 |

| Brides, married in | 5 | Brides, married out | 7 |

| Immigrants | 5 | Emigrants | 13 |

| Subtotal | 73 | Subtotal | 27 |

| Total net incease | 46 |

| December 31, 1966 | June 30, 1972 |

|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married Adults* | 32 | 47 | 37 | 57 |

| Young Unmarried Adults |

13 | 0 | 16 | 2 |

| Uninitiated Children | 72 | 55 | 82 | 71 |

| Subtotals | 117 | 102 | 135 | 130 |

| Totals | 219 | 265 |

The most striking feature in these comparisons of census data is clearly the high rate of natural population increase. In addition, these data suggest in several ways the increasing involvement of community members in economic change which are widespread in Kenya.

In 1966, two of the part-time residents were men who regularly divided their time between their families in the community and second wives in distant communities (a middle aged man who spent the majority of his time in Kapsuswek because of local employment with the government, and an elder who stayed in the community for short periods every few months in order to remain active in events involving his relationships with several of his neighbors). The third part-time resident was a very atypical old woman who came and went at seemingly random intervals (see the description of Arap Tesot's household, below). By the middle of 1973, five others were spending large amounts of time outside the community: two men, both monogamists, who were developing farms elsewhere, another who was spending the work week running a shop a few miles away, and two young unmarried women attending schools outside the community.

Although almost all the older men in the community had spent part of their early adult lives in migrant wage labor, only one member of the community was working outside the district in 1966 (serving in a branch of the security forces stationed in Nairobi). Several other young men, living at home, were engaged in casual labor locally. By 1972 the man in Nairobi had moved his wife and three children to the city, clearly a temporary arrangement made possible by a relatively high salary, government housing, and job security. The eleven other men absent in wage labor represent the more usual pattern of individual workers trying to raise money to finance their first marriages back in the home area (three men), or to support a young family that remains home (eight men, four with young children). Eight of these men were working on the tea plantation in the northern part of Kericho District. The three others were in Nairobi.

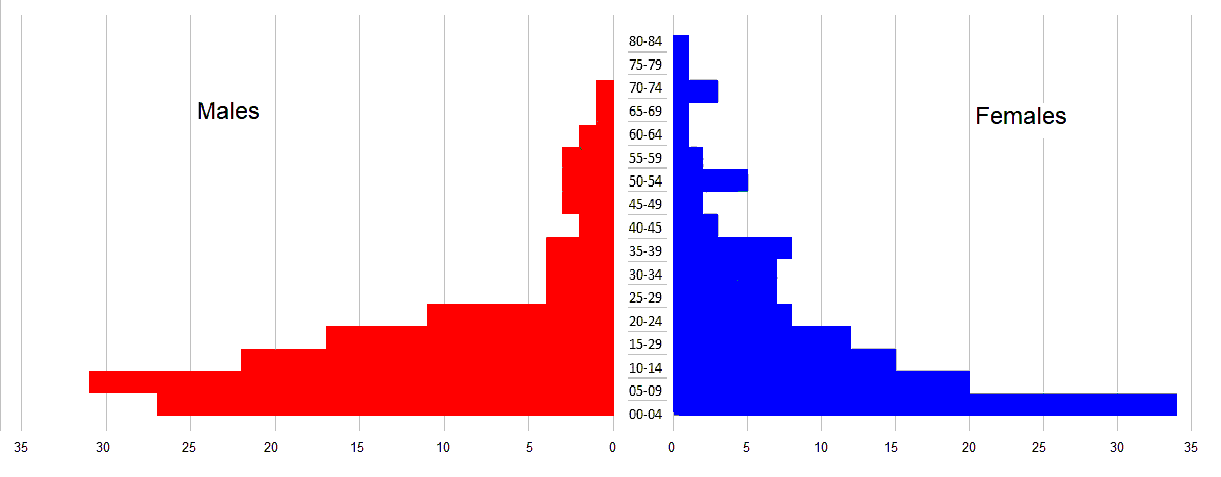

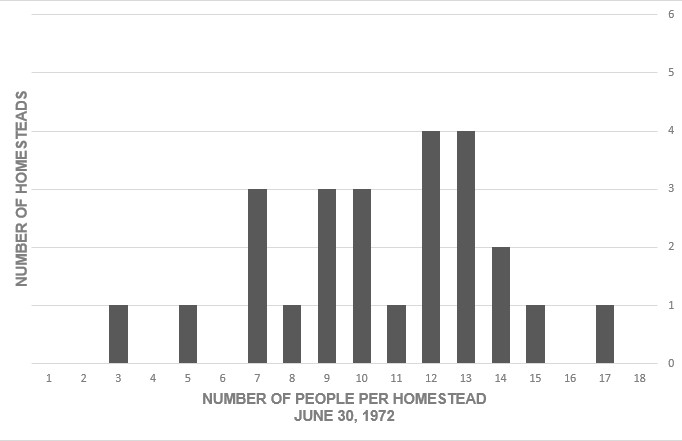

Age-Sex Pyramid, Kapsuswek Community

June 30, 1972

While one community is much too small a sample to allow accurate estimates of overall demographic patterns, the age-sex pyramid of Kapsuswek suggests the high birth rate that characterizes the Kipsigis, and indeed the highland populations of Kenya as a whole. The median age in Kapsuswek in 1972 was an astonishingly low 13 years. During the five and a half years between census dates, 33 women in the community gave birth to 65 children, 27 boys (all of whom were surviving in June, 1972), 37 girls (two of whom died in early infancy and one child who died of accidental injuries at approximately one and a half), and one child who died in infancy for whom no further details were reported. In addition to these four infant deaths, two men, aged 65 and 69, and one boy, age ll, died during the interval between censuses.

| Males | Females | ||||||