THE SETTING

The Kipsigis are the largest of a cluster of closely related groups in Kenya speaking various dialects of a language now known as Kalenjin.1 In the earlier literature this language has been generally referred to as Nandi (Huntingford 1953, Greenberg 1963) or Nandi-Kipsigis (Tucker and Bryan 1964).

The main subdivisions of the Kalenjin speakers, and their populations according to the 1969 census (Kenya Government 1971:15) are given in Table 1.

| Kipsigis | 471,459 |

| Nandi | 261,969 |

| Tugen | 130,249 |

| Keyo | 110,908 |

| Marakwet | 79,713 |

| Sabaot (Kony, Pok) | 42,268 |

Table 2, based on the 1962 census (Kenya Government 1964), gives the percentage of these groups then living in their respective home districts, and the extent to which each group was represented in the total population of their district.

| Group | Home District | Percent of Group in Home District | Percent of Total Population of Home District |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kipsigis | Kericho | 84 | 74 |

| Nandi (Including Terik) | Nandi | 63 | 90 |

| Tugen | Baringo | 94 | 79 |

| Keyo Marakwet |

Elgeyo-Marakwet | 90 97 |

97 |

| Sabaot | Elgon Nyanza | 81 | 6.5 |

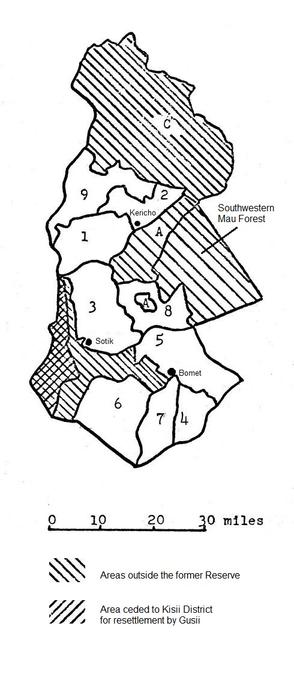

Figure 1-1 indicates the counties which comprise the home area of the Kipsigis.2

Map 1

Location of Kericho and Bomet Counties (Formerly Kericho District) in Kenya

adapted from https://dreamcitieskenya.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/map.png

The Kalenjin cluster is related linguistically to the Pokot (Pakot, "Suk") group to the north and to the Tatog group (Barabaig, etc.) to the south in Tanzania. Tatog and Kalenjin languages are not mutually intelligible; Pokot is not totally intelligible to speakers of some of the more distant Kalenjin dialects although the Pokot-Marakwet border shows certain continuities. In contrast to the linguists' classifications, the term Kalenjin is used by speakers of these dialects to include the Pokot. There is, however, no term in the language for the wider Pokot-Kalenjin-Tatog linguistic grouping and most Kipsigis have little awareness of the Tatog speakers in Tanzania. Huntingford (1953) refers to the Pokot, "Nandi" (i.e. Kalenjin), and Tatog group collectively as the Nandi Group (which he combines with the Masai [Maasai] Group on the basis of geography and calls the Southern Nilo-Hamites). Tucker and Bryan (1964) use the term Kalenjin for the P-N-T group (thus using Kalenjin in a wider sense than is done by the Kalenjin speakers themselves), and classify it as one of the groups of the Paranilotic languages along with Maasai, Teso-Karamojong-Turkana, Lotuho, and Bari. Greenberg (1963) refers to the P-N-T grouping as Southern Nilotic, and to the others as Eastern Nilotic in contrast with the Western Nilotic. Although the term Nilo-Hamitic has been strongly debated and is no longer used by linguists because of its association with discredited theories of Hamitic influence3, it was still being used at the time of my research in governmental and popular publications in Kenya where it served to label a series of groups sharing a general cultural background and to some extent common political and economic positions in modern Kenya distinct from those of the Bantu-speaking groups and the Nilotic-speaking Luo.

The Kipsigis dialect is most closely related to the speech of small hunting communities of Okiek in the adjacent Mau forest and to the dialect of the Nandi, the second largest Kalenjin group and the only other Kalenjin speakers among their immediate neighbors. The Nandi and the Kipsigis have always shared a high degree of interaction. The differences between Kipsigis and Nandi dialects are minor and offer no problems for complete mutual intelligibility. Within Kipsigis differences in local speech patterns are extremely slight and socially insignificant.

The Kipsigis refer to themselves as Kipsigisiek (singular Kipsigisindet).4 These are the definite, secondary, or exclusive forms of the nouns. The corresponding indefinite, primary, or inclusive forms are Kipsigis and Kipsigisin. The etymology of Kipsigis cannot be definitely established though it has been conjectured that it is derived from sigisiet, birth (Orchardson 1961:1). Kipsigis can be used to refer to the people, the land, or the language in place of fuller phrasing bik ap Kipsigis, the Kipsigis people; emet ap Kipsigis, Kipsigisland; ng'alek ap Kipsigis, the Kipsigis language ). While these terms are generally used to refer to all members of the society, they start with the male prefix, kip-. Gender can be emphasized by using the contrasting feminine forms, Chepsigisiek, Chepsigisindet, etc.

During the earlier years of the colonial period the administration referred to the Kipsigis by the misnomer Lumbwa. This term is derived from the Maasai I-Lumpua which denoted the Kipsigis and several other settled groups, including Maasai speakers, who practiced agriculture (Huntingford 1953:11). Lumbwa has survived as the name of a railway station and trading center in the northeastern part of Kericho District but has long been dropped from official usage when referring to the Kipsigis people.5

Traditionally the Kipsigis recognized three main divisions of their homeland, delineated by rivers flowing down from the highlands to the east. The northern section is Belgut where the town of Kericho, the county seat, is located; Bureti is in the middle; and Sot in the south. These areas have become formalized into three administrative divisions, Belgut, Bureti, and Bomet (from boma, Swahili for "kraal" or "compound").

In addition to these three parts of what became the Kipsigis Reserve in the colonial period, the present boundaries of the district include a large area south and east of Kericho township owned by British-affiliated tea companies, an area in the southwestern part of the district formerly occupied by European farmers (East, West, and North Sotik) now consisting of resettlement schemes started in the mid-1960s and a few small tea estates, and a much larger area northeast of Kericho that was formerly all alienated land but in the years following independence was mixed resettlement schemes and European farms. The district also includes a section of the Mau Forest east of Bureti.

The senior administrative official in the district is the District Commissioner. With him in Kericho are his assistant, the First District Officer (DO 1), the District Officer in charge of Belgut and Bureti Divisions (DO Belgut/Bureti), and the District Officer in charge of the area northeast of Kericho town (DO Settled Areas). The fourth District Officer (DO Bomet) is stationed in Bomet (formerly called Sotik Post) 28 miles to the south (approximately 45 miles by road). In Kericho the various branches of the national administration are represented by officers from the Departments of Labour, Agriculture, Veterinary, and Community Development. Assistant Officers from these last three departments are stationed in Bomet. It is general policy that officers serve in posts outside their own home areas. In addition to the various assistants, interpreters, drivers, veterinary scouts and so forth, who are drawn from the local population, the administrative officers (the DC and DO's) have direct command over the local Administration Police. During the colonial period the Tribal Police, as they were then called, were composed almost entirely of men serving in their own home districts, but since independence some ethnic diversity has been introduced into the local police units stationed at administrative offices. The functions of the Administration Police include assisting in tax collection and maintaining order at government offices, local courts, and public meetings.

District Office, Bomet, 1966

With independence local governments were established to replace the dual colonial pattern formerly found in areas such as Kericho that had a County Council dominated by Europeans settlers (with some Asian members) and a separate African District Council. The present County Council meets in Kericho. There area also Area Councils for the various divisions of the district. The district is also divided into constituencies for the National Legislature.

At the time of my fieldwork, most of the rural population fo the district could not be described as politicized. Politics was something that took place in Nairobi and Kericho and was not well understood, was not closely followed, and seemed of little importance to daily life. While this situation has undoubtedly changed with the increased penetration of the mass media into the rural areas, I think it is also fair to say that traditional patterns of behavior, in which no office automatically granted one man authority over another, each man kept his own counsel, and concensus was required for group action, frustrated early attempts at political mobilization in the modern sense.

On the other hand, the presence of the administration was clearly felt through such activities as the sub-chiefs', chiefs', and officers' meetings (barazas) and tax collection. The administrative structures inherited from the colonial government continued albeit with major shifts to new policies and new, African personnel who operated, as much as possible within the confines of their office, with a different style of administration.

Map 2

Kericho District Administartive Divisions, 1962

Map 2 shows the administrative divisions of Kericho District as defined in 1962. The identification of the various subdivisions shown in Map 2 are given in Table 1-3, below (government spellings are used). In 1963 minor changes were made on the western edge of the Sotik Scheduled Area (where Gusii farmers settled on former European estates), and in the northern borders of the Settled Area there. The divisions of the former reserve are virtually unchanged in 1965, with the exception that the former European areas of East and Central Sotik were included in Bomet Division, and North Sotik in Bureti.

| Map Identification (Location Number) | Location Name | Division | Population Density, 1962* Persons per mi2 |

1 | Belgut I | Belgut | 332 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Belgut II | Belgut | 350 |

| 9 | Belgut 9 | Belgut | 117 |

| 3 | Buret 3 | Bureti | 395 |

| 8 | Konoin | Bureti | 215 |

| 4 | Sot | Bomet | 270 |

| 5 | Mosop | Bomet | 274 |

| 6 | Chopalungu | Bomet | 197 |

| 7 | Soin | Bomet | 268 |

| A | Kericho County Council Wards (tea estates) | 296 | |

| B | Sotik (3 parts) | ** | |

| C | Kericho County Council Wards (Settled Areas) | ** | |

-

* Morgan and Shaffer (1966:20)

- The hilly areas which include most of the district lie in the Kikuyu/star grass zone. Marked by soils of red volcanic loam, the area was originally forested and is now very fertile farmland with pastures of thick green grass ("kikuyu grass" or "star grass") almost like lawns. Very few indigenous trees remain. Instead various European and Australian species (especially wattle and eucalyptus) have been planted among the plowed fields and pastures causing several observers to comment that this area looks more like the English countryside than a part of Africa.

- The impeded drainage zone comprises most of Bomet division, especially Locations 6 and 7, most of Central and East Sotik, and the western and southern portions of Location 4. Here the land is lower in altitude and flatter than in the Kikuyu/star grass zone and rainfall is less and is less consistent. The soil is heavy black loam (sometimes called cotton soil, though no cotton is grown in the district) overlying laterite. Thus in the rainy season the ground tends to become waterlogged or swampy. This rolling parkland is covered with several species of coarse grass growing to a height of two or three feet, often in clumps (though much of this area is now overgrazed). Dense clumps of trees and bush, ten to thirty yards in diameter, dot the landscape every fifty to one hundred yards. In the southwest is the Chepulungu Forest, now being cleared and settled.

The impeded drainage zone is quite favorable for grazing, and natural salt licks occur in several places. Experiments at Bomet demonstrated that cattle could be kept at a density of two per acre in most of this zone by using a system of rotating paddocks (Kenya Government 1956:167); actual densities in the research area were about half that. The zone has not proved suitable for cash crop farming, at least with the crops presently grown in the district, except in those few cases where mechanized equipment, extensive drainage ditches, and chemical fertilizers have been used. In 1967 there was an attempt to start a wheat scheme in the area after feasibility tests showed positive results, but the scheme failed to materialize for lack of support among the local population. The agricultural techniques used in this zone at the time of my research (ox-plows and hoes) limited production to little more than a subsistence level.

- The Maasai grazing zones, at the extreme north and south of the district, are lower and dryer still. Soils are black loam and clay with a coarse grass cover and some bush. Fencing is done with euphorbia (cactus) plants and millet and maize are grown for subsistence, though maize in this area is always a gamble. Here animal husbandry is most prominent.

** These areas have since undergone extensive resettlement

Variations in altitude, rainfall (Map 3), and soil combine to define three major ecological zones within the district (Pilgrim 1961):

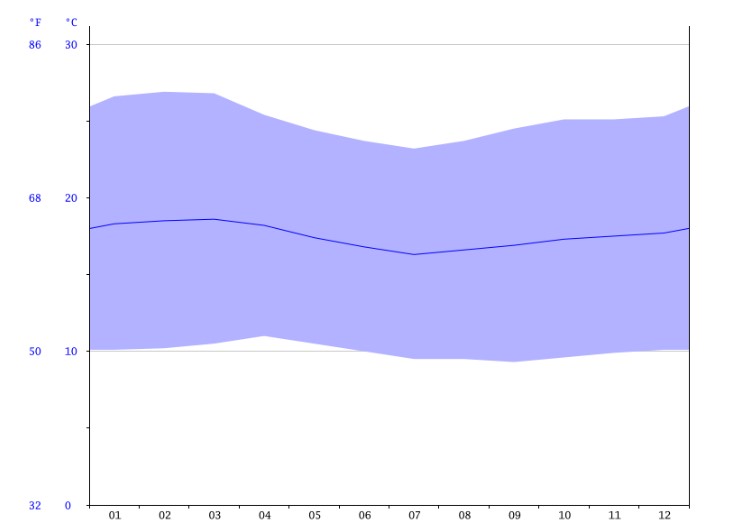

Bomet, Annual Temperature Range and Rainfall

source: en.climate-data.org/africa/kenya/bomet-104681/

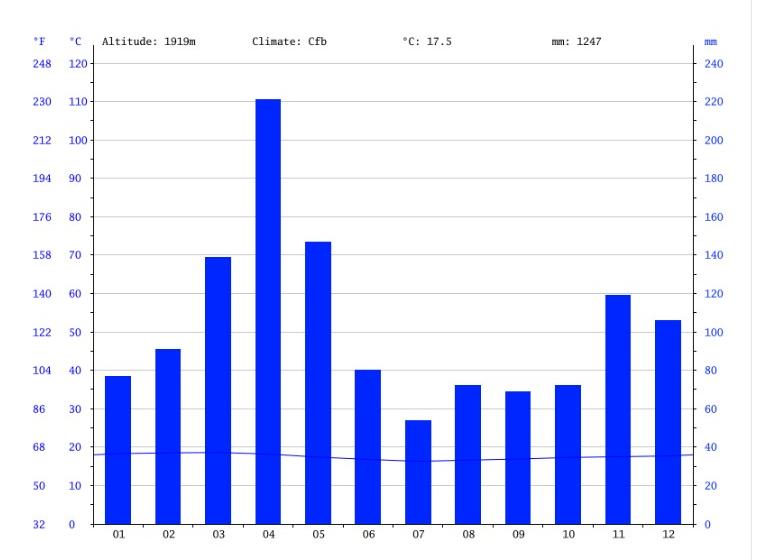

The Kipsigis speak of the ecological variations in their district using four basic terms.8 Strictly speaking these terms are relative, referring to directions away from the speaker rather than to fixed locations. But given the regularities of altitude, soil, and rainfall gradients, and their covariance, terms for direction naturally denote ecological differences in an approximate or unbounded manner. Mosop refers to land at higher elevations, and is thus associated with the fertile hills where, in the past, the bulk of the dependent population, gardens, and milk cattle were kept. Etymologically the term means "nothing but prosperity" (Orchardson 1961:3). Land at the same elevation or slightly higher than the speaker, particularly bush land opened by grazing and cultivation, is referred to as embwen (en, in, and kwenet, the middle ), while lower land used to produce grain is referred to as waldai (ke-wal to exchange, dai/tai away from the speaker ). Waldai is thus most often used to refer to land in the direction of the Sondu River, i.e. western Belgut. Lower land, in the opposite direction from mosop, is called soin (from soi/soito, grasslands [Huntingford 1935:133; Orchardson 1961:2-3]). The term is related to the term Sot which is used in everyday speech instead of Bomet as the name of the southern division of the district. Sotik (literally the people of Sot ) is the colonial name for the township and adjacent area on the northwest corner of Sot which the Kipsigis call Chemagel.

Sketch and Satellite Image of Kipsigis Area

source: Google Earth

This pattern of divided land use is reported by all the major authors on the Kipsigis and was confirmed by my informants. It is, however, a reconstruction. As population increased in the twentieth century, and as the use of plows, planting of maize, and enclosure of fields spread, the settlement pattern in the reserve became more and more homogeneous. Today both the hill and lowland areas are almost totally divided into family farms of ten to thirty acres (with the size of the average farm in inverse proportion to the fertility of the locality).

The extent of the old kaptich pattern cannot be easily determined and I feel it was never as extensive or dramatic as the dual grazing patterns reported for other, more fully pastoral groups in East Africa. Considering local topography, the kaptich pattern probably involved many small shifts between nearby areas (particularly in the central parts of the district) rather than a few large shifts between distant areas. Moreover during the nineteenth century Kipsigis population was increasing and this expansion led to the establishment of new homesteading groups on the fringe of the older domestic areas, with the cattle grazing sites (kaptich) not far afield. This is the pattern seen today just across the Maasai border where Kipsigis expansion continues (despite government attempts to check it) without the transforming influence of cash cropping and land enclosure.

Today people living in the lowland areas (soin) are hard pressed to find grazing for their cattle during the height of the dry season. If they are fortunate they will find an available pasture with a relative in mosop. In other cases they may have to rent such pasturage. Throughout the period of fieldwork both the soin and mosop zones of Bomet Division were under a foot and mouth quarantine and to move several animals at once risked arrest and heavy fines. Nonetheless I have encountered many herds, 20 to 50 in number, being moved at night along back roads between the two zones. It also seems clear, although I was unable to collect specific details, that the system of private cattle partnerships, kimanagan (discussed in Chapter 2), is used to make seasonal adjustments in cattle distributions. In extreme cases, however, families in the soin zone are forced to sell cattle, or butcher them for sale, for a small fraction of their normal price during the latter part of the dry season and then attempt to rebuild their herds after the rains with the proceeds of their harvest, when cattle are at a maximum weight and prices are high.9

While population pressure and the economic changes directly related to it have eliminated the system of divided herding in its more overt form, the Kipsigis long avoided the most significant effect of rapidly increasing population, extremely high density on agricultural lands, that marks other highland groups such as the Logoli, Gusii, and Kikuyu (Munroe, Munroe, and Daniels 1969).

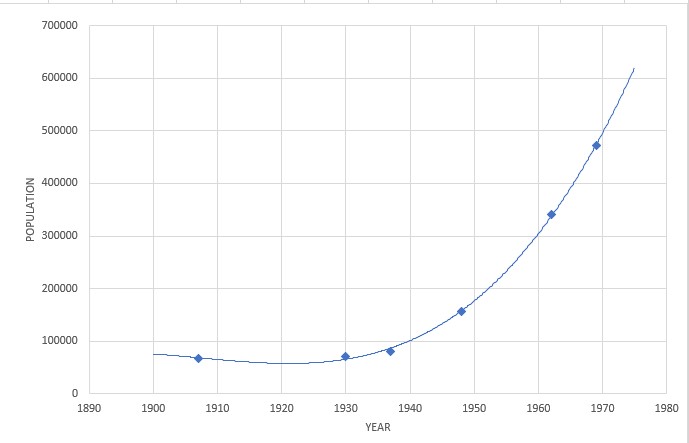

Kipsigis population growth, however, has been dramatic even if one considers the early figures to be very rough estimates.

| Date | Population | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1907 | 68,000 | Kenya National Archives Kericho District Report, 1906-07 |

| 1930 | 71,755 | Kenya National Archives Kericho District Report, 1930 |

| 1937 | 80,000 | Peristiany (1939:1) |

| 1948 | 157,211 | Pilgrim (1961:33) |

| 1962 | 341,711 | Kenya Government (1968:15) |

| 1969 | 471,459 | Kenya Government (1971:15) |

During the colonial era the Kipsigis were able to accommodate these increases by expanding to large tracts of previously unused or very thinly settled areas within the district. At the beginning of the century, the Kipsigis effectively controlled an area slightly larger than the present district, but the actual area of permanent settlement was about one-fifth of that, the rest being grazing land, forest, and other unoccupied areas (Pilgrim 1961:33). Expansion out of this core area in the hills, and the population movements resulting from European occupation of much of this older, settled area, has now filled all but a few remote corners of the district. Pilgrim (1961:36) estimates that the population density within the area of actual settlement around 1900 was 143 to 200 persons per square mile, while the 1948 census yields a figure of 175 per square mile. The 1962 census revealed an average density of 264 per square mile in the former reserve and 183 per square mile for the district as a whole (Morgan and Shaffer 1966:20). The overall density of the district in 1969 was 254 persons to the square mile, including non-Kipsigis (Kenya Government 1971:14). While population density in the former reserve has been offset in part by migration outside the district (mostly in the form of migrant labor in which younger men are heavily represented) and by middle and high density resettlement schemes for Kipsigis on much of the land previously owned by individual European settlers, it is apparent that in the next few decades Kipsigis communities will undergo changes of a qualitative nature much more significant than the quantitative changes of the recent past.

The geographic variations in modernization in Kenya have been described in great detail by Soja (1968). The present situation is, of course, a legacy of the colonial period when attention was focused on the areas of European settlement (the "White Highlands" now called Scheduled Areas or Settled Areas). Soja also notes that the developments in this "European subsystem" has a "lift-pump" effect on the adjacent African populations leading to

The impact of modernization was therefore highly uneven. Traditional social and economic organization, pre-European patterns of migration, and perhaps most importantly, geographic proximity and accessibility to the major nodes and flow lines within the new circulatory system affected the degree to which various peoples of Kenya were exposed to and transformed by the processes of change (1968:101, emphasis in original).

Kericho District as a whole stands relatively high on Soja's overall measurement of development. This is primarily due to the concentration of tea estates and European farms around Kericho township (the former estates in the Sotik area were in many ways isolated from the core of the White Highlands, were in a less fertile zone, and were not marked by the intensity of modern agriculture found in the other European owned areas). It should be noted, however, that the Kipsigis are a minority among the labor force on the tea estates, though their proportion is growing (estimated at ten per cent in 1958 and twenty percent in 1962 [Manners 1967:300]). And although the vast majority of the former laborers on the European farms in the northeast part of the district (around Lumbwa and Kedowa) were Kipsigis, the number of Kikuyu in this area has increased greatly in recent years, particularly on those former European farms that have passed into African hands outside the system of government resettlement schemes. Within Kericho District the degree of modernization varies from the northern area around Kericho town and the Scheduled Area, which Soja classifies as part of the "participant area" of Kenya (beyond the "core area" of Nairobi and the "national nuclei"), the vast majority of the former Kipsigis Reserve that he classifies as within the "effective national territory," to the extreme southern part of the district along the Maasai border, which is termed a "transitional zone" (Soja 1968:108).

This variation within Kericho District is discussed in detail by Pilgrim (1961) and Manners (1967) and is mentioned here only in brief. While it is an accident of geography that the agricultural fertility of the district shades rather evenly from the high area in the north and east to the low areas of inferior soil in the south and northern fringe, it is, of course, no accident that the tea estates developed in the most fertile regions with the highest rainfall, or that the majority of European settlement was nearby. Thus within the district there is an intimate relationship between proximity to the areas of greatest colonial development and the relative agricultural potential of the land.

As agriculture has become increasingly important, the disparity between the mosop and soin zones has increased and will undoubtedly continue to do so as new crops, such as tea, have been introduced to those Kipsigis living in the most fertile areas. The lowland area, which was once favored for its grazing potential, is now seen by most people as less fortunate. One man summed up the situation with the saying "after a while the shade will be on the other side of the tree."10

Within the mosop zone, Belgut, with its proximity to Kericho town, the tea estates, and the main road to Kisumu, appears to be most heavily influenced by the "European subsystem" of modernization. But it is in Bureti that agricultural modernization has been strongest. It was around Cheborge, in Location 3, that cultivation of maize with plows and land enclosure first appeared (Pilgrim 1961; Manners 1967). Today Location 3 has the highest population density in the district:

Although land enclosure had taken place throughout almost all of Bomet Division (Sot), by the mid 60s, the area was much less involved in cash crop farming. Throughout the low area, soin, almost all families were farming only slightly above a subsistence level with a minimal cash income from occasional sale of an animal, small amounts of milk, or a minor crop such as tobacco (or for a few localities, potatoes), or from wage labor most of which is outside the division.

As my main concern was the nature of traditional Kipsigis stereotypes of neighboring groups and the relationship of these stereotypes to their self-conceptions and other aspects of Kipsigis culture, I decided to focus my research in Sot. Within Bomet Division there was no available housing in the former reserve areas, and the Provincial Commissioner generously offered me the use of an unoccupied house on the edge of Bomet Trading Centre.

Now a County seat, Bomet at the time was not large enough to qualify for the designation as a town, Along with the District Office and associated officers houses and a line of rooms for the D.O.'s clerk, driver, and associated local police, there was a national police station with a sub-inspector, a sargent and about a dozen constables, some with wives and children, and a Catholic mission run by a Dutch priest. An American evangelical mission station operated a hospital a few miles away which served many tens of thousands of people.

The commercial area of Bomet consisted of two parallel streets, about a hundred yards long, one lined with shops and the only partially built up. There were a half dozen Kenyan Asian families operating shops and two gas stations, along with a couple African operated businesses, a cafe and a bar, and transient sidewalk enterprises: a tin smith (recycling bits of dead vehicles into kerosine lamps), an herbalist, and men dealing in the repair and resale of old radios, watches, shoes, or bicycle tires. The most prominent Asian family were descendents of the first peddler who arrived sometime before 1910. In addition to their shop, they ran a large panel truck which supplied small rural African shops ('dukas') with bolts of Jinja cotton, batteries, sugar and tea, cooking oil, kerosine, simple school supplies, aspirins, bicycle tire patches, etc., etc. They also ran a diesel powered mill for grinding corn brought in by farmwives, and installed the only electricity in town by running a wire down the street to their bar. A major part of their business was the wholesale trade in potatoes which they bought from hundreds of surronding farms and then transported to Nairobi in a fleet of 15 or more large trucks (which in turn created employment for drivers, loaders, and two mechanics - though none of them were Kipsigsi). Local conditions allowed for harvesting through much of the year. For the Kipsigis, potatoes were a cash crop, brought to town on donkeys, or backpacked by women. None of the local population ate potatoes and they were not offered in the small Sunday market. During the period of my fieldwork, one of the banks in Kericho started sending a Land Rover at the end of the month which would park in a vacant lot and serve as a branh bank for a day (truly a drive-in bank). A couple times a company showed up with a van, a generator, and a 16mm film projector, set up a sheet on poles and projected movies (1930s American cowboy films) and commercials for such things as soap and margerine for a small crowd seated on the ground. In 1967 a self-help (Harambee) project built a health clinic which was then staffed for a day or two each month by a government nurse.

During my initial months in Boemt I acquainted myself with the surrounding areas, began to learn the language, and started interviews, using interpreters, with very old men and women in various places in both the mosop and soin zones of the division. In the fifth month of fieldwork I decided to concentrate intensively of the community of Kapsuswek11 in Itembe, a lowland area not far from Bomet, where my best informant lived, and where I had made many contacts and attended initiations.

Itembe is a 10,000 acre tract of land that lies just within the impeded drainage zone. The line separating the black soil of Itembe and other soin areas to the south and west from the red soil of the Kikuyu/star grass zone passes close to the eastern edge of Itembe. The lowland areas of Sot were the last areas of Kipsigis expansion before the establishment of colonial rule and the first official delineation of Kericho (then Lumbwa) District. During much of the last century the area was under Maasai control. Many of the place names are of Maasai origin, and some of the oldest men I interviewed remembered stories of battles with the Maasai in this general area. Kipsigis control over Itembe and the area to the south was probably not secured until late in the last century.

Itembe is unique from surrounding areas in having been briefly alienated from African ownership early in the colonial era and then left virtually uncontrolled for decades before being surveyed and resettled by Kipsigis smallholders under the direction of the colonial government in the 1950s. This peculiar history resulted in a situation which proved highly fortuitous for the administration of standardized interviews discussed in Part II. On the one hand the area is indistinguishable in almost all respects from adjacent areas in the former reserve. Indeed, it was not until I was well into a focused study of the community of Kapsuswek (including construction of a house to be used by my interpreter and myself a few nights each week) that I learned of these circumstances. On the other hand, the discovery that the files of the Bomet divisional offices contained a map of plots in Itembe and a register of the Kipsigis originally resettled there greatly facilitated my census and genealogical survey and proved invaluable in deriving the interview sample. No map or register of farms, however outdated, was available for any other part of the division except settlement schemes just being established.

The current inhabitants of Itembe were able to tell me only the broad outline of its history. A Kipsigis friend living elsewhere in the division happened to have a copy of a publication (Kenya Government 1956) that provided some of the basic facts concerning Itembe's resettlement. It has only been since fieldwork however, that I have been able to learn some of the details of resettlement policy from archival materials.

Originally Itembe was defined as two plots in the block of estates known as East Sotik that cut between the western halves of Bureti and Sot. The area was first surveyed in 1906 and formally alienated from the native land unit by 1909 though the major European occupation of the Sotik area came after World War I as part of a series of "Soldier Settler Schemes" designed to attract British veterans to Kenya.12 Although the plots that form Itembe area described in the early District Annual Reports as having had two owners, the Kipsigis remember only one, whom they dubbed Kiptombuliet, "Paunchy" (from the 'Swahili tumbo, stomach,?), and for whom the oldest residents at the time of my fieldwork had worked as "squatters" or resident laborers. The site of his home is remembered, though none of the original buildings remain. He died after a brief occupancy some time in the early stages of European settlement; as early as 1920 the District Commissioner had recommended that the estate be returned to the reserve (Kenya Land Commission 1933:3:2460).

During the colonial era little commercial agriculture was done on the other, occupied, estates in Sotik. Most of the land was left unimproved. The European settlers placed emphasis on the development of herds of dairy cattle ("grade cattle") and left large expanses of their estates for grazing native cattle. Several times the Europeans insisted that the reserve was more than sufficient for the needs of the Kipsigis and pressured the colonial government to alienate further tracts of land, including the extensive Chepalungu Forest (which was ultimately homesteaded by the Kipsigis). It is clear, however, that even before the recent expansion of population in the reserve the prime grasslands of East Sotik were critical for Kipsigis herds:

During Kiptombuliet's tenure Itembe remained undivided and many Kipsigis previously resident there continued to maintain grazing rights through such work contracts. Following his death the area was used for communal grazing and an increasing amount of homesteading by families from the adjacent hills. Informants reported that no controls were maintained by other settlers and that eventually the area became Crown Land.

In 1949 Itembe was purchased by the African Land Development Organization (ALDEV), and was included in a land exchange agreement in which certain areas near Kimulot, just south of Kericho, were alienated for tea estates. Plans were drawn up for the supervised settlement of Itembe. The original plans foresaw development "with a pastoral bias" and included a series of measures designed to promote progressive animal husbandry practices and farming. Two hundred acres were set aside for a Veterinary Development Livestock Improvement Centre and twenty acres for an experimental farm plot. On the basis of studies carried out here, particularly the finding that one acre of land could support two head of cattle, it was decided to divide the rest of Itembe into thirty acre family plots (with a few smaller plots along the river that forms one of its boundaries.) Three hundred and fourteen farms were surveyed, each connected by "feeder roads" to the main motor vehicle road cut through the middle of Itembe, along with four small dams and catch basins, public watering places along the river, and plots for a school and shops. The survey also established an air strip near the Bomet Police Post and five "bull camps" of about ten acres each, scattered through the area. These bull camps were stocked with sihewal bulls to be used in improving the strain of local cattle.

In 1954 the government halted further homesteading in Itembe. The government chief and a committee of the African District Council then screened the residents of the area. Those who had once been resident laborers on the estate were allowed to stay on while plots were surveyed, while everyone who had arrived since September, 1953, was evicted. By 1955 the number of "illegal squatters" had been reduced to "200 which will be roughly the eventual number of settlers" (Kenya Government 1956:167). The number here refers to heads of homesteads, and a preliminary estimate of forty acres per plot. Following experiments at the Veterinary and Agricultural stations, thirty acre plots were demarcated instead.

The allocation and occupation of holdings started in August, 1956, and was carried out in stages over the next year and a half. The Allocation Committee received approximately a thousand applications. In addition to giving priority to old residents, thirty plots were reserved for men serving in the Army and Police. The remaining lands were given to "suitable people who are landless" (Kenya National Archives, Kericho District Annual Report 1956:17). Eight plots were assigned to widows, and no doubt many other cases were truly needy. On the other hand, many of those chosen were members of families that were prominent by the traditional standards of polygyny, cattle, and connections whose desire for land was a product of past family success rather than hardship. Although comparable data for other communities are lacking, and thus no quantitative comparisons are possible, it appears that the people resettled in Itembe represented a reasonably broad cross-section of the wider population.

Of the 311 original settlers listed in the register, 141 (forty-five per cent) gave Itembe as their place of origin. Most of the others came from nearby, with only a few families coming from outside Bomet Division.13

An analysis of the genealogical data from Kapsuswek supports informants' statements that they were given a large degree of choice among the plots available at each stage of the occupation of the scheme. In many cases the new resident occupied a plot adjacent to that of his father, brother, father-in-law, sister's husband, wife's brother, wife's sister's husband, or clansman, exercising choices similar to those of newcomers to established and traditionally organized communities.

In addition, a great deal of intermarriage has taken place among close neighbors since settlement. Perhaps more often than would be the case over a similar span of time in communities in the reserve, if only because the influx of many families resulted in more marriageable partners close at hand. The community patterns that have been established are discussed in detail in Chapter II. It is sufficient to note here that the Kipsigis do not have localized descent groups larger than the homestead group, and that marriages are typically arranged between families which have known each other for some time.

Thus both in terms of the distribution of farms by size and relative wealth of families, and the spatial arrangement of consanguineal and affinal ties, the settlement of Itembe did not result in community patterns much different from those elsewhere in the district. The lack of contrast with surrounding areas is best understood when it is noted that for most of these areas, particularly the soin lands to the south and west (Locations 4 and 6), a similar transition from a few original settlers to the present pattern of a continuous expanse of enclosed farms has taken place within living memory, and that large areas of Location 6 were not settled until after World War II.

In contrast to this natural social development, the plans for the controlled economic development faltered. In 1957 settlement rules were issued in Kipsigis.14 Settlers were required to fence their perimeters with sisal or mauritius thorn hedges. They were also limited to fifteen "stock units" per farm (or, according to my informants, forty head of cattle of various ages). In addition, sheep and goats were to be excluded. In 1958 a primary school was opened with missionary support, and a creamery which generated a small cash income for some residents. These have persisted with the school now under government sponsorship and the creamery, equipped by UNICEF, supplying the school with free skimmed milk while selling the cream to the national market. The Veterinary Department has also maintained a regular program of inoculating and branding cattle. Other aspects of the program did not go so smoothly. Although I know of only one case of a settler who was evicted during the early stages of the scheme (for refusing to enclose his plot), twenty-two others were threatened if they did not make improvements. The major problem, however, was not foot-dragging by a few individuals, but the classic issue of destocking. Attempts to enforce a reduction of family herds were hindered by the frequent closure of the nearby sale yard because of hoof and mouth disease and, no doubt, by the very different strategies of herd management deeply rooted in a society unaccustomed to enclosed grazing.15

In 1958 the bull camps were stocked, an artificial insemination program started, and "the herd on the experimental farm was in splendid condition throughout the year, and provided a fine example of the consequences of good grazing control" (Kenya National Archives, Kericho District Annual Report 1958:24). But this initial success had little lasting effect on the smallholders as efforts to direct their economic lives were relaxed in the last years of the colonial era. The original restrictions on people settled in Itembe appear to have been totally forgotten since independence. In 1965 every homestead kept sheep and goats, and several family herds numbered over forty. Cattle were grazed regularly on the unused, and badly rutted airstrip and along the roadways, a practice which would have drawn heavy fines during the colonial period. Even at those homesteads with smaller herds the general opinion was that the grass cover was overgrazed, as could readily be confirmed by glancing at those few areas (e.g. around the drainage basins) where cattle were excluded. Similarly, agriculture is no more advanced than in other lowland areas outside Itembe. None of the people I spoke with showed any awareness of the results of the agricultural experiments carried out years earlier in Bomet. Homestead maize plots varied from one and a half to two and a half acres, supplemented in most cases by smaller plots of eleusine millet (bek,'Swahili 'wimbi') and vegetable gardens. In most years the family granaries were exhausted before the next harvest and maize was bought from hill areas on the black market.

By 1965 about ten per cent of the farms had been sold, some of them in pieces. Other farms had been subdivided by heirs. Many more such cases had occurred by 1972, when I last visited the area and no doubt as the second generation of occupants reaches full maturity the increased population pressure on the land and the rising cost of basic necessities will lead to many more cases of subdivision (despite a Kipsigis value against dividing land into units too small to support an independent homestead). A few of the original settlers have also managed to acquire a second plot, and there are one or two examples of men who live in the higher zone who have bought a plot in Itembe to use as supplemental pasture.

By 1965 the Livestock Improvement Centre in Bomet was used for grazing a small government herd consisting primarily of cattle confiscated by the police in connection with various cases. There was no indication that the Veterinary Department was using the herd for experiments or attempts to improve private herds in Itembe. A cattle dip built as part of the original centre had not been used for some years (however the people of Itembe had constructed a dip in the center of their area a few miles away). Although an artificial insemination program was being operated on a national level, using thoroughbred bulls kept at Kabete, near Nairobi, it was confined in Kericho District to the post-independence settlement schemes, Indeed the bull camps in Itembe were no longer stocked. One had become the site of a make-shift nursery school started by local contributions of money and labor. The others had either been incorporated into adjoining farms or were being used as communal grazing areas. One man in Itembe tried repeatedly to raise European dairy cattle, but despite his efforts at spraying them with a hand pump, they died of tick-borne diseases.

In summary, Itembe today differs little from most surrounding areas. The particular features of the original settlement have long been abandoned, and the current development of the area, such as it is, is following the same course here as in other areas: subchief's meetings every few weeks, a rare visit by an assistant officer from Bomet, and a series of minor, individual efforts at self-improvement. The developments that have taken place have been social: the establishment of communities and networks of interfamily ties of the traditional type. Aside from the relative homogeneity of land holdings, and a map of the farms as originally surveyed, Itembe does not differ significantly from the neighboring areas which have developed without the benefit of a special government program. This is clearly marked in the speech of the residents of Itembe and surrounding communities who refer to it as part of the reserve ("reserb," a legally outdated term) in contrast to the settlement schemes ("segiim") of East Sotik where estates continued to be operated by European settlers until 1961 and where, with independence, a major land redistribution program has created a new economic order with heavy emphasis placed on cash crops and dairy cattle, to the exclusion of native cattle, supported by resident government officials, well capitalized cooperative societies, and for the thousands of new smallholders the pressures of keeping up with ten year development loans and thirty year mortgages (see Cosnow 1969).

2 Kericho District was divided in 1992 to form Kericho County and Bomet County.

3 Heine (1970) presents a succinct review of the Nilo-Hamitic issue. The central exchange was between Hohenberger (1956, 1968) amd Greenberg (1957).

4 The spelling of Kipsigis terms in this work follows the orthography developed by Charles C. Ng'elechei which has been adopted by the Kalenjin Language Committee. This orthography is not strictly phonemic, but incorporates a stanardized set of usages first introduced in various mission schools. Different symbols are used for allophones of the following consonantal phonemes:

Other consonants that are represented by symbols other than the usual phonetic symbols:

There are eighteen distinct vowel phonemes in Kalenjin, which can be represented as the five basic vowels, each of which may be long or short, and open or closed (intwo case sthe possible value is phonetically indistinct from another, logically different vowel). Vowels are represented in this orthpgraphy by standard English symbols. a, e, i o, and u. Closed /a/ is written as o. Length is now show except in a few instances where a long vowel is written with two symbols, e.g. beek (be:k). Because of the previously introduced spelling systems, this orthography usually does not indicate regular consonantal assimilations, though two spellings of some words are recognized, e.g. chepyoset (chep + yoset), old woman, or chebioset, which more closely indicated the actual pronunciation. For a full discussion of Kalenjin phonetics see Tucker and Bryan (1964, 1965).

"Kipsigi" is an error frequently made by non-Kalenjin speakers in Kenya, putting the term in the consonant-vowel pattern of 'Swahili syllables, and by native English speakers mistaking the terminal "s" as a plural form.

5 As discussed in Chapter 4, the term Lumbwa now has a different, but still derogatory meaning for most Kipsigis.

6 This description refers to the time period of my fieldwork, 1968-1968.

7 In 1902 the area was transferred from Uganda to the East African Protectorate as Lumbwa District. It was renamed South Lumbwa District in 1921 and Kericho District in 1935. For details of these and other administrative redefinitions and boundary changes see Gregory et al. (1968).

8 These terms occur, with some variations, among all the major Kalenjin groups.

9 I could find no evidence that any of the people in the hill areas regularly speculated in this short term fluctuation in cattle prices.

10 While the transformations between 1965 and 1995 in housing and material possessions that I witnessed in the highland mosop areas were truly amazing, I was equally surprised that for some of my old friends in soin circumstances were utterly unchanged: round thatched houses, cooking over an open fire in central hearthstones with a few aluminum pans, a kerosene lamp, a creek for the water source, no outhouse, etc. Indeed, these scenes were much the same not only in 1965 but, I suspect, 1935. Obviously many factors are involved in such inequalities, but primary among them are the extent to which one's farmland can support cash crops, control of family size, and access to education and employment.

11 A pseudonym, "place of grasses."

12 The European population on the Sotik estates increased from thirteen in 1920 to "over a hundred" by 1932 (Kenya Land Commission 1933:3:2418).

13 It should be noted that none of the original settlers came from the area near Kericho that was alienated at the same time. While the "Kericho Land Exchange," which involved the transfer to or from African ownership of six tracts of land may have seemed a balanced transaction on paper and in the minds of higher officials who thought of the "tribe" as a corporate land holding unit somehow analogous to the government, the arbitrary effects of this exchange for hundreds of individual families must have been evident to the officers in the field.

14 Ten years later half my sample reported that they could not read any Kipsigis.

15 The system of private cattle loans (kimanagan) is one of many traditional practices that work against destocking.