Real World Problems and Reflexivity

Ljubljana, Slovenia, August 28, 2008 - revised June 10, 2010

American Anthropology Association webpage, 2008

[Note: because many of the sites in the on-line references have changed or disappeared at the time this paper is being posted (December 2019) I have not made any of the hyperlinks operative]

It is now being widely recognized that the human species is on the brink of massive changes as great as those resulting from the rise of industrialization, and perhaps even as great as the changes brought about by the development of food production. The interlocked problems of non-renewable resource depletion, accumulating industrial waste, biosphere degradation, and climate change lead both expert and lay observers to postulate drastic predictions about the foreseeable future. The events being predicted for the coming decades and next couple centuries are, by almost all current standards, extremely negative: e.g. the replacement of democratic civil society by authoritarian police states, the permanent collapse of electric power grids resulting in the loss of all digitally encoded information, the collapse of industrialized food production and a "die off" of human population, etc.

Five times over the past several years I have offered a seminar course entitled "Anthropological Perspectives on the Energy Crisis." Anthropology (using the term in its inclusive American sense that seeks to combine human evolution, bioanthropology, archaeology, culture history, linguistics, and much more with social anthropology) is the social science that most fundamentally takes a global view, looks at the human species over the long (indeed evolutionary) scale, and has investigated the collapse of past civilizations with a comparative, multidisciplinary, cultural-ecological approach. The seminar examined the validity of the dire predictions of an energy shortage and climatic crisis. We also looked at various studies of the trajectories of past civilizations. And we searched for analyses in the social sciences, and particularly in anthropology, that might help us understand current processes and help us anticipate and prepare for the future. Surely, we asked, anthropological theory and research has so

To date the results of this quest have been slight. Rather than being centrally concerned with these issues, academic anthropology is largely silent, and seems about to be overwhelmed by the truly global transformations occurring among its own subjects, and to be rendered irrelevant. This paper is my attempt to explain why I think the discipline is not dealing with the real world (and a plea to colleagues to save me from my ignorance if there are anthropologists who are addressing the crisis).

In this section I mention facts and references which have influenced my thinking on these topics. I make no attempt to present complete summaries; I assume readers are familiar with the basic issues discussed here.

(Polycarpou 2005).

On a human time scale, the amount of fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas), both known and as yet undiscovered, is finite. Meanwhile worldwide demand is accelerating rapidly. Over the past several years a number of independent oil geologists have pushed awareness of the problems of fossil fuel depletion. The first article addressed to the general American public (or at least the general intelligentsia of America) appeared many years ago: "The End of Cheap Oil" by Colin J. Campbell and Jean H. Laherrère, in Scientific American, (March 1998). Six years later the same title was used in a lead article in National Geographic (Appenzeller 2004).

Campbell, a retired British petroleum geologist, went on to found ASPO, the Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas (http://www.peakoil.net/). 'Peak Oil'1 has become a major scientific focus, and propagation of public awareness about it has become a major social movement among a certain set of concerned scientists and citizens in many countries as well as spawning countless local "power down" organizations seeking practical applications for low energy lifestyles. (A Google search on "peak oil" will produce over 4½ million hits.) The problem is not that sooner or later we will run out of fossil fuels. The problem comes when we run short of oil. Global oil production cannot expand indefinitely and at some point production will peak. The term draws our attention to the fact that the critical transition will not be when oil reserves near exhaustion, but when worldwide production peaks and less and less oil can be produced no matter what effort or expense is made. At that point whatever the level of demand may be, the level of consumption worldwide will start to decline.2 Further, it is misleading to focus on the amount of oil remaining in the ground. We cannot recover all of the oil from any field, and we will never recover all of the 'recoverable' oil in the world since industrial society will have ground to a halt long before the last 100, or 1,000 or 10,000 barrels are pumped from the earth.

The title of Campbell and Laherrère's paper, "The End of Cheap Oil," also draws our attention to the fact while "the first half of the age of oil" has involved extraction of roughly half of the ultimately recoverable oil, the second half is qualitatively different, for the oil already extracted has been from the most accessible and highest grade resources, that is those with the highest energy return on energy investment (EROEI). The cost of recovery, and in many cases the ecological destruction necessary, can only increase.3

The central message of these "pessimists" or "Cassandras" is that the “peak oil” transition is not in the distant future but here now. A few years ago, many people considered "peak oil" simply wrong-headed and refused the basic premise of the analysis. But as Colin Campbell is fond of saying, this is something every beer drinker knows: "the glass starts full and ends empty, and the quicker you drink it, the sooner it is gone." In 1998 Campbell and Laherrère suggested 2010 as the rollover date. Others have moved this prediction forward or back a few years.4

In the past decade many others have considered these predictions wildly wrong, but recent events are producing new believers every day:

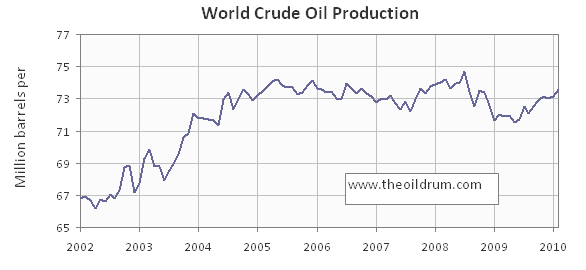

At just under 86 million barrels per day, global oil production has, essentially, stagnated since 2005, despite soaring demand, suggesting that production has already reached its geological limits, or "peak oil".

Pessimists believe that production has passed its peak. Optimists say it may be 20 years or so away - which would give us some time to prepare - but [they] are now muted. Last week [March 2008] the hitherto optimistic International Energy Agency admitted that it may have overestimated future capacity. Chris Skrebowski, editor of 'Petroleum Review' and once an optimist himself, believes that the world is now in "the foothills of peak oil". Prices may ease a bit over the next few years, but then the real crunch will come. The price then? "Pick a number!" (David Strahan, quoted in Lean 2008).

And this from the oil tycoon T. Boone Pickins:

The data do suggest that global production has reached a plateau:

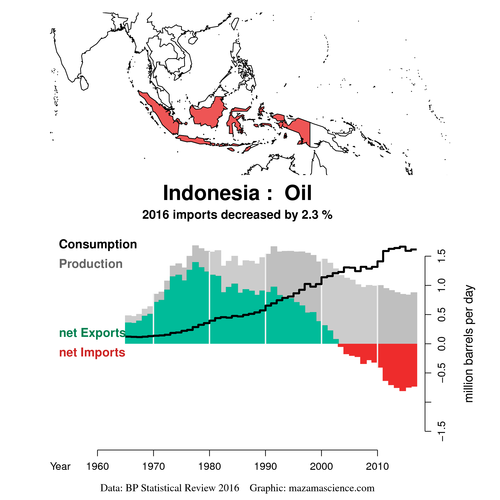

The problem of shortage arises, of course, from both diminishing reserves and increasing demands worldwide. Increasing, following the pattern of the United States, oil producing countries are also becoming major consumers. In some cases, as the following chart shows for Indonesia, they are already transitioning from exporters to importers:

Source: http://mazamascience.com/OilExport/

Barack Obama, Presidential News Conference, May 27, 2010

Michael Ruppert (2005) has been a leader among those who have argued that Peak Oil has long been an unstated central concern of western governments (and the hidden premise for American geopolitical policies) while publically the term was derided as a wrong-headed theory to be relegated to the margins of public discourse. Very recently there have been three events which indicate the extent to which this has changed.

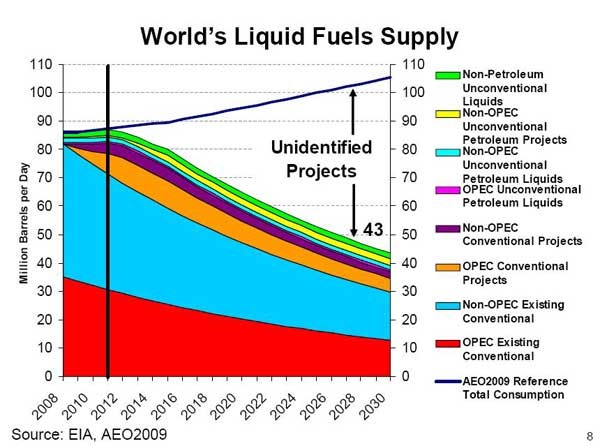

First, The International Energy Agency, based in Paris, scoffed at the idea of peak oil as recently as 2005, but “radically changed its assessment” between 2007 and 2008 (Monbiot 2008). In March 2010, the chief economist of the IEA, Fatih Birol, declared that the "era of cheap energy is over" (Barkley 2010). Indeed a decade earlier, in its World Energy Outlook of 1998, the IEA published figures which hinted at a peak in world crude oil supply [i.e. production] around 2014, but, as David Fleming (2009) and Lionel Badal (2010) have recently charged, the true nature of their projection was obscured by adding in a “balancing item” of “unidentified unconventional oil” in order to produce a ‘business as usual’ scenario of future economic growth. In the footnote to Table 7:12 on page 92 of the 464 page WEO 1998 report we read that “Unidentified unconventional oil is from currently unknown or uncertain projects.” Fleming now sees this needle hidden in the haystack as a “coded” message to the few. For Monbiot, the IEA’ s recent change of heart “should scare the pants off anyone who understands the implications” (2008).5

David Fridley, Energy Scientist, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (DOE) (quoted by Badal 2010)

Third, in the United States, a Joint Operating Environment report from the US Joint Forces Command released in April, 2010, stated "By 2012, surplus oil production capacity could entirely disappear...” (Macalister 2010). That same month the following chart, prepared in 2009 by Glen Sweetnam, director of the International, Economic and Greenhouse Gas division of the Energy Information Administration at the Department of Energy of the US Government, became public (Arguimbau 2010):

The US Government still refuses to use the term Peak Oil, speaking instead of an “undulating plateau” pattern, which will start “once maximum world oil production is reached” (Azzanneau 2010). From Figure 2, above, that seems to have been in 2008, or perhaps 2005. I suspect “Unidentified Projects” in Sweetnam’s chart is a euphemism for “Nonexistent Projects.”

And, of course, oil is only one of many critical resources becoming scarce.6

Many authors have analyzed the possibilities of alternate fuel sources (Heinberg 2005, Homer-Dixon 2008, Smil 2008, Bryce 2010, etc.). Some see a far greater role in the future for natural gas, though the abundance, accessibility, and ecological downside of ‘shale gas’ in the US is hotly debated. Others see a much greater reliance on nuclear power, which was originally, in the 1950s, and is once again touted as a stop-gap or transitional solution. At this point the amount of capital and time required for a major shift to nuclear generated electricity seems prohibitive. Then there is the question of “peak uranium” (see, for example, Storm van Leeuwen 2006). Heinberg (2005:148) suggest the nuclear fuel problem can be solved by building fast-breeder reactors, but “a smoothly-running breeding process on a commercial scale has never yet been achieved” (Fleming 2007:23). And, of course, nuclear power plants of any type entail enormous safety issues and create frightening new vulnerabilities. Further, one would think that those anthropologists who take an evolutionary perspective would have something to say about bequeathing to future generations toxic wastes with half-lives range from minutes to “about the same as the age of the earth: 4.5 billion years” (Fleming 2007:2).7

The most probably near future shift will be a great increase in the use of coal, directly or through liquefaction. This path obviously leads to great increases in CO2, and, inevitably, questions about for “peak coal” (see DiPeso 2009). Goodell (2006) documents the environmental, social, and political impact of the coal industry in the US – it is not a pretty picture. Whatever the mix of fossil fuels in the future, sustainability seems impossible:

And so we come to “renewable” energy sources: biofuel as a substitute for liquid petroleum fuels and electricity generated through wind, solar, hydro, geothermal, tidal and wave power. The problems of producing ethanol via industrial agriculture seem obvious to all but politicians:

Ethanol production using corn grain required 29% more fossil energy than the ethanol fuel produced (Pimentel and Patzak 2005:65).

If all of the croplands in the US were used to produce ethanol from corn, it would … displace less than half of 2008 US gasoline demand (Gorelick 2010:212).

The grain required to fill a 25-gallon SUV gas tank with ethanol would feed one person for a full year. (Brown 2006)

Simply put, producing biofuels on an industrial scale reduces available energy and reduces available food. Even if an impossibly large amount of acreage were dedicated to biofuels, the result would not come close to current needs, to say nothing of the ecological impact of such an effort, the corrosive nature of the product, etc. The picture is not much brighter with the other possibilities:

Heinberg (2005) goes through each potential source in some detail, and Bryce analyzes wind power and photovoltaic power generation in terms of power density, energy density, cost, and scale. Hydropower is a major source in several countries (China, Canada, Brazil, US, etc.) but is only available in limited areas. It does not appear that geothermal, tidal or wave power will ever meet a significant fraction of world needs. The major hopes lie with the generation of electricity through active solar and wind power. But these two turn out to be far more expensive and resource hungry than expected. At least with current technology, both photovoltaic and wind generation on an industrial scale are not replacements for a petroleum based technology as much as manifestations of it.

PV [photovoltaic] cells can’t be made without high-tech manufacturing facilities and energy-intensive materials, and according to some calculations, their net energy is right around 1-to-1…The net energy of PV cells, like most other renewable technologies, is radically asymmetric over time. Essentially all the energy inputs go into PV cells at the beginning, when they are manufactured and installed; the energy out put comes later on, and requires almost no further input. In effect, then, a PV cell can be seen as a way of storing energy…(Greer 2008:165-166).

None of which is to say that these technologies should not be pursued wherever they can produce a positive energy return. They are all under active development, and improvements in efficient will no doubt be realized. They may prove very handy in small scale application (mentioned below). But in the realistically foreseeable future, no combination of them will be able to sustain industrialized society.

Arthur C. Clarke

As every anthropology undergraduate knows, when the outside world with its industrialized wonders burst into peoples’ lives in New Guinea, the epistemological shock was enough to set a generation spinning off into cargoist fantasies. It is no wonder then that in the developed world, where there has been a relentless parade of such disjunctures within individual lifetimes (my mother was born 8 months after the Wright brothers’ first powered flight and died in early 2005, nearly 36 years after the first moon landing) there is a common belief that we will be saved from all our excesses by some new and wondrous technology. Current cargoist ideas include vision of neighborhood nuclear plants (Bethge 2010), laboratory produced oil (Squatriglia 2010 – one wonders what the net energy return is on that), and laser induced nuclear fusion power plants (Sutter 2010). For those who want to play God (or perhaps don’t know that there is something beyond themselves), there is “geoengineering” (O'Connell 2009, Madrigal 2010) which is just a magnification of the current IBM advertising campaign to “build a smarter planet.”8 Geoengineering, unfortunately, is not the ultimate conceit. The prize for that goes to “terraforming” Mars, the dream that we can infect Mars with terrestrial life and turn it into a blue and green home to be colonized by homo sapiens (presumably before we completely ‘marsiform’ Mother Earth). No doubt there will be technological wonders in the future, but we still have to deal with the legacy of the petroleum age.

James E. Lovelock (1994)

Throughout the 20th century anthropologists have conducted research within the context of the expanding global economic system. We have documented its rapid spread into the far corners of the world, and the frequently deleterious social and psychological results as communities found themselves being monetized and commoditized. While the discipline has struggled since the 1930s to conceptualize these processes, without much theoretical success in my opinion,9 we have mounted a telling critique of neoclassical economic theory, telling at least within departments of anthropology. Our substantivist objections to groundless models of human behavior have only influenced a few academic economists (I will mention one, John Gowdy, below). Ayres and Warr’s recent book The Economic Growth Engine: How Energy and Work Drive Material Prosperity(2009), attempts to integrate neoclassical economics with thermodynamics and evolutionary perspectives; addressed to professional economists, it is certainly a ray of hope. But outside the academy, in the business world, the neoclassical religion has never been stronger. Everywhere, it seems, people are clamoring to become more deeply involved in an economic system in which the goal of each component is to "grow" and the whole system of investment is premised on endless expansion through increased industrialization. The concern is with throughput without concern for the finiteness of the earth's ability to supply inputs or absorb outputs. We have reached the point where we face not only resource depletion (peak oil) but also levels of accumulated industrial waste which have pushed global climatic patterns past certain tipping points. While the public has become aware of "global warming," it is perhaps more accurate to speak of climate destabilization since the changes underway are complex and not fully understood. Several years ago the peak oil experts Anders Sivertsson, Kjell Aleklett, and Colin Campbell presented an analysis (Coghlan 2003) that concluded that global warming was not going to be a problem since industrial society would crash before then (cold comfort, literally and figuratively). Now we know that we face the worst of both possibilities: the climatic changes are already well underway and moving faster than even the experts thought just a few years ago. We are no longer in the Holocene but a new geological era, the “Anthropocene,” to use Paul Crutzen’s term10, in which human behavior, starting with James Watt's development of an effective, coal-fired steam engine, has changed climatic patterns. In her three part essay ""The Climate of Man" (2005)11 the science writer Elizabeth Kolbert quotes Robert Socolow, a professor of engineering:

The Green Revolution increased the energy flow to agriculture by an average of 50 times the energy input of traditional agriculture. In the most extreme cases, energy consumption by agriculture has increased 100 fold or more. (Pfeiffer 2004)

"The ... Green Revolution ... was a one-time miracle, and it's over. Since the beginning of the 1990s, crop yields have essentially stopped rising. [Meanwhile] The global population more than doubled in that time...

...at some point not too far down the road we reach the point of absolute food shortages, and rationing by price kicks in. In other words, grain prices soar, and the poorest start to starve. (Dyer 2006) [emphasis added]

The global food crisis seems to have caught the US by surprise in 2008, suddenly appearing in newspaper headlines and magazine cover stories. Of course there has been a long standing concern over the unsustainability of agribusiness. "In the United States, 400 gallons of oil equivalents are expended annually to feed each American" (Pfeiffer 2004). And that estimate is from 14 year old data. But rather than recite the details of mechanized farming and transcontinental and international food shipments, I will just focus on one dimension of the problem, one of the things they never told me about in my liberal arts undergraduate education or in anthropology graduate school: the Haber-Bosch process to produce fertilizer.

Here's the catch: the natural gas that fuels the process represents approximately 70% of the cost.

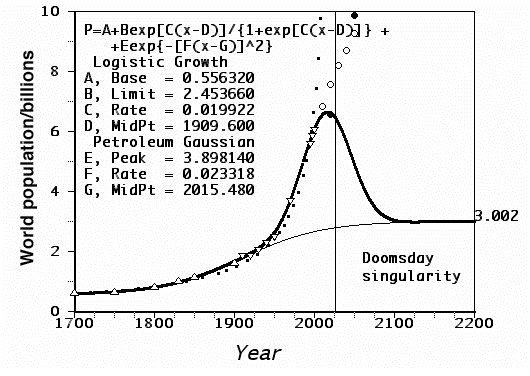

In 1960 Heinz Von Foerster and others published "the Doomsday paper" in which they fit a statistical model to population history and projected that if world population continued to grow as it had for the last 2,000 years, it would reach infinity on Friday the Thirteenth, November, 2026 (Von Foerster et al. 1960).

In 2000 Graham Zabel's paper, "Population and Energy," argued that "Energy is an issue that has been widely ignored when attempting to explain historical demography and it is widely ignored when attempting to project future demographic scenarios." Zabel attempted to break down population growth from 1700 to 2000 in terms of the estimated number of people supported by biomass, "traditional renewables (wood, dung, etc.) and animal power (with minor amounts of wind and hydropower)", by the use of coal, then the development of oil, and finally natural gas. The massive population increase attributed to chemical fertilizers seem to fall into his 'oil population' rather than his 'natural gas population', but the overall picture is clear enough.

When one considers peak oil, Zabel's analysis leads to an obvious and chilling conclusion:

Ferren MacIntyre recently published another projection testing hypotheses that took economic factors into account. One doesn't really need to master the details of his statistical analysis is understand the message of his summary graph:

As Heinberg and MacIntyre are aware, it is, of course, far too simple to assume that in large parts of the world agricultural productivity can go back to pre-industrial levels, as if there had been no loss of arable land to urbanization, no ecological degradation, no dislocation of agricultural populations, no loss of pre-industrial infrastructure or knowledge of farming, etc. It seems even the 'pessimists' are soft-pedaling their message.

The last few years have seen a torrent of articles, books and videos in North America, mostly by people outside academia, directly challenging the sustainable development model, and predicting the imminent end of suburbia and the American Dream (Greene 2007), industrial societies (Heinberg 2005), or worse:

Kumi Naidoo, the new Greenpeace head, says that human existence is "fundamentally under threat" (Jess 2009).

But as you will surmise, the real hotbed of this sort of thinking is the Internet.14

Perhaps the most provocatively named prediction is "The Olduvai Theory" found on the Web in a series of papers by Richard C. Duncan (1996, 2005-2006). He comes to the subject with a background as an electrical engineer. Duncan starts with assertion that "the life expectancy of industrial civilization is approximately 100 years: circa 1930-2030" (2005-2006:1). His measure of industrialization is worldwide energy production per capita or "e". Duncan argues the exponential growth of e ended in 1970, has basically flat-lined through 2008, and is about to go into sharp decline, with world population falling to about 2 billion by 2050 -- which would be a reduction of 4.6 billion people in the next 42 years. (For an alarmist reflection on the implications of these ideas see Arnett 2007).

An excellent web site, launched in 2003 and kept current, is "The Wolf at the Door: The Beginner's Guide to Peak Oil" (http://wolf.readinglitho.co.uk/ and http://www.wolfatthedoor.org.uk/) by Paul Thompson, a graphic designer in Reading, England (once again the non-academics are far ahead of us in educating the general public). Thompson pulls together a great deal of information; I wish here to draw attention only to his prediction of the imminent future, which he groups into "the four stages of the breakdown":

- Stage 1: Awareness: This is the stage we are at now...

- Stage 2: Transition: subdivided into two further phases:

- 2a: Ordered Transition

- 2b: Anarchic Transition

- Stage 3: Scavengery

... just about all hydrocarbons are unavailable. National security has disappeared, interdependence is unsustainable. We are forced to live in small groups of village or tribal size, growing our own food, maintaining our own buildings and providing our own security. Those who are not in village groups will be forced to steal from others.

This period is called Scavengery because we will be forced to rely on the remains of our present industrial society... Our societies will have to change dramatically with, for example, practices such as monogamy possibly giving way to polygam, and interdependence becoming multi-skilling. - Stage 4: Self-Sufficiency

... By now, everybody who is unable to convert to a sustainable, self-sufficient lifestyle would have died off, leaving only those in organised, independent groups to remain.…we might eventually 'progress' to something like a Medieval level of civilisation... [emphasis added]

There have been any number of post-apocalyptic novels and movies, and Duncan’s scheme can be seen as another intelligent, but amateur attempt to imagine the future. While anthropologists may find a list of these stages reminiscent of 19th century unilineal evolutionary schemes, Duncan does not, apparently, have an underlying social theory, or much background in non-European kinship systems (though, thankfully, he and others outside academia have not taken refuge in the just-so stories of evolutionary psychology).

Jared Diamond, professor of geography and physiology at UCLA, takes a far more sophisticated and deeply researched look at the world crisis in his recent book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (2005). While not specifically focused on prediction, the work, which has become a bestseller, reviews several specific cases of past and recent societal failures, and a few success stories, and seeks to identify the factors responsible for their various fates. Diamond has written a number of books and essays that speak directly to anthropological issues and are widely used in the US in anthropology courses. In the last section of the book, he tries to draw lessons from these cases, and ends, in sharp contrast to Duncan and Thompson, on a note of "cautious optimism." It received some initial rave reviews, for example:

My own opinion of the book is not nearly so positive. Diamond is to be commended for bringing awareness of the looming crisis to the general public. He takes the sort of broad comparative perspective that too few anthropologists are willing to attempt. But although the specific examples are recounted in very engaging ways, they involve interpretations of complex and controversial cases (e.g. the root causes of the Rwandan genocide) that were bound to raise objections. Smil (2008:2) dismissed it as “derivative, unpersuasive, and simplistically deterministic.” Within anthropology, My colleague Patricia McAnany was co-convener of a conference of archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, and historians who produced a volume taking issue not only with the factual details of many of the case studies Diamond cites but also with his 'methodological individualism'15 and the very concept of "collapse" as a model for the decline of state formations (Questioning Collapse: Human Resilience, Ecological Vulnerability, and the Aftermath of Empire, McAnany and Yoffee 2009). While the conference was considered significant enough to be reported in the New York Times (Johnson 2007), there is no doubt that Diamond's book will reach a much larger audience. Unfortunately I find Diamond’s closing arguments for optimism unconvincing, primarily because his overall analytical framework is seriously underdeveloped. Perhaps a sophisticated theory of social dynamics is too much to ask for from a non-anthropologist. Perhaps it is also too much to ask from an anthropologist as well, though there are others in academia willing to try.

One of the most popular scenarios in the face of these problems is the idea of sustainable development: “development which serves the needs of the present population without disadvantaging future populations” (Daily Tar Heel, 2010). While this may be realizable in a few small isolated areas, until we stop pumping oil, mining coal, cutting down forests, paving roads, and generating radioactive waste, the concept strikes me as a dangerously delusional fantasy.

Another whole dimension of the ‘sustainability problem’ that has recently come to wide public attention is our credit-based financial system. Our very currencies are premised on eternal expansion.16

The real ferment in modeling the future seems to be among those who see the standard indicators as headed downward. At issue is the abruptness of coming changes. In 2008 “The First International Conference on Socially Sustainable Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity”17 was held in Paris. “Degrowth” is an admittedly awkward translation of the French term décroissance.18 The analysis of the global situation is familiar:

If we do not respond to this situation by bringing global economic activity into line with the capacity of our ecosystems, and redistributing wealth and income globally so that they meet our societal needs, the result will be a process of involuntary and uncontrolled economic decline or collapse, with potentially serious social impacts, especially for the most disadvantaged.

The alternative goal bring proposed is sustainable degrowth, "reducing the ecological impact of the global economy to a sustainable level, equitably distributed between nations". I think the conference participants are quite right in recognizing that this “will not be achieved by involuntary economic contraction”. But the paradigm shift they call for, “from the general and unlimited pursuit of economic growth to a concept of ‘right-sizing’ the global and national economies”, however laudable, strikes me as even more utopian than visions of sustained development, and quite beyond any precedent in ethnography, history, or religious studies.

In contrast, John Michael Greer, in his book The Long Descent: A User's Guide to the End of the Industrial Age, (2008) presents the model of catabolic collapse (a term borrowed from biology referring to the breakdown of complex structures into constituent subunits). Rather than a sudden, total collapse, Greer predicts a prolonged series of step-downs specific to local and regional circumstances. This is quite similar to the future envisioned by Thomas Homer-Dixon in The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization (2008). Both authors stress that the breakdown of existing structures also means the generation of new opportunities and creative possibilities.

Representative of the most alarming scenarios is the recent paper “Tipping Point: Near-Term Systemic Implications of a Peak in Global Oil Production -- An Outline Review” by David Korowicz (2010). The theoretical approach is that of complex dynamics systems theory (most directly from Scheffer 2009). Although I can only claim a beginner’s knowledge of the theory behind his analysis, Korowicz’s “outline” of over 20,000 words is also the best grounded and most persuasive assessment I have come across (Korowicz is a physicist by training). A few passages will suffice:We are embedded within economic and social systems whose operation we require for our immediate welfare. But those systems are too interconnected and too complex to comprehend, control and manage in any systemic way that would allow a controlled contraction while still maintaining our welfare. There is no possible path to sustainability or planned de-growth. (7)

The challenge is not about how we introduce energy infrastructure to maintain the viability of the systems we depend upon, rather it is how we deal with the consequences of not having the energy and other resources to maintain those same systems. Appeals towards localism, transition initiatives, organic food and renewable energy production, however laudable and necessary, are totally out of scale to what is approaching. (4) [emphasis added]

Surely nothing could be of more central concern to anthropology than this global crisis. I do not know any anthropologist who is not deeply concerned; many are alarmed. ‘Global Warming’ is now widely recognized by the UN and national governments, the oil crisis is increasingly acknowledged, and the global food crisis is widely discussed, albeit as a short term problem. The full implications of the energy crisis for the long term food supply and world population levels have still not penetrated the mainstream media or general public discourse. There are some attempts to get the natural scientists who are modeling global patterns to involve social science findings in their projections; my colleague Carole Crumley has spent many years fighting this good fight, urging the necessity of including the human dimension in their analyses, with limited success (e.g. Hornborg and Crumley, 2006)19. Needless to say, most natural scientists do not know how to make use of anthropological studies that lack quantified data. And so the vast majority of those discussing the possible futures of humanity are natural scientists, or independent authors, or journalists, discussed above.

Any discussion of anthropological theorizing about energy and human societies must start, I suppose, with Leslie White and his famous dictum:

No doubt most social anthropologists take offense at White's 'superorganic' view of culture since it violates our sense of the importance of individual free will. Nor does his monolithic view of culture sit well with the traditional anthropological concern with diversity and specificity of cultural patterns. Most of us, having been profoundly affected by the personal relationships we formed during fieldwork, resist the idea that our findings are just another data point on a dimension of energy use. My own reaction to reading White is to wonder how anyone could have been so right and so wrong at the same time. White's scheme is extremely effective for organizing the long sweep of human history and energy levels are critical to social forms (so too are ecological factors influencing population densities, modes of communication, cultural traditions, etc.). Among those of us willing to speak in terms of cultural evolution (and I recognize that many are not), I think most of us would object strongly to his definition of cultural evolution in terms of per capita energy use.

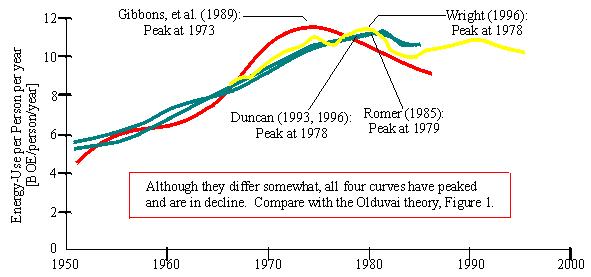

White, of course, was writing at a time when the finite nature of world supplies was not pressing. For contemporary readers this leads to uneasiness with the expansionist or triumphalist undertones of his scheme. When per capita energy use starts declining, as the following chart suggests it already has, are those societies which have been using energy at a higher rate still going to appear to have been "more advanced in an evolutionary sense" and will they still find themselves at "an advantage over other societies"?

World Average Energy-Use Per Person Comparison of Four Sets of Historic Data

("BOE" means Barrels of Oil Equivalent) [Duncan (1996)]

A much more pointed essay, "Energy and Human Evolution," by the anthropologist David Price20 was published in 1995. On the Internet, at least, it has achieved the status of a classic, widely cited and echoed on many web sites. The argument is both theoretically eloquent and extremely pessimistic.

Price starts with the Second Law of Thermodynamics:

Humans have increasingly been tapping into the energy stored up in the earth. This leads Price to a striking metaphor that has been widely quoted:

To Price, the human ability to cash in the world's energy stores has, in effect, made us an introduced species on our own planet:

And like introduced species, we are destined for runaway population growth, resource depletion, and population crash, in a word a classic overshoot (Catton 1982). Price continues,

The human species may be seen as having evolved in the service of entropy, and it cannot be expected to outlast the dense accumulations of energy that have helped define its niche. Human beings like to believe they are in control of their destiny, but when the history of life on Earth is seen in perspective, the evolution of Homo sapiens is merely a transient episode that acts to redress the planet's energy balance.

A more recent paper coming to a perhaps more optimistic interpretation of the impending collapse is "Production Theory and Peak Oil: Collapse or Sustainability?" by John Gowdy22 (2006).

One of Diamond's main points in Collapse is that communities who failed (e.g. the Norse in Greenland, Easter Island) had clung to dysfunctional cultural patterns rather than change them adaptively. Whether or not this is a valid analysis of what happened in either case is hotly contested, but the most general goal of systems is to persist, and a common reason for failure is inflexibility or lack of resilience. Gowdy addresses the question of existing institutions in the industrialized world and predicts an organizational refusal to adapt, writ large:

Gowdy's conclusion is only comfort for those who can take a very long view, and look past what must happen between now and then:

Finally, I would like to conclude this review of the literature with a recent challenge to anthropologists to address the energy crisis directly. Thomas Love, Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Studies at Linfield College, Oregon, made the case in a guest editorial, "Anthropology and the fossil fuel era" in the April issue of Anthropology Today (Love 2008) Love contends that "we are in the last days of cheap oil" and, following Price, asserts that "[h]umanity is already in ecological overshoot." Rather than lament the species' long-term prospects, Love clearly feels that anthropology can contribute useful information, and that such information will be used, in ameliorating the effects of the energy crisis:

Love call on us to focus our research on the current crisis:

I agree wholeheartedly with the concluding sentence of Thomas Love's editorial: "Let us examine the real crises upon us." But why is it even necessary for someone to say that? Why don't we have at least half the energy of most of the departments of anthropology in the world debating the validity of these warnings and what courses of action to pursue? Why are there literally only a handful of articles by anthropologists that address these problems?

An answer that has been suggested by many is that the idea of industrial collapse or a population die off is too dire to think about in a concerted way. While there may be some truth to that (as an American I cannot deny the existence of widespread denial), I think there are more specific aspects of current anthropology that explain the discipline's near silence.

The question of relevance has been a chronic concern for anthropology. Here is just one example from hundreds: "Do anthropologists have anything useful or relevant to say about human rights? Six Perspectives" (Anthropology News, April 2006). And the American Anthropological Association’s web page carries an announcement for a "Pulse of the Planet" Op-Ed series (http://www.aaanet.org/meetings/Pulse-of-the-Planet.cfm).

From global climate change and the human rights disasters that accompany violent storms and droughts to the increasing assaults on biodiversity and cultural diversity in the name of economic, energy, food, and national “security,” the “Pulse of the Planet” op-ed series takes a probing look at the ulcerating conditions that may be driving up the planetary pulse and asks the question: Where are we going, and at what price? Collectively, these anthropologists urge our leaders to rethink the meaning of security and the role of government in achieving a sustainable and healthy way of life.

Most of the time we are thus urging leaders to listen to us. But sometimes we are embarrassed by the fact that some parts of the power structure, in particular the military and intelligence community find anthropology's local knowledge and intensive field methods very relevant. How many of us, upon returning from foreign fieldwork, have received that phone call or inquiry from some innocuous government agency wanting to “exchange information”?

A few anthropologists (the leading figure is discussed below) are now "embedded" in Afghanistan and Iraq, and there has been much heated discussion of this situation. Many fear their local knowledge will be co-opted and misused. The American Anthropological Association appointed a commission on the "Engagement of Anthropology with the US Security and Intelligence Communities." The final report sought a rather lonely apolitical middle ground:

The Commission recognizes both opportunities and risks to those anthropologists choosing to engage with the work of the military, security and intelligence arenas. We do not recommend non-engagement, but instead emphasize differences in kinds of engagement and accompanying ethical considerations. We advise careful analysis of specific roles, activities, and institutional contexts of engagement in order to ascertain ethical consequences.... (Peacock et al. 2007:4).

At least one anthropology department, California State University – Long Beach, has formally debated the ethical implications of anthropologists' engagement with military and intelligence agencies (Loewe and Kelly 2008).

While the anthropological understanding of self and other, culture and society, seem profound on the individual level to us (and we hope, to our students), the utility of this empirical knowledge on a social level has probably been much less than claimed. I think the bitter truth in the characterization of earlier anthropology as 'the handmaiden of colonialism' is that the role was that of a servant, not a full participant. Anthropology may or may not have been a particularly handy handmaiden, but it was not a significant policymaker. While we have been worrying about relevance, with its implications of understanding and policy making, the real policy makers considered (and still consider) the utility of anthropological information in carrying out their plans. This, of course, rankles.

From its emergence, ethnography has prided itself in, and promoted itself to the general public on the basis of, the reflective value of the knowledge we have gathered about human communities around the world; what the study of ‘others’ tells us about ‘ourselves.’

The quality of our information about the variety of human societies and the conceptual foundations of the discipline coevolved with a methodology based on highly localized, in-depth long-term research. The central concept that developed was culture as socially learned, largely symbolically transmitted systems of action, meaning and value. Social anthropology is thus ultimately rooted, not in objective knowledge, but the appreciation of shared understandings, not just in external reality but in collusions about the meaning of aspects of external reality. Within the discipline the result is very understandably a concern with the reflexive nature of our knowledge, an appreciation that what we have learned is inseparable from how we have learned it, and that our knowledge, in its formation and dissemination, is not independent from those who are its immediate subjects. But there is a difference between self-awareness and self-absorption. Feeling, somehow, that we possess an exquisitely sensitive understanding of cultural meanings and their variations (why else did I suffer through fieldwork?) we doubt if non-anthropologists really 'get it.' The simple answer, I think, is that they don't worry about it.

Twenty years ago, Philip Salzman wrote a brief, rather cutting, reflection on the state of anthropological theory in North America, entitled "Fads and Fashions in Anthropology" for the AAA Anthropology Newsletter (Salzman 1988). When he completed his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in 1968:

As it happened, Phil and I overlapped in graduate school, and I find great resonance in what he says, including his self-deprecating comment about our naïve dismissal of structural-functionalism.23 To Salzman's surprise a few years later "the processualism of the earlier false dawn was characterized as the bad old anthropology, worth nothing and destined for the trash heap of false doctrines" (32)

Reviewing the twenty years since his Ph.D., Salzman finds that North American anthropology has followed a five year pattern of dismissing the past and adopting new intellectual fashions (largely, I might add from the fringes of the discipline, or beyond). Thus processual anthropology was eclipsed by structuralism (a turn that mystified me when I returned from two and a half years in the field in Kenya). Structuralism, then gave way to Marxist anthropology (having never been a structuralist, I did not feel that I could move downstream to 'post-structuralism'). Then "symbolic/semiotic/interpretive anthropology" held sway "taking 'text' to be any social/cultural phenomenon."

Salzman's article stops short of the post-modern wave, deconstructionism, and the rest. I presume my readers are familiar enough with the last couple decades. The bitter truth, I have long lamented, is that far from the development of cumulative knowledge or an appreciation of foundational works within the discipline, anthropology is, indeed, ruled by fashion.

Another voice decrying anthropology's turn to reflexivity comes from an unexpected quarter. Montgomery McFate24, the leading anthropological advisor to the Defense Department, traces the history of anthropology's associations with, and animosity toward, imperial power25 in "Anthropology and Counterinsurgency: The Strange Story of their Curious Relationship" (McFate 2005). McFate sketches the history of anthropology, particularly American anthropology in the 20th century, and laments "[t]he curious and conspicuous lack of anthropology in the national-security arena" and the "grave consequences" that have resulted.

In Britain the development and growth of anthropology was deeply connected to colonial administration. (28)

Once called “the handmaiden of colonialism,” anthropology has had a long, fruitful relationship with various elements of national power, which ended suddenly following the Vietnam War. The strange story of anthropology’s birth as a warfighting discipline, and its sudden plunge into the abyss of postmodernism, is intertwined with the US failure in Vietnam.(24) [emphasis added]

Part of the reason for this turn away from reality to seek a new intellectual fashion, as McFate sees it (and I suppose Salzman would agree on this particular point) is that "anthropology is primarily an academic discipline." But the real reason that anthropology, despite the value of our local knowledge gained through long-term in-depth fieldwork in "foreign cultures and societies ... is a marginal contributor to U.S. national-security policy" (28) is the profession’s reaction to the use of anthropologists in Viet Nam by the RAND Corporation, Project Camelot26 and the revelation that anthropologists were involved in U.S. counterinsurgency programs in Thailand.

Rather than face the real issues and contribute to them (as we should in McFate's opinion), Anthropology sought other muses:

The turn toward postmodernism within anthropology exacerbated the tendency toward self-flagellation, with the central goal being “the deconstruction of the centralized, logocentric master narratives of European culture.” This movement away from descriptive ethnography has produced some of the worst writing imaginable. (28)

DOD [the U.S. Department of Defense] yearns for cultural knowledge, but anthropologists en masse, bound by their own ethical code and sunk in a mire of postmodernism, are unlikely to contribute much of value to reshaping national security policy or practice.(37) [emphasis added]

The general conclusion I draw from such disparate critiques as Salzman’s and McFate’s is that, in Thomas Kuhn's terms, anthropology is in a "preparadigmatic state" that is we lack a generally agreed upon framework, a method of generating hypotheses, and definitions of what constitutes evidence, on which to start a predictive theory. We are still doing alchemy, not chemistry, or as Gregory Bateson characterized the behavioral sciences in 1971:

Just what role should anthropologists take? David Shankland, reflecting on the 2000 conference of the Association of Social Anthropologists in Britain, expressed his discomfort with the

This is certainly a standard and long-standing self-image, one that is the justification for a large proportion of non-academic jobs held by anthropologists (and an echo of undergraduate teaching). But Shankland reminds us that

The vast proportion of development is about universals in the human condition. In order to study this, we surely need to take into account the comparative dimension much more scrupulously and explicitly.

Shankland's call for a refocus on universals may seem desperately out-of-date to many, but the emphasis on the comparative approach, which we tout in our introductory texts, needs to be rethought, and not abandoned to those who do so quantitatively (they, at least, have explicitly wrestled with the fundamental issues of comparison, whatever you think of their results). Here, again, we hear the need to more fully actualize the realization that anthropology has long come to, that despite the location of classic case studies (the island of Kiriwina and Tikopia, the isolation of the Nuer in the Southern Sudan), and despite the premises of structural-functionalism, societies are not cleanly bounded units. Ironically Malinowski's first book was about inter-ethnic trade and its effects, not just intra-island social dynamics, and to read The Nuer and assume they dealt only with the culturally very similar Dinka misses the raison d'être of the book. There is a vast body of fascinating studies on ethnic boundaries and inter-ethnic cooperation and conflict that we need not forget.

Shankland deflates the idea that an anthropological understanding of cultural differences is necessary for "development" in its material form:

The example he chooses is probably the sort of thing that Montgomery McFate would want us to study (and report on):

With the death toll from the latest decades of ecological theft of the Congo estimated in the millions, the international arms trade is, indeed, serious and should not be underestimated. But if one takes a broad definition of the "instruments of health", then perhaps a far greater "triumphant, albeit perhaps ultimately tragic" aspect of rampant cross-cultural technology transfer has been death control. Certainly no one who was involved in the spread of new food crops from the new world (potatoes, corn), or the spread of soap, machine-made cotton clothing, basic biomedical care, etc, was intending to cause the explosion of world population which is now one of the fundamental drivers of the global crisis and the clearest manifestation of our overshoot. While there is much good work to be done by anthropologists translating concepts in order to facilitate the delivery of health care across cultural and linguistic boundaries, in my experience people in the 'developing world' do not need to be convinced of the power of biomedicine. The hospitals and clinics I am familiar with in Africa are overwhelmed with patients (and desperately short of personnel and supplies) because of the demographic "success" of the species. And to bring it all back home, Zabel reminds us

In 2000 Eugene Mendonsa wrote “What does anthropology have to offer in the solution of the world’s problems – Are we kidding ourselves?” Mendonsa noted that

While Mendonsa cannot accept rosy visions of future progress, and hopes for a just a bumpy transition toward a more ecologically sound economy -- rather than the collapse others predict -- he sees enduring strength in anthropology’s emphasis on ethnography, ecology, adaptation in an evolutionary perspective and, especially in these times, a focus on political economy.

Of course it is ludicrous for me to suggest what my fellow anthropologists can or should do. But here goes:

Let's start by dismissing the obvious temptation to study the peak oil movement and 'power down' groups as revitalization movements. It's been done, and by objectifying their social processes we will miss the content of their concerns and the effects of their actions.

Let's not try to do "social science" as if it were a version of natural science; it isn't and the natural scientists know it. If we are cultural brokers, then we need to assist the natural scientists in their efforts to inform the general public. To do so, we need to forget disciplinary boundaries and educate ourselves and our students as best we can in a number of fields beyond anthropology.

While we are at it, let's stop worrying about the reflexive nature of our knowledge. No one else worries about it, and it misleads us into involuted particularisms.

As discussed above, we need to return to a wider, comparative scale of analysis, and focus on the interrelationships between regions, classes, and other social divisions, particularly the role of energy and other resources in those exchanges. With apologies to Evans-Pritchard: Cherchez le hydrocarbure.

We need to be guided by a keen analysis of political economy, power structures and inequalities, one that is neither distracted by our own social myths (e.g. triumphant democracy) nor dismissive of the role of myth in action (my own preference for approaching how political power works in modern society is Peter Dale Scott's concept of "deep politics” [1996]).

It is easy to lose hope if we find ourselves working on the wrong scale. Korowicz is probably correct in saying that “Appeals towards localism, transition initiatives, organic food and renewable energy production, however laudable and necessary, are totally out of scale to what is approaching.” But there appear to be no central solutions on a global scale – we are all in for the ride. I have no illusion that a few enlightened anthropologists will alter the course of the petroleum empire. No doubt the closer one gets to centralized power the more the feedforward of massive institutions restricts choice. But there will always be choices on the human scale -- indeed as old structures fail choices increase.

Because of the current economic recession, millions upon millions of people in the industrialized world have already started reducing their energy consumption. Are they losers or pioneers? Those who do not see peak oil as a global crisis speak of recovery. Those who see super-historic changes on the way have no doubt that the collapse has already begun (e.g. Chossudovsky and Marshall 2010). Many are taking steps to adapt, and to preadapt to anticipated changes. Green politics are no longer marginal in many countries. All over the US "powerdown" groups have sprung up. Students are traveling around the globe to learn methods of organic and alternate farming. Greer (2008:160) points out that thanks to the age of the automobile there are half a billion alternators in the US that could be used for homemade electricity. Indeed, William Kamkbwanba of Malawi is currently the poster child for such efforts, having rigged up a handmade windmill and alternator and electrified his house at the age of 14 (http://www.ted.com/talks/william_kamkwamba_how_i_harnessed_the_wind.html).

Mike Ruppert is setting up CollapseNet (http://www.collapsenet.com/) "to promote the rapid and focused sharing of information between millions around the world who are preparing for the collapse of human industrial civilization". ‘Do it yourself’ takes on a whole new depth of meaning if larger networks fail.

Is this wisdom or foolishness? There is so much uncertainty in our future that I do not think one can tell -- it is all an open question (and hopefully "open" is the operative word here). From an evolutionary perspective the rule is 'when in doubt, diversify." I firmly believe in the value of knowledge and insights, including those gained through the ethnographic encounter and anthropological reflections. I also firmly believe that any such knowledge is partial, and embedded in the particular.

But however ambiguous the methods by which it is derived, anthropological knowledge, far from being arcane, is directly relevant. Anthropologists know that the majority of our species lives fulfilling lives without constantly seeking new material acquisitions. Anthropologists know that mass media are not needed to fill one's experience with art and creativity. While the EuroAmerican perspective worshiped individualism and believed 'the social contract" was holding down our inherent savagery, Fortes and Colson and Evans-Pritchard and many others explained ways in which uncentralized societies maintained law and order (at far lower cost to life and limb than our own). Granted millions will not suddenly take up reading Fortes, but we should not abandon the public to "Mad Max" and the absolute slew of hyperviolent dystopian futures of current Hollywood fantasy. We know better, and that knowledge is a tool that needs to be shared.

It is on the ethnographic, individual, family, community network level that we can grasp both the beliefs that mold and drive our actions and also our imperfections. It is on this level that we can talk about the generation of morality, a dimension of life which so many of those who are looking at the global problems see lacking in current attempts to keep industrialization expanding.

We need not to lose heart from visions, such as Price's, that question the survivability of the entire species. His analysis, while chillingly convincing in the overall argument, does not take into account the most striking aspect of the human species, the diversity of our adaptations. Cultural ecology is not simply biological ecology. Unlike his examples of species which have overshot their resource base (yeast in grape juice and reindeer introduced on an island), we are not homogeneous. However and whenever the world population experiences the ‘down slope’ it will be experienced diversely. The age of oil has been brief, within living memory in many parts of the world, while the traditional focus of ethnography has been on hard-won, deeply rooted ideas of how to live (many years ago I gave an undergraduate seminar on “Ecological Awareness in Non-Western Societies” and managed to get most of the class to understand what I was driving at by the end of the semester). In taking a wider comparative view, we need to resist the seduction of unitary global models from the world of numbers.

Finally, let’s remember that not all humans, as yet, are dependent on fossil fuel for their subsistence. The relatively remote populations in Africa or New Guinea might well survive even a cataclysmic collapse of urban civilization, industrial production, and agribusiness. Perhaps all those obscure anthropological field trips will pay off. While James Lovelock suggests, in The Revenge of Gaia (2006), that we start stockpiling the arctic, the last green place in our future, with how-to-do-it books on acid free paper, we anthropologists have been collecting indigenous information in the form of Australian songlines describing the details of their environments,, the chant the Trobriand wood carver makes as he forms the prow board of a deep water canoe, and thousands of pieces of African social wisdom. And as we all know, these are ways to be human that are as valuable as those that will necessarily disappear.

If faut cultiver nôtre jardin.

http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-the-haber-bosch-process.htm

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0406/feature5/

http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article25306.htm

http://www.oilcrash.com/articles/arnett05.htm

http://petrole.blog.lemonde.fr/2010/03/25/washington-considers-a-decline-of-world-oil-production-as-of-2011/