A REANALYSIS OF BANGWA BELIEFS

ABOUT BIRTH AND DEATH

A paper presented at the 9th Annual Meeting of the Southern Anthropological Society,

April, 1974 Blacksburg.

M. C. Bateson (1972:194)

Robert Brain, in an article entitled "Friends and Twins in Bangwa" (1969a), describes some of the beliefs concerning conception, birth, early childhood, and death among the Bangwa, one of the Bamileke chiefdoms in the highlands of West Cameroon. Following a short explanation of how he was introduced to the topic in the field, and some details of the beliefs, Brain demonstrates how this system of beliefs is the basis for a set of formalized friendships and egalitarian "twinships" which can be seen as functional in a social system in which adults are strongly differentiated according to age, sex, and achieved and inherited power.

In this paper I would like to discuss some other possible meanings of Bangwa beliefs which Brain does not stress.

In the discussion that follows, I am not trying to find a cause for Bangwa beliefs which determines that they be just as they are. Instead I wish to test the applicability for these data of "cybernetic explanation" as formulated by Gregory Bateson (1972:399-410). This approach conceives of a set of beliefs as a sub-system in interaction with various other cultural, and ultimately non-cultural, sub-systems which are the context of these beliefs. The least flexible aspects of a particular sub-system serve as restraints or sources of information for the patterning of other parts of the larger system (in this case the system beliefs-in-context). Any pattern which is communicated between parts of a system is partial information or a partial message about the nature of that system. Bateson defines the question of "meaning" as follows:

If then we say that a message has a "meaning" or is "about" some referent, what we mean is that there is a larger universe of relevance consisting of message-plus-referent, and that redundancy or pattern or predictability is introduced into this universe by the message (1972:407).I will attempt to apply these concepts to Bangwa beliefs concerning birth and death in four contexts of meaning which can be labeled, rather loosely, the logical, the sociological, the ecological, and the psychological.

This approach makes a basic assumption about the conception of cultural forms, an assumption which I believe is well established in anthropology. Put generally, it is that culture is an evolved, adapting and adaptive aspect of human existence. In this case the specific assumption is that a belief system which characterizes the thoughts of members of a society over time is an evolved statement of their relationship to some part of their world. Put more colloquially, it is best to start with the position that the natives know what they are talking about.

I will, therefore, first consider the explicit subject matter, the manifest content, of the belief system as a conscious rationale, or logical model of the world, in many ways akin to western science (Horton 1967). Later I will try to demonstrate that these beliefs have other implicit, latent, or metaphoric levels of meaning.

The Bangwa base their explanation of events involving birth and death on an opposition of the everyday world to

Efeng, the world of unborn children ... a vast black cave, peopled by the spirits of children who wander around in pairs or groups looking for suitable parents.Children have to be seduced from efeng into their mother's womb. In some cases they go in pairs and are born (in the ideal case) as twins.

... the supply of children's spirits is constant, being replenished constantly by the spirits of dead Bangwa who are reincarnated in their descendants.

[If twins are born] and no special ritual is performed, one of the twins' parents or grandparents must immediately die to correct the imbalance in efeng (Brain 1969a:217).

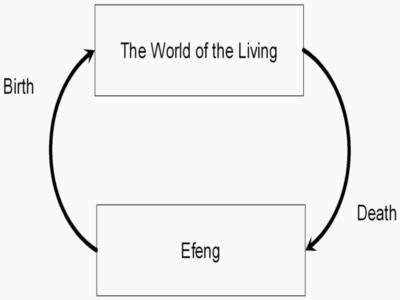

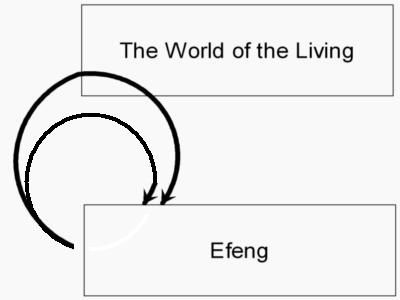

The relationship between this world and efeng, and between birth and death may sketched as shown in Figure 1 (below). This world is characterized by suffering, and is not the likely choice of a free (disembodied) spirit. Multiple births are said to create an imbalance in efeng which threatens to draw an adult out of life. The belief system does not specify a fixed number of spirits at each point in the total cycle. Indeed, through ritual action the number of people in this world can be, at least temporarily, increased. The major concern appears to be the problems of maintaining our numbers in this life. It is not the carrying capacity of this world, per se, but the strong drawing power of efeng, of death, which is the problem, the limit or restraint which informs the whole cycle. The Bangwa see the key dynamic features of their reproductive cycle as being located beyond the control of their everyday technology.

The inverse of death is birth, not only processually but also qualitatively. While death is certain, successful birth is uncertain, and places living people in a struggle with the attractions of efeng. As Brain explains:

It is, however, rare for a spirit pair to agree to enter a single womb. Tastes differ and twins often separate at the last minute. Some enter a womb and remain there for some time before one decides to return to efeng. A child who has been convinced by his parents that life with them will be the best thing for him may be tormented by his twin, who lurks in the shadows or the fire burning in the hut of the pregnant woman, trying to seduce him back to efeng (1969a:217).

... children, who exhibit signs of chronic illness, are said to suffer from the tormentings of their "friends" in efeng who have not agreed to be born and who continue to seduce their friends along the road to efeng and the carefree life of the unborn children (p. 218).

In other words, pregnancy is a time of great anxiety, many pregnancies are unsuccessful, and children frequently fall ill and die. Establishing another person in this world is a series of high risk procedures, and it is problematic whether any new arrival is among us to stay for long.

If this reading of Bangwa beliefs is accurate, and if their beliefs are an approximate mapping of their reproductive situation, then it appears that the critical restraint operating on their population maintenance can be further specified as a high rate of prenatal, perinatal, and infant mortality.

In rare cases, however, people are not only successful in ordinary measure, but actually manage to induce a pair of spirit children to make the commitment to this world together:

Twins are wonderful children, likened to "spirit beings" and are called "children of the gods". They are thought to be endowed with the gift of seeing their way back to the world of unborn children (efeng).

The parents of twins assume special titles ... which give them the right to take up ritual office or practice as diviners (Brain 1969a:217).

Many societies in Africa, for example the Ibo (Achebe 1959), are reliably reported to have practiced infanticide of twins prior to western interference. Granzberg, using a worldwide sample, has demonstrated that twin infanticide is found almost exclusively in societies "where mothers have a heavy workload and where they have a minimal amount of help" (1973:411). The absence of twin infanticide does not necessarily imply a light workload or ready helpers according to Granzberg's data. But the strong positive value which the Bangwa attach to twins suggests that they do have regular ways of mobilizing labor and food resources for the support of twins beyond those available to the immediate parents. This attitude towards twins reiterates the idea that Bangwa reproduction is not seen as being limited by the capacity of this world to support children.

Just as the parents of twins are materially dependent on others for success in reproduction, they are expected to share their success by helping others with their difficulties through ritual office. In terms of both worldly resources and knowledge of the way to travel from efeng to life, there is a sense of "shared fate" linking twins to other children in Bangwa society. The way to manipulate the system to the advantage of the living, to offset the drain of a high loss rate at the start of life, is to recognize the "twinness" inherent in all children born to this world.

Children who are born without a twin are considered to be in a dangerous state; pairing them with a friend removes the danger that they will be seduced back to efeng (Brain 1969a:218).

Children are sometimes converted into the twin (lefak) category [a child with an unusual delivery or congenital peculiarity] after long bouts of illness. Once their propensity for dying has been removed ritually, they remain twins (p. 217).

It seems then that the Bangwa have a belief system which is not only logically consistent in its structure, but one which also offers ways of dealing with the relevant problems. But to say that a set of beliefs makes internal logical sense is to say almost nothing. Given the tendency of our minds to order perceptions and symbols, it is hard to imagine how Bangwa beliefs could not make sense on this level. To make sense in a wider context, to be meaningful as this concept has been defined here, a set of beliefs must contain patterns which are redundant for a larger pattern of relationships between the symbols and the world they attempt to map (Bateson 1972:132). What, for a start, do we know about the actualities of Bangwa reproduction?

Reproduction for the Bangwa, as for most societies, takes place primarily within the context of marriage. If a major restraint facing the Bangwa has been a high mortality rate, particularly among babies, one might expect to find marriage patterns which come close to maximizing live births.

Virtually all women in Bangwa are married, as is typical in Africa. More significantly, the Bangwa have a very high rate of polygyny:

"in a typical hamlet over 50 per cent of married adult males have more than one wife, while a paramount chief may have up to fifty at the present time" (Brain 1969b:13).

The question here is not whether monogamously married women of polygynously married women have more children, but how polygyny systematically influences the number of children women typically have in this society and how polygyny relates to the children's chances for survival.

First, a significant rate of polygyny is sustainable only if there is a significant difference in the age of marriage for males and females. Among the Bangwa, females are married very early indeed. Brain reports that

Girls are married shortly after puberty ... Once a girl, in a group of age-mates, is considered ready for marriage the parents of her age-mates prepare to arrange for the weddings of all their daughters, whatever their physical maturity, although a very immature girl may be 'fattened' for seven or nine weeks, on the advice of a diviner (1969a:219).

Elsewhere, Brain comments that women "go to reside permanently with their husbands from the age of twelve or thirteen" (1969:13). Such early marriage clearly makes maximum use of the childbearing years.

Second, polygyny is the unequal distribution of married women to married men. In this case it is clear that those men with greater economic resources in hand are those with more wives. High brideprice -- Brain gives a "typical" figure of £180 [approximately US$500] (1969:14) -- is a demonstration of this economic power. Thus many women, particularly second and third wives, tend to be married into those households most able to support them is their role as childbearers.

In addition, the Bangwa practice a complex system of wardship marriage in which a woman's guardian (tangkap) not only profits from his rights over her, but is also expected to contribute to her expenses, particularly at critical moments such as rites of passage, illness, and childbirth (Brain 1969b:18). The ideology of the wardship system, incidentally, is based on the past importation of female slaves who were married into Bangwa society (1969:20), another redundancy with the idea that it is desirable to increase the input of people into the living component of the total cycle.

In short, this brief look at marriage reveals several ways in which actions are patterned according to the major restraint identified in the discussion of the belief system. To demonstrate further that Bangwa beliefs are an evolved statement of their relationship to their world would require a great deal of information about their ecological situation.

In this case we must be content with much less than full data, in fact with just a few estimated rates of basic demographic functions. Such data are rarely available with the precision one would like. The available figures, given in Table 1, generalize for the Bamileke chiefdoms, of which the Bangwa are one. While such data are admittedly crude, they do indicate that the situation is extreme.

| Annual Rates | World** | U.S.A.* | Africa* | Cameroon* | Bamileke Chiefdoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Births per 1000total population | 33 | 17.3 | 47 | 43 | 50** |

| Deaths per 1000total population | 13 | 9.3 | 21 | 23 | 26** |

| Infant Mortatity per 1000 live births | -- | 19.2 | -- | 137 | 158*** |

Population Growth Rate |

2% | 1% | 2.6% | 2% | 2.4** |

* Population Reference Bureau, Inc. 1972 World Population Data Sheet. Washington, D.C.

** Podlewski, A.

1970 Aperçu général de la démographie de la République fédérale du Cameroun. Mimeo. [quoted by Elie 1971]

*** Hugon, P.

1968 Analyse du sous-développement en Afrique noire: l’exemple de l'économie du Cameroun. P.U.P. [quoted by

Elie 1971]

———

Elie (1971:2) cites a crude birth rate of 50 per thousand population, a figure surpassed on the national level by only three countries, all in Africa (Niger, Rwanda, and Swaziland, each at 52 per thousand), and an annual infant mortality rate of 158 per thousand live births, or one out of every six or seven. This is certainly a high figure though not atypical for Sub-Saharan Africa (of 31 Sub-Saharan countries 15 have higher rates and 16 lower, with a high of 216 for Guinea and a low of 115 for Zaire). By contrast, the three highest national rates of infant mortality outside of Sub-Saharan Africa are 149 for Morocco, 142 for Pakistan, and 139 for India (Population Reference Bureau, Inc. 1972). The corresponding figure for the U.S. is 19.2, or roughly one out of every 52 live births. Such figures, particularly for underdeveloped areas, should be considered very approximate, though most likely they err on the low side. A very high crude death rate, 26 per thousand total population, and a low life expectancy, 37 years at birth (Elie 1971:2) complete the picture of Bangwa adaptation as a response to high rates of mortality by means of a high rate of replacement. The high rate of population growth estimated for the Bamileke Chiefdoms, 2.3% per annum, also suggests a system which in the past has been tuned to producing live births at close to the maximum possible rate. Whether the imbalance reflected in this rapid growth rate, which is presumably related to the many changes introduced in this century, is due primarily to a decline from an even higher rate of mortality or to an increase in the birth rate, the rapid increase suggests that the traditional system did not involve strong internal controls on the birth rate per se but used high birth rates as an adaptive response to a relatively uncontrolled and uncertain context marked by high loss (Margalef 1968).

It thus appears that the Bangwa beliefs about their relationship to their environment, that this world is inimical to children and one into which they must be coaxed and protected by whatever means available, are an adaptive assessment of their situation.

I think it is also clear, though at this point the data limit us to speculations, that these beliefs are psychologically adaptive for Bangwa adults. The ritual actions associated with these beliefs probably have little or no effect on the psychological condition of the child in question, but do supply meaning to the feelings of those who frequently experience the death of their newborn and unborn children. The metaphoric message seems to deal with the necessity for mutual support in the face of such loss.

Consider the ritual necessary to protect parents and grandparents of healthy twins. It is certainly not a unique reflection that the birth of one's child or grandchild suggests that one's own time in this world is diminishing. This feeling of poignancy is probably heightened in a world where half of one's age-mates are dead when one is thirty-seven years old. The ceremony to protect grandparents from immanent death may thus serve some as a way of expressing reassurance to persons who are reminded of their personal obsolescence in the process of life.

But it would be wrong to suggest that the relationships expressed in any ritual have only one mood. If newborn twins threaten grandparents, it seems probable that it will occur to many minds in darker moments that longevity is this world threatens the vitality of the young. Indeed, Brain reports that among the criticisms of the institution of marriage wards frequently made to non-Bangwa authorities by those Bangwa with a "modern" orientation is not only a sense of economic exploitation but also (to quote one of his informants) "'It is the tangkaps [guardians] who are killing all the children in this country'" (1969b:19). Rituals are a metaphoric way of telling ourselves and each other what the world is about (Geertz 1973), including contradictions and disruptive ambivalent feelings such as these which could not have been overtly expressed in either the traditional political or psychological context.

Another ritual described by Brain, which presumably is used when attempts to establish a viable "twin" relationship for a sick child fails, is similarly suggestive:

The parents [of a chronically ill child] call in a ritual expert (tanyi, the father of twins' himself) to perform a ceremony to cut him off from his friend. An effigy is made of the child from a plantain stem; a deep pit is dug; the child is placed inside as if in burial but at the last minute before the pit is filled the child is whisked out and replaced by the effigy. In this way the unborn twin is fooled and will cease preying on his 'friend'. (1969a:218)

It seems reasonable to assume that a high proportion of the parents who take this step are faced, not long after, with the death of their child and an actual burial. The mock burial probably serves in many cases as a rehearsal for a very stressful event, as a way of structuring and inter-relating the feelings of grief, loneliness, guilt, despondency and so forth that are immanent in the situation. What more can one do than to relinquish one's child and yet snatch it back from efeng?

A belief system which makes such feelings communicable does not remove their cause, and does not diminish their intensity, but it does allow them to be connected systematically to patterns which recur throughout experience and thus to be acceptable, to make sense, to the individual mind.

Lest this discussion end with the impression that the Bangwa are in a situation of perfect homeostasis, I think it is necessary to mention again the exceptionally high rate of population growth among them and neighboring groups. The instability this growth suggests is most probably due to the introduction of medical technology without regard to its systematic impact. To the extent that modern "death control" is effective in Bangwa, the belief system described here will fail to reflect the new reality, and if this analysis is correct, one would predict increasing disruption or "noise" in their social practices and in their attempts to render events meaningfully to themselves and each other.

It is distressing to observe that medical intervention among "the natives" so often lacks the wisdom found in traditional belief systems, such as the Bangwa, that there is more to the context we depend upon than that which we directly observe and command.

Whether or not there is any efficacy to these beliefs, beyond whatever psychological protection they offer to parents, is beyond the scope of this paper. I will only mention that one of my students, an Igbo from eastern Nigeria, told me that the mock burial is done in his home community, but only if the child is two or more years old so that he or she "can see and understand that they have been redeemed" from the grave.